Ardor (34 page)

Authors: Roberto Calasso

Tags: #Literary Collections, #Essays, #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural

XII

GODS WHO OFFER LIBATIONS

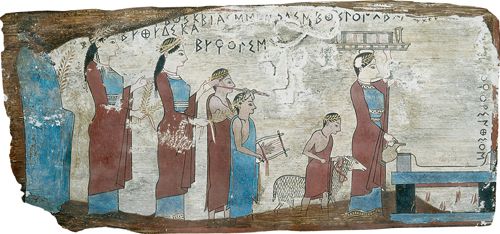

There is one gesture that inextricably unites the whole Indo-European world. It is the gesture of the libation. The pouring of a liquid into a fire that flares up, destroying a valuable or an ordinary substance in the flame. Libation is found back in the Minoan period, on the Hagia Triada sarcophagus. Homer’s characters often carry it out as a necessary preliminary to their exploits. Sacrifices performed with no libation are extremely rare. And even Olympian gods are depicted on many vases in the act of offering a libation. Erika Simon has studied them—and has asked the inevitable question: to whom are they offering the libation? And why do gods feel they have to do it, just as much as humans?

In India, libation is to be found everywhere. The brahmin has to perform it each morning before sunrise, and each evening before dusk. It is the simplest rite, the

agnihotra

, which lasts about a quarter of an hour. Hundreds of times a year, thousands and thousands of times throughout a lifetime. But in the description given in the Br

ā

hma

ṇ

as, even the smallest rite is broken down into almost a hundred acts. And the texts tirelessly reiterate that this rite encapsulates all the others, and they describe it as the

arrowhead

of all rites: “What the arrowhead is to the arrow, the

agnihotra

is to the other sacrifices. For where the arrowhead flies, there flies the whole arrow: and so all the works of his sacrifice are released, thanks to this

agnihotra

, from that death.”

It is not a social rite. The head of every family performs it alone. He needs no officiants, his consort is not present. Violence—which always leaves some mark, however much one tries to hide it—is absent here. But destruction is present, the irreversible yielding of something to an invisible presence. This action of abandoning something is called

ty

ā

ga

—and is often presented as the essence of sacrifice, of every sacrifice. Or otherwise: as its prerequisite. It is the gesture that indicates someone is approaching an invisible presence—showing submission or at least the willingness to

give way.

Marcel Granet, in

Danses et légendes de la Chine ancienne

, a work in which his genius shines, defined the virtue of

jang

, which is indispensable to the Son of Heaven, who wants to maintain his sovereignty, as a

yielding in order to get

, where it is essential that the gesture of yielding comes before everything else.

* * *

Libation: the act of pouring a liquid into the fire or onto the ground. Pure loss. Irreversibility. The gesture that most resembles the flow of time. The perfunctory Latins had only one word for it:

libatio.

The Greeks—three subtly different words:

cho

ḗ

,

spond

ḗ

, and the verb

leíb

ō

.

Spond

ḗ

was the only way, in Greek, of saying “truce” or “peace treaty.” At the start of the Olympic games, heralds ran through Greece shouting:

“Spond

ḗ

! Spond

ḗ

!”

All fighting would then stop. The Vedic people used fourteen terms to describe a particular type of libation,

graha

, in a particular type of liturgy: the

soma

sacrifice. But only for the morning libations. Another five names were needed for those at midday. And five more for those in the evening. And yet they said there was no simpler, more straightforward act for showing the sacrificial attitude. “The murmured prayer is a covert form of sacrifice, the libation is an overt form,” we read in the

Ś

atapatha Br

ā

hma

ṇ

a.

For the prayer is murmured, while the act of pouring liquid cannot be hidden. Vedic men performed this act every morning, every evening. But so did the Greeks, according to Hesiod, who recommended the offering of libations “when you go to bed and when the sacred light returns.” The Vedic people built a huge edifice of other ritual acts around this single act—and catalogued them in vast commentaries. The Greeks included it in their daily lives and in their rituals without any theorizing. Homer very often speaks about libations, since they formed part of the events he was describing. Their significance was implicit. The libation, as well as being the simplest form of worship, was also the oldest, if we are to believe Ovid. Water had been poured before blood:

“Hic qui nunc aperit percussi viscere tauri

/

in sacris nullum culter habebat opus.”

“The knife that today opens up the entrails of the slaughtered bull / played no role in the sacrifices.” And, once again according to Ovid, the libation came from India. Dionysus, or Liber, had introduced it on his return from his eastern expeditions:

“Ante tuos ortus arae sine honore fuerunt

, /

Liber, et in gelidis herba reperta focis.”

“Before your birth the altars were without offerings, / O Liber, and grass grew on their cold hearths.” But Dionysus, “having conquered the Ganges and the whole Orient,” was said to have taught the offering of cinnamon, incense, and other

libamina.

From Liber also the name

libatio.

Through him the Vedic doctrine of sacrifice became meshed with that of the Romans.

* * *

Libation: the unrenounceable gesture of renouncement. Never so harrowing as the moment when we see Antigone before her dead brother, and “right away she lifted up with her hands the dry dust and a well-wrought bronze bowl to sprinkle on the corpse a triple libation.” There is no need for fresh water—nor is it necessary to pour Oriental perfumes. Even the “dry dust” sprinkled by Antigone is just as good for a “triple libation.” And the hopeless incongruity between that “dry dust” and the “well-wrought bronze bowl” that Antigone uses to pay homage to her brother goes back to the very origin of the gesture, which is the simple celebration of something that is forever lost.

* * *

The gods were great experts in the art of lengthening and shortening the rites. For the rite, like poetry, is greatly extendable or contractable. After having celebrated a

sattra

that lasted a thousand years, Praj

ā

pati and the gods knew perfectly well that humans would be incapable of following them. Too weak, too incompetent. The gods said to themselves: “We have brought this [sacrifice] to an end with our divine, immortal bodies. Mortals will never be able to complete this. Let us try then to contract this sacrifice.” And so the thousand-year

sattra

became the

gav

ā

mayana

, the “march of the cows,” which is still a

sattra

, but lasts only a year. But it could not be supposed, even then, that all people would spend a whole year on that rite. So the gods set about reducing it further and further. Until there were rites that lasted only three days, or two days—or just a few hours. And finally they arrived at the two

agnihotras

, for the morning and the evening. This was the nucleus that could be split no further. The rite consisted of pouring milk on the fire. Nothing could be simpler—even if the gesture was linked to dozens and dozens of others. Before this rite, below this rite there could be nothing more than formless life. Yet into those few minutes was concentrated the thousand-year

sattra

of the gods. “Therefore the

agnihotra

is unsurpassed. Undaunted is he who knows thus … therefore this

agnihotra

is unlimited.”

* * *

Each morning and each evening, just before sunrise and again before the appearance of the first star, the head of the family pours four spoonfuls of milk into a larger spoon and then pours it into the fire, twice. All forms of worship emanate from this gesture, carried out by a single person, using the most ordinary of substances, with no need for the help of priests. And it is something that has no beginning and no end, since there would be endless arguments if anyone tried to establish that the morning libation or the evening libation had priority. One relates to the other, in a perpetual cycle. Nothing comes as close to the continuity of life. And so, “as hungry children press close to their mother, so do living beings around the

agnihotra.

” The simplicity of this rite can only stir the boldest speculations around it. And, above all, the “limitless” nature of those gestures reassures those who perform them as to the limitlessness of their own being, however plain and simple such display might seem: “And in truth he who knows the limitlessness of the

agnihotra

, in this way is himself born limitless in prosperity and progeny.”

The

agnihotra

is the occasion for making the distinctions on which all the rest will be built. The libation, however simple, will never be one alone, but double. Why? Because one does not exist. Even in the very beginning, there were always two beings: Mind and Speech, Manas and Vāc. Mind and Speech almost entirely overlap and allow themselves to be treated as “equals (

sam

ā

na

).” And yet they are “different (

n

ā

n

ā

).” When they become involved in the rite, both characters are to be remembered: so each of the libations appears as a replica of the other, yet at the same time they are different, since they are still two, and therefore with one preceding the other. And thus the relationship between two powers begins to take form. When Mind and Speech then free themselves from each other—as happens at the very moment in which the libation is repeated—it sets off the whole series of dualities with which we have to deal. And reproduced in each will be that tension between limitless and limited that already exists in the relationship between Praj

ā

pati and the gods.

* * *

“For whichever divinity a person draws this libation, that divinity, being seized by this libation, fulfils the wish for which he draws it.” This sentence appears in the passage that most clearly expresses the acrobatic play on the word

graha

throughout the

Ś

atapatha Br

ā

hma

ṇ

a.

Usually translatable as “libation,”

graha

is always related to the verb

grah-

, “to grasp”—in a similar way as the German word

begreifen

, “comprehend” (from which

Begriff

, “concept”), is related to

greifen

, “grasp.” A further difficulty arises with the continuous alternation, in the word, of the active and passive meaning:

graha

can be the one who grasps and the one who is grasped, what draws the libation and what is drawn by it. At this point Eggeling explained in a note: “The whole Br

ā

hma

ṇ

a is a play on the word

graha

, in its active and passive meanings of grasper, holder, influence; and draught, libation.”

The libation is a way of grasping (of understanding) the divinity. And from it the divinity feels bound, grasped. This also happens with names: they are our libations to reality. They are used to grasp it: “The

graha

is in truth the name, for everything is grasped by a name. Why wonder, then, if the name is

graha

? We know the name of many, and is it not perhaps with the name that they are grasped for us?”

* * *

A crucial equivalence is that between Sun—“that one burning yonder”—and Death. Not only can the source of energy be a cause of death, but it is death itself. This is why the relationship between S

ū

rya and his bride Sara

ṇ

y

ū

bears so many similarities to that of Hades and Persephone: for the

ṛṣ

is

did not regard Hades as the one who rules over the shades but the one who streaks the sky and spreads light. Yama, ruler of the dead, would be just a son of his—a consequence of his being, which itself is already Death.