Around the World Submerged (43 page)

Read Around the World Submerged Online

Authors: Edward L. Beach

One man, however, was not affected by any of this protocol; Franklin Caldwell had been expecting a babygram, but none had arrived for him. In vain, he had haunted our radio room those last few days under way, and in vain, he had searched the smiling faces on the dock for that of his wife. She was not to be seen, and when he finally got ashore and to a telephone, it developed that she had one of the best excuses in the world for not being present to welcome her husband. Once informed of the situation, Will had Caldwell off the ship and, legitimate trip or not, into an official car within minutes. An hour or so later, a baby girl named Sandra swelled

Triton

’s dependent population by one.

With all the goings on, it was quite a while before I was able to have that quiet communion with my own wife and family which is the traditionally most cherished reward for the sailor home from a long voyage. There were a hundred things to talk to her and the children about, and a number which had to wait until the youngsters had said their prayers and gone to sleep.

“Sounds to me,” I said, when we were at last alone, “that you make out better when I’m not here than when I am.”

Ingrid sighed and put her head on my shoulder. “You’d

better not put me to another test for a while,” she said. “The children kept me pretty busy, and I got quite a few calls toward the end from some of die wives who were getting rather anxious. . . . The worst time was when Admiral Rickover called on the telephone.”

“What’s this?” I asked. “Nobody told me about that.”

“Well, I’ve not had a chance to until now, sweetie. I had a party for all the officers’ wives, and right in the middle of it the phone rang. It was long distance. So I said yes, this was Mrs. Beach on the phone, and then a voice said, This is Admiral Rickover. I want you to know privately that your husband is all right. Everything is fine. Don’t worry about him.’

“I must have let out a yelp or something, and I said, ‘That’s wonderful!’ and I could hear all the conversation in the living room suddenly stop dead. Everybody was listening, and everybody was hoping it was some kind of news about the ship.

“I thanked the Admiral, and he said good-bye and hung up. Then I remembered that in the past you had cautioned me against passing on information from calls such as this, and I had missed my chance to ask the Admiral if it was all right to tell the other wives. You said I could never know what might be behind the call, so I was never to let anyone even know that I

had

been called.

“There wasn’t a word I could say, but still I had to go back into the living room and face all those girls. They all just looked at me, and I thought fast and said, ‘That was my father’s doctor calling from Washington, where he’s had to come from California for a meeting, and he said that Father has been much better recently.’ I really felt terrible, lying to them like that. They all looked so dreadfully disappointed, and I wanted so much to tell them.”

I hugged her. “Good girl,” I said. “It was a lot tougher on you than on them. Anything else happen?”

She chuckled. “You had said that you didn’t know when you’d be able to get mail, so I didn’t write this time, except a little while ago, when I thought maybe I should have at least one letter in the mail for you just in case—did you get it, by the way?”

I shook my head.

“Well, I suppose it will catch up to you here at home. Anyway, one of your crew didn’t get the word to his wife. A couple of weeks ago, this girl called up, and she was nearly in tears. She had written seventeen letters to her husband, and he hadn’t answered a single one!”

“Why did she call you?” I asked. “We had put out the dope that anyone with a problem should call up the Squadron. . . .”

“I’m glad she did, of course,” Ingrid interrupted. “Women understand these things better than men do. She knew I couldn’t write the letters for her husband. All she wanted was some womanly comfort. Besides, I told them all to call up if they felt like it.”

“You what? How did you do that?”

Ingrid smiled. “I forgot that my letter never reached you. It tells about it. I gave a coffee for all of them—it was a lovely warm day, and we had it outside, and that’s when I told them. Mrs. Poole came, too, and she never said a word about her husband being home.”

“You had 183 women, here?” My voice must have had an incredulous tinge.

“All your crew isn’t married, silly! Besides, some couldn’t come. But the garden is big enough, and all the officers’ wives helped.”

Ingrid sighed again. “They were all extremely nice. The only bad time was just before they came, when the telephone operator got me all excited about a long-distance call coming in, and I waited around thinking it must be about your arrival

at last. But when the call finally came through, it was just a polite girl’s voice saying she was sorry she couldn’t come.”

We had been home for two days, when all at once I had occasion to recall the intuitive warning I had ignored when we designed and ordered our commemorative plaque. Lieutenant John Laboon, Chaplain Corps—a 1943 Naval Academy graduate who had resigned to enter the Jesuit priesthood after the war and had subsequently re-entered the Service as a Chaplain—was responsible. This onetime All-American lacrosse player and decorated submarine combat veteran, now the Catholic Chaplain for our nuclear submarine unit in New London, had come aboard to see if there were anything he could do for us. Over a cup of coffee, he confessed that although he could translate most of the words in our plaque’s Latin inscription, one of them was too much for him.

“What word?” I asked, my stomach experiencing a precipitant sinking feeling.

“Sactum,”

said Laboon. “If it were

‘Factum,’

now, the phrase would literally mean ‘It is again a fact.’ But I don’t know the word

‘Sactum.’ ”

Hasty investigation restored Father Laboon’s faith in his preordainment schooling. There simply was no such word as

“Sactum”!

It turned out that in receiving and reading back the Latin inscription over the telephone, the letter “F” in the word

“Factum”

had been erroneously taken down as “S,” and the plaque as delivered to the US ambassador had therefore contained a misspelled word!

The hopelessness of the situation was enough to make one despair, but there was one thing we could do: we could get a new plaque—with the word “F

ACTUM

” spelled correctly—over to Spain immediately; even though the original one might have contained an error, at least all posterity would not have the opportunity to criticize America’s lack of erudition.

So ran my thoughts on that black Friday, the thirteenth of

May, as

Triton

went to work. A new plaque was cast forthwith. It was still cooling as final arrangements were made with a trans-Atlantic airline. In the meantime, I placed a telephone call to the Naval Attaché in Madrid, to insure that the situation would be properly taken care of in Spain.

By Sunday morning the plaque was ready and packaged. Jim Hay took it by automobile directly to New York’s Idlewild Airport, where it was delivered into the hands of the pilot of a TWA plane bound for Boston and thence Madrid, nonstop. At 8:00

A.M

., Monday morning, the jet rolled to a stop at the Madrid airport and was met by a US naval officer who took custody of the weighty package; and in due course the replacement was made and the mistake rectified insofar as it lay in our power.

The correct plaque is now mounted on the wall of the city hall of Sanlúcar de Barrameda, the port city near the mouth of the Guadalquivir River from which Magellan left on his historical voyage. Beneath it is a marble slab, installed by the Spanish government, memorializing the fact that it had been brought by the United States submarine

Triton,

first to circumnavigate the world entirely submerged, in homage to the first man to circumnavigate the globe by any means. The plaque originally delivered, bearing the word

“Sactum”

instead of

“Factum,”

is now held by the Mystic Seaport Museum at Mystic, Connecticut. A copy from the same mold is mounted in the ship. Four others have been presented to the Naval Academy, the Naval Historical Association in Washington, D.C., the Submarine School in Groton, Connecticut, and the Submarine Library at Groton within arrow shot of the launching ways where the

Triton

first took the water.

For the next month or so I dreaded the receipt of mail, for the Log of our journey had been made public by the Navy Department, and, of course, our error was plain for anyone to see. But only one person, a woman Latin teacher, very courteously and tactfully wrote to point out the mistake.

There were, of course, several other loose ends to wrap up: Poole, thoroughly examined aboard the

Macon

and later at a hospital in Montevideo, needed no operation. His third attack, which had precipitated our decision to seek medical assistance, had been his last—even as he himself had predicted. He had had a pretty rough time from curious friends in New London, and to his credit had said nothing to anyone.

Our fathometer, when inspected, brought an embarrassed frown to the faces of

Triton

’s builders. The cables connecting its head, in our bulbous forefoot, to the receiver in our control room, had been laid in an unprotected conduit through our superstructure which by mischance was subjected to severe water turbulence when the ship made high speed. Exposed thus to constant buffeting from the water, one by one the cables had ruptured. This will never happen again.

The return of our hydro papers to the Navy Oceanographic Office (to give it its new title—our Navy is constantly changing the names of things) has been rather disappointing. Only a few of the 144 we launched have come back. Possibly their finders are keeping them, in their pretty orange bottles, as souvenirs of

Triton

’s voyage.

So far as Carbullido was concerned,

Triton

kept her promise. The problem was broached to Pan American Airways, and, aided and abetted by various company officials with a warm heart for the Navy, a magazine article about our cruise was sold for exactly the cost of a round-trip ticket to Guam. Carbullido got home on Christmas day, 1960, with sixty days’ leave in his pocket. His father had recently purchased a gasoline station; so the dutiful Carbullido spent his time on Guam pouring gasoline into the gas tanks of automobiles.

The concern I had about the young man who saw our periscope in Magellan Bay is still not completely dissipated. There were no repercussions from the Philippines awaiting us in New London, but after a few months the National Geographic Society believed our friend in the dugout canoe had been

located. His photo did not, however, greatly resemble the lad our photographic party snapped on the other side of the world, and his name was the same as that of the local Chief of the Constabulary. Rufino Baring, if it was indeed he, thought he had seen a sea serpent that day, and, in terror, had kept his entire encounter with us a secret.

Commander Will Adams has his own command, the brand-new

Plunger,

under construction at Mare Island, California, and I expect we shall hear more of her in due course. Les Kelly, also a Commander, has another year or so in command of

Skipjack.

As this is written, the only one of

Triton

’s circumnavigation wardroom still in the ship is Tom Thamm, now a Lieutenant Commander and no doubt destined to become the Old Man of the Ship, the oldest plank-owner, as I was of my long-dead

Trigger.

As these final words are written,

Triton

is again at sea, under a different Commanding Officer. In a few more months, she will no longer hold the title of being the world’s biggest submarine, for the first of the new and heavier Lafayette-class ballistic-missile submarines will soon be commissioned. But for a very long time to come,

Triton

will continue to serve our country to the best of her tremendous and versatile capability, wherever the need may arise. As is true with all naval vessels, she will have a succession of skippers, and a succession of different people will form her crew. Time will slowly erode her newness and freshness, and the diverse requirements of the national policy will send her hither and yon throughout the waters of the world, charting new courses or following courses charted by others, as the case may require.

The members of

Triton

’s crew who made the voyage with her are already largely dispersed to other assignments, many of them to other submarines. Some of them are, at this very moment, on patrol in ballistic-missile submarines, helping to safeguard America’s ideal of freedom and humanity. Some,

having served long and faithfully in the Navy and the Submarine Force, have retired to civilian life.

As time goes on, more and more of us will retire, but in future years, all of us, like myself—though perhaps no one so much as I—may have occasion from time to time to reflect upon the events of this first voyage of the

Triton.

As we do, we will no doubt find our accomplishment pale beside far greater deeds as yet unaccomplished on or beyond this earth. For as soon as the capability is there, man will do what needs to be done so that earth and the spirit of man will both benefit therefrom.

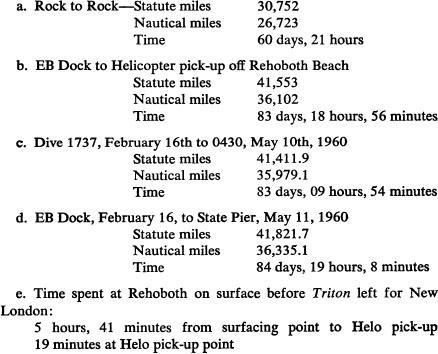

Data Sheet Appendix to First Submerged Circumnavigation Certificate

Exact mileage—nearest mile and nearest hours—(All “days” calculated on 24 hour basis) for: