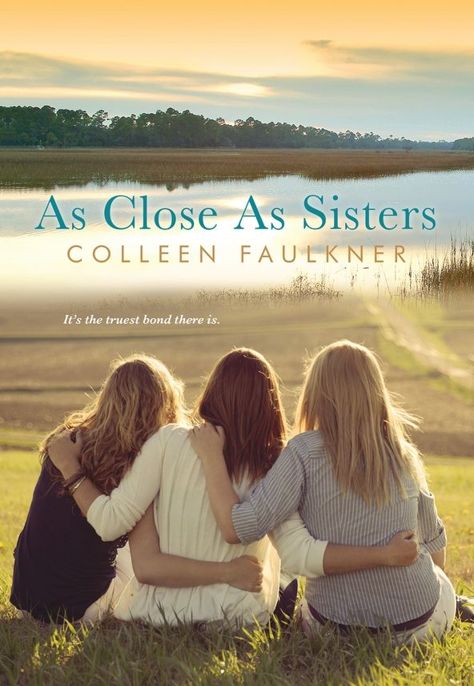

As Close as Sisters

Read As Close as Sisters Online

Authors: Colleen Faulkner

Tags: #Fiction, #Contemporary Women, #Family Life, #Literary

Books by Colleen Faulkner

JUST LIKE OTHER DAUGHTERS

AS CLOSE AS SISTERS

Published by Kensington Publishing Corporation

As Close as Sisters

COLLEEN FAULKNER

KENSINGTON BOOKS

www.kensingtonbooks.com

www.kensingtonbooks.com

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

Books by Colleen Faulkner

Title Page

Dedication

1 - McKenzie

2 - Aurora

3 - McKenzie

4 - Janine

5 - McKenzie

6 - Lilly

7 - McKenzie

8 - Aurora

9 - Janine

10 - McKenzie

11 - Janine

12 - Aurora

13 - Janine

14 - McKenzie

15 - Lilly

16 - McKenzie

17 - Aurora

18 - McKenzie

19 - Aurora

20 - Lilly

21 - McKenzie

22 - Janine

23 - Aurora

24 - Janine

25 - Aurora

26 - Lilly

27 - McKenzie

28 - Lilly

29 - Janine

30 - Aurora

31 - McKenzie

32 - Janine

33 - McKenzie

34 - Janine

35 - McKenzie

36 - Aurora

37 - Lilly

38 - Janine

Epilogue

A READING GROUP GUIDE

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

Copyright Page

Title Page

Dedication

1 - McKenzie

2 - Aurora

3 - McKenzie

4 - Janine

5 - McKenzie

6 - Lilly

7 - McKenzie

8 - Aurora

9 - Janine

10 - McKenzie

11 - Janine

12 - Aurora

13 - Janine

14 - McKenzie

15 - Lilly

16 - McKenzie

17 - Aurora

18 - McKenzie

19 - Aurora

20 - Lilly

21 - McKenzie

22 - Janine

23 - Aurora

24 - Janine

25 - Aurora

26 - Lilly

27 - McKenzie

28 - Lilly

29 - Janine

30 - Aurora

31 - McKenzie

32 - Janine

33 - McKenzie

34 - Janine

35 - McKenzie

36 - Aurora

37 - Lilly

38 - Janine

Epilogue

A READING GROUP GUIDE

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

Copyright Page

For my sisters; you know who you are. . . .

1

McKenzie

I

don’t understand why I have to write this. Why

I

have to keep the journal. I’m the one who’s dying.

don’t understand why I have to write this. Why

I

have to keep the journal. I’m the one who’s dying.

We always keep a journal of our annual stay in Albany Beach. But I hate writing it all down as much as Aurora, Lilly, and Janine hate it. And I’m the one who’s bald and spends a good deal of my time in the bathroom puking or wishing I could puke. I would think my friends, my

dearest

friends, my closer-than-sisters, could cut me a break.

dearest

friends, my closer-than-sisters, could cut me a break.

They won’t.

According to Aurora, the unsanctioned leader of the gang, I should keep the journal precisely because I

am

dying. If my doctors’ predictions are accurate, I won’t be around next July to write the damned thing. Aurora thinks I should take my turn while the option’s still available.

am

dying. If my doctors’ predictions are accurate, I won’t be around next July to write the damned thing. Aurora thinks I should take my turn while the option’s still available.

I don’t understand why Aurora’s vote always seems to count more than mine, Janine’s, or Lilly’s. Actually I do. We all do. It’s always been that way. At least since August 17, 1986.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

I need to start at the beginning. But not the very beginning. I don’t have that much time.

Literally.

So I’ll start at the beginning of this chapter in our lives. I’ll start with my arrival at the beach house.

Literally.

So I’ll start at the beginning of this chapter in our lives. I’ll start with my arrival at the beach house.

I arrived at the beach house, for what is to be my last summer, a day earlier than the others. I planned it this way. I wanted to settle in. I wanted to get a good night’s sleep and be rested when

the girls

arrive tomorrow. (I don’t know why we still, at forty-two years old, call ourselves

girls

. We just do.) The two-hour trip from my house in northern Delaware to the beach has exhausted me. I don’t want to be exhausted when they arrive.

the girls

arrive tomorrow. (I don’t know why we still, at forty-two years old, call ourselves

girls

. We just do.) The two-hour trip from my house in northern Delaware to the beach has exhausted me. I don’t want to be exhausted when they arrive.

I also wanted to get here first so I could open up the house. This is a gift to Janine, Lilly, and Aurora. We all hate closing the house up at the end of our summer stay, but we hate opening it up more. Those first few hours always take us back too close to that August night. Each time we arrive, the ghosts have to be resurrected, then folded out of sight with the sheets and tablecloths we use to protect the furniture. The nightmare that was that night has to be swept away with the spiderwebs and mouse droppings.

No one comes to the house but us. Ever. Janine’s mom wanted to have it bulldozed. Or sold; it’s probably worth a lot of money. Two or three million, because it’s oceanfront. But she respected her daughter’s wishes and deeded it to Janine instead.

As I got out of my Honda, I looked up at the two-story Cape Cod built on pilings. I’d parked in the back; the front of the house faces the ocean. The cedar shingles have weathered to a lovely gray, but the white trim is flaking and needs painting. I grabbed a duffel bag off the backseat and leaned against the car to catch my breath. I breathed deeply, and the salty breeze stung my nostrils and revived me. Most of the windows of the house were covered with curtains or blinds, but two on the second floor weren’t.

I felt as if the house were watching me.

I took another deep breath, heaved my bag onto my shoulder, and crossed the short distance to the staircase that led up to the back deck and the back door. Beneath the house, there was a clutter of things: old rope, a bicycle leaning against the outside shower, a stack of bushel baskets from previous years’ crab feasts. I dropped my bag on the bottom step and looked for the key in a pile of empty flowerpots under the staircase. I have no idea why the flowerpots are there. No one ever stays long enough to plant flowers. Not since 1986. Could they really have been there that long?

I found the key in a Ziploc bag inside a terra-cotta flowerpot. It was on a Dolle’s keychain. Dolle’s is an icon on the Rehoboth Beach boardwalk. Saltwater taffy is their specialty, although they make caramel popcorn and other beachy treats. Janine and I both worked there when we were in high school and college.

Fingering the key, I went up the steps, half carrying, half dragging my bag. It didn’t seem this heavy when I put it in the car.

The beach cottage was built, circa 1935, on pilings that had saved it from more than one hurricane and nor’easter. Janine grew up in this house; lived here until she was fourteen. Her maternal great-grandparents had built it.

It seemed like a long way up the steps, and I was out of breath by the time I reached the top. A lousy dozen steps. I panted, trying desperately to fill my lungs with oxygen, knowing my lungs wouldn’t cooperate. I had portable oxygen in the car. “Just in case,” said my oncologist. “Just in case,” said my mother. I was afraid I was going to need it.

Technically, I have thyroid cancer, but those Machiavellian cancer cells had traveled down into my lungs. I was breathing at about forty-one percent capacity right now. It beat not breathing at all. At night, I used nebulizer treatments, which relaxed the muscles around my airways and made it easier to breathe. I’ve been putting off the supplemental oxygen albatross as long as I can, knowing my reliance on it was inevitable.

Leaning on the rail, I took long, slow, deep breaths. Shallow breathing didn’t work; it used only the top half of the lungs. Slowly, I walked across the deck to the back door. A foot seemed like a mile. The door, an oasis. I opened the screen door and slipped the key into the doorknob. Then I hesitated.

Did I really want to do this? Did I really need to scrape the scabs off these wounds

yet again?

yet again?

It wasn’t too late to cancel. I could play the Cancer Card and go home to my cozy little college town of Newark, Delaware. I could call my twin daughters, play the Cancer Card

again,

and insist they stay with me for the summer instead of their father. I could do that. I’m dying. I’d learned since my diagnosis that I could pretty much do and say anything I wanted and people would put up with it. But I couldn’t do this to my friends or my daughters because . . . because they have to go on living when I’m gone.

again,

and insist they stay with me for the summer instead of their father. I could do that. I’m dying. I’d learned since my diagnosis that I could pretty much do and say anything I wanted and people would put up with it. But I couldn’t do this to my friends or my daughters because . . . because they have to go on living when I’m gone.

Jared and I have the typical custody arrangement; our seventeen-year-olds live with me during the school year. They see their dad every other weekend, a few weeknights a month, and he gets them for most of the summer. He lives in Rehoboth Beach, within biking distance of the boardwalk. I think that when we divorced four years ago, he realized that living in a cool place might make the difference between seeing his girls once they got older and not seeing them at all. He wasn’t smart about a lot of things that year (like cheating on me with the cashier from Home Depot), but I give him credit—he thought through his move to the beach before he made it. He used to do construction in Wilmington. Now he has his own company in Rehoboth Beach. He’s doing well, well enough to pay hefty child support for our girls and keep his new wife and baby comfortable. The baby’s name is Peaches. Honest to God. It’s on the birth certificate. Who names a baby

Peaches?

Peaches?

I’m digressing again. I’d like to say it was the drugs I’m taking that make my thoughts wander, but that would be a lie. Ask my staff at the University of Delaware, where I used to be the head librarian. (Theoretically, I’m on

hiatus

. That’s what employers say when they let you go home to die.) I was like this before I had an entire pillbox of medicine to take every day.

hiatus

. That’s what employers say when they let you go home to die.) I was like this before I had an entire pillbox of medicine to take every day.

I turned the key and pushed the door open. I was assaulted by stale air and crushing memories. I picked up my bag and stepped into the laundry room that would soon be a catchall for stinky running shoes, wet bathing suits,

and

dirty clothes. It was late in the day, and the yellowing curtains over the window made the room dim.

and

dirty clothes. It was late in the day, and the yellowing curtains over the window made the room dim.

Panic fluttered in my chest. I steadied myself against the washing machine. I felt a little dizzy. Weak-kneed. I wanted to blame that on the cancer, too. Couldn’t. Every summer I felt this way the first time I stepped into this house.

I closed my eyes.

Every year, I wanted to slough off this feeling as quickly as possible, but not today. Today, I stood there and took in the whole experience: the flutter of my pulse, the faint nausea, the clammy palms. Because, feeling pain . . . feeling fear, I’d learned, meant I was still alive.

I’ll never do this again, I thought.

I’ll never walk into this house for the first time. I’ll never feel the way I’m feeling at this instant.

I’ll never walk into this house for the first time. I’ll never feel the way I’m feeling at this instant.

It passed. Quicker than you’d think it would. Another thing I’ve learned over the last year is how adaptable human beings are. What seems unimaginable quickly becomes perfectly acceptable. The first time I said, “I’m dying,” I could barely manage the words; now, I say it like I’m telling the time.

I exhaled slowly. I inhaled.

Again.

I opened my eyes. I grabbed my bag, walked through the kitchen into the big living room (that also served as the dining room), and dropped it near the staircase. It was hot in the house. Did I turn on the air or try the windows first?

I went to the floor-to-ceiling windows that ran along the front of the house, and I pushed back the long, white tulle curtains. I unlocked and slid open the windows and let the cool breeze from the ocean fill the stifling room. The late afternoon sun cast shadows on the front deck. I gazed out over the dunes, speckled with dry sea grass, intersected by a zigzagging sand fence. The ocean rippled. Pulsed. I heard the waves hit the shore. I felt them. I closed my eyes, and I really

felt

them.

felt

them.

This moment passed, too. I didn’t feel the waves anymore. I just felt silly standing there with my eyes shut.

I reached for the nearest dustcover, a pink, flowered sheet. I gave it a yank and uncovered a rocking chair. I moved from piece of furniture to piece of furniture. The living room, like the rest of the cottage, was decorated in shabby chic. It had been a group effort. I bought the white end tables and coffee table at a yard sale years ago. Janine contributed the two matching Ikea couches, covered in unbleached canvas. An ex-girlfriend had bought them. Janine didn’t want them at her place, but she wouldn’t just donate them to the Salvation Army, either. They were practically new.

I pulled a blue sheet off a faded, flowered recliner. I have no idea where it came from, but it has been here for years. I tossed the sheet in the growing pile on the floor and seriously considered sitting down in the chair. It looked so comfy, so inviting. But if I sat, I was afraid I wouldn’t get up again today. Usually my energy petered out by three. It was four thirty, and I was still feeling pretty . . . okay.

I went to the fireplace and opened the flue, afraid if I didn’t do it now, no one else would think of it and the house would fill up with smoke when we lit a fire some night. It had happened the previous year. Maybe the year before that, too. The hinges screeched, the flue opened, and I rubbed my sooty hand on my jeans.

Lined up across the mantel, at nose height, were framed photographs of us. The Fantastic Four. There was one of us in the seventh grade. Career Day. My mom took it. I reached for the five-by-seven photograph in a WE WERE FRIENDS frame.

Lilly was wearing a white lab coat and the school nurse’s stethoscope. She couldn’t get into medical school; she became an optometrist. Janine was dressed like a cowgirl, but she was wearing a shiny sheriff’s badge; now she wore a police badge. I studied myself in the photo: dark red hair pulled into a loose ponytail. Not unattractive looking, just . . . awkward.

I miss my hair. I resent my hair loss. It’s petty, I know, considering the fact that I’m about to lose my life, but I miss it anyway, and still spent too much time obsessing over it.

In the photo, I was wearing some sort of Lois Lane getup and holding a pen and a pad of paper. I had wanted to be a novelist back then, but I hadn’t known how to portray that. My mom had made me a newspaper reporter instead. At the time, I remember thinking it was a dumb idea but had gone with it for lack of a better one at seven a.m. the morning of Career Day.

Aurora, with her blond hair, was at the very edge of the frame, wearing her school uniform, a French beret, and sporting a tiny black mustache she’d drawn above her upper lip with eyeliner. She’d wanted to be an artist. Her dream had come true. Aurora always got what she wanted.

I rubbed the dust off the top of the frame with my finger and put it back on the mantel. There was more dust. There were more pictures, pictures taken after August 1986. After Buddy died. After Janine cut her hair. After Lilly lost her mom. After I became the ordinary person I never wanted to be. But I didn’t linger there any longer. We’d be here a month; there would be plenty of time to dust and reminisce.

I grabbed my duffel bag to take it into the front bedroom. We’d already agreed, in e-mails going back and forth, that I’d sleep here. Janine’s parents’ bedroom. It looked nothing like it did when

he

slept here, but it still creeped me out. I would rather have slept upstairs in the little room Lilly and I had always shared. But the girls were right; that made no sense. Stairs and cancerous lungs—oil and water. I left my bag on the floor, just inside the doorway. I went back into the living room and stared up the staircase. I didn’t know why, but I wanted to go up. Now? Later?

he

slept here, but it still creeped me out. I would rather have slept upstairs in the little room Lilly and I had always shared. But the girls were right; that made no sense. Stairs and cancerous lungs—oil and water. I left my bag on the floor, just inside the doorway. I went back into the living room and stared up the staircase. I didn’t know why, but I wanted to go up. Now? Later?

Now.

I took two more deep breaths and slowly attacked the stairs, one step at a time. I longed for the days when I could run up these stairs. Hell, two summers ago I’d chased Lilly up, then back down, when she stole my cell phone and was reading sexts from my then-boyfriend aloud to the others. The relationship hadn’t lasted. In retrospect, I realized I hadn’t liked him as much as I had liked the

idea

of him. It was a big deal when he broke up with me. Not such a big deal now.

idea

of him. It was a big deal when he broke up with me. Not such a big deal now.

My chest was tight. I had to pause. I felt as if I was physically breathing, but there wasn’t enough oxygen getting to my cells.

Was this what it would feel like to suffocate?

That was what everyone with tumors in their lungs feared. Suffocating. It’s the way it happens—lung cancer death—though no one wants to come out and say it. That’s the kind of information you find on the trusty Internet.

Was this what it would feel like to suffocate?

That was what everyone with tumors in their lungs feared. Suffocating. It’s the way it happens—lung cancer death—though no one wants to come out and say it. That’s the kind of information you find on the trusty Internet.

Other books

Deliberate Display - five erotic voyeur and exhibitionist stories by Felthouse, Lucy, Marsden, Sommer, McKeown, John, Yong, Marlene, Thornton, Abigail

Mostly Sunny with a Chance of Storms by Marion Roberts

Forsaken by Leanna Ellis

Bring Me the Horizon by Jennifer Bray-Weber

The Ballad of Gregoire Darcy by Marsha Altman

Meaner Things by David Anderson

Rise of the Lost Prince by London Saint James

Evergreen Falls by Kimberley Freeman

Shattered: The Iron Druid Chronicles, Book Seven by Kevin Hearne

Love & Loss by C. J. Fallowfield