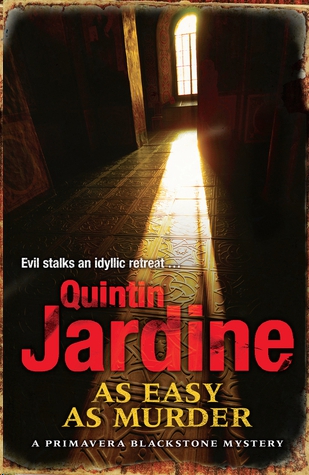

As Easy as Murder

Authors: Quintin Jardine

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #World Literature, #Mystery; Thriller & Suspense, #Mystery, #Women Sleuths, #Crime Fiction, #Private Investigators, #Scotland

QUINTIN JARDINE

Copyright © 2012 Portador Ltd

The right of Quintin Jardine to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published as an Ebook by Headline Publishing Group in 2012

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Cataloguing in Publication Data is available from the British Library<

eISBN: 978 0 7553 5385 9

HEADLINE PUBLISHING GROUP

An Hachette UK Company

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

‘A triumph. I am first in the queue for the next one’

Scotland on Sunday

‘Perfect plotting and convincing characterisation . . . Jardine manages to combine the picturesque with the thrilling and the dream-like with the coldly rational’

The Times

‘Engrossing, believable characters . . . captures Edinburgh beautifully . . . It all adds up to a very good read’

Edinburgh Evening News

‘[Quintin Jardine] sells more crime fiction in Scotland than John Grisham and people queue around the block to buy his latest book’

The Australian

‘Remarkably assured . . . a tour de force’

New York Times

‘There is a whole world here, the tense narratives all come to the boil at the same time in a spectacular climax’

Shots

magazine

‘A complex story combined with robust characterisation; a murder/mystery novel of our time that will keep you hooked to the very last page’

The Scots Magazine

This is for the lovely Frida Teixidor and her lovely daughter.

S

he’s a truly sad person, she who can harden her heart against the joyous sound of children at play!

. . . but sometimes the incessant squeal of a swarm of the little buggers would grate on the nerves of the Blessed Virgin herself. Was there never a time, maybe from the years 3, to 6 or 7

AD

, when she didn’t turn on Him and yell, ‘For Christ’s sake, Jesus! Would you allow me five minutes of peace and quiet? Is that too much to ask?’

In Plaça Major, the centrepiece of the village of St Martí d’Empuriès, the enchanted Catalan village that I, Primavera Blackstone, Phillips as was, and my son Tom, have called our home for the last five years or so, the fourth Arrels del Vi . . . the proper name of the annual wine fair . . . was in the fullest swing. Since it moved a couple of those years ago from its original, smaller site, it’s become a magnet for family groups. Now Mum and Dad can bring the nippers along while they wander among the stalls and sample the best that Emporda can offer, knowing that they have room to play in front of the church, and my house, which is bang next door.

At any other time, I’d have been amused, probably even charmed, but that was not the best day of my life. I’d arrived home with Tom from a clothes-shopping trip to Girona . . . for him, he’s ten and seemed to have been taking a growth hormone (now there’s an ironic analogy) behind my back; I’m not short, yet he’s up to my shoulder already, and solidly built with it . . . to find that when we’d been out the post person had called, on her wee yellow scooter. I knew this because Ben Simmers, who created and runs the fair, had spotted a letter sticking out of the top of my mail box, and had rescued it, and three others, before anyone else could. Two of those others were bills. The third was a letter acknowledging my resignation from a part-time job I’d held for a couple of years. I’d been a sort of . . . how best to describe myself? . . . honorary consul, with a remit to promote Scottish interests and business on behalf of the Edinburgh government.

The role had involved lots of travel around Catalunya and beyond, throughout the rest of Spain. I’d enjoyed it for a while, but it had only been possible because I’d been able to employ a young woman called Catriona O’Riordan to look after the house, Tom, and Charlie, our amiable idiot Labrador retriever, during my weekly absences. When I was there she took it upon herself to run all three of us, and I was fine with that. Catriona was great;

irreplaceable, as it turned out. When family circumstances forced her to go back to Britain, I’d looked apathetically for a successor, but none of the CVs that I was sent appealed to me, and so I decided, after not too much internal debate, that since being a full-time mum is what I’m best at, that’s what I should go back to doing.

The job had been useful at the beginning, though. Not because we needed the money . . . we don’t, and we never will . . . but because it took me out of myself, and out of St Martí at a time when, without it, I’d probably have spent too much of my time sitting around brooding.

About what? Not what, whom: a man, of course, the only one who’s ever come close to making me go all domestic, other than Tom’s dad . . . although here I need to volunteer that my brief attempt at a conventional lifestyle with Oz Blackstone ended in disaster so acrimonious that our son was three and a half years old before his father even knew of his existence.

God, I can’t even tell this tale without getting myself sidetracked, all screwed up with angst and regret over my years with that guy. When they were over, irrevocably, as death tends to be, and I was able to consider them, and him, from a distance, I did some internet research that led me to a pretty unshakeable conclusion. When I looked at fifteen behavioural traits indicative of anti-social personality disorder, I found that my former husband ticked fourteen of those boxes. The experts say that particular condition is something you’re born with, but none of them ever knew my ex. The Oz Blackstone that I met was lovely, open, honest and brave, just as his son is growing up to be.

But things happened, and they transformed him.

I had a rival for his affections. She won out for a while, but then she was killed, murdered, and that, I am certain, triggered a change in him, and turned him into what he became, a classic sociopath.

And yet, I loved that Oz too. Having admitted that, I made myself go deeper and looked at myself in the same context, to be faced with another truth. There was a period in my life when, in my relationship with him if nowhere else, I was pretty similar myself.

But it’s over, Primavera, it’s over, he’s dead. Forget the bad that he was, and concentrate on the good that he’s left behind him in our son.

Fine, with an effort of will, I do that and I come to the man who’s come closest to filling what others . . . but not I, never I . . . see as a gap in my life. There was a time two years ago, a brief moment when I thought that all things might have been possible. If Gerard Hernanz had asked me to, I might even have left St Martí for him. It would have been difficult for me to walk away from paradise, but I believe I’d have given it a try. So would Tom, I’m sure, because he liked the man too. He didn’t worship him in the way that he keeps his father’s memory alive in his heart, but if I’d put it to him he’d have followed my lead with only a little regret.

However, it didn’t come to that. Once again, unforeseeable events got in the way. Gerard lost someone very close to him, and he felt that he needed to go away to consider his future at length, to discover whether he was able to turn his back completely on a

previous relationship, one that had been his career also: his priesthood within the Roman Catholic Church.

The fourth item in my Saturday post was his decision. I won’t burden you with the text of his letter . . . I couldn’t anyway, even if I had a mind to, for it went through the shredder that same evening . . . but what he told me was that while he wasn’t returning to his ministry, he wasn’t returning to me either. He’d spent two years teaching in a monastic school in Ireland. There, he said, he’d found the sort of peace that had eluded him all of his life. He had thought about coming back to St Martí, to build a life with Tom and me, but he had realised that it would involve challenges that might be beyond him and he was concerned about the damage that failure would do to all of us, and most of all to Tom, whose interests he placed above our own. And so, with the blessing of his abbot, he had decided to commit his life to his cloistered pupils.

It was after my second reading of his epistle that the noise below my balcony began to grate on me. I could do nothing about it, so I took the letter off to my bedroom, which has a secluded terrace overlooking the sea, and went through it another couple of times, looking for any sign that he might really be expecting me to respond, to fight my corner against the bloody Benedictines, to write back to him protesting, ‘Bollocks to that, get yourself back here.’

But there was none, I concluded. What he was telling me was unequivocal, with no sign at all of an uncertain man waiting to be persuaded. The more I studied what he was saying, the more my respect for him wore away. The way that I saw it, he was using my

ten-year-old son as cover for the blatant lack of guts he was displaying, either in not taking a chance on life, or in not telling me he didn’t really fancy me. He’d come to know Tom well, and he must have appreciated that the real boy was a lot tougher than the one he was describing. Tom seemed to have dealt with his father’s early death and built on his spirit; in truth there had been moments when his strength had reinvigorated me. If we’d tried, and it didn’t work out between Gerard and me, the same thing would happen, I was sure. He’d give me a hug and we’d move on.

But what about me? What did I really want? Two years before, Gerard had asked me to give him space, and I’d done that. Eh? Pardon? Me? I frowned at the page, and asked myself a straight question, for the first time. Wouldn’t the real Primavera, if she’d wanted him badly enough, have gone to Ireland a long time before and laid it on the line for him? ‘Dinner’s in the oven, sunshine. Get your ass back home!’

Of course she would. So why hadn’t she? For make no mistake, that woman still exists.

I didn’t have to dig far for the answer to that. The bald truth was that even if Gerard Hernanz had never gone, if instead he’d stayed put in St Martí two years before, and I’d taken him into my home and into my bed, he’d always have been second best.

Inside, the real Primavera would still have dreamed that the dead might arise and walk once more, as she’d done herself in a manner of speaking, after a spell of hiding in mistaken fear.

Inside, she still does.

‘Are you all right, Mum?’

‘Because you promised you’d come out to the wine fair with me, remember. I sniff, you taste, that was the deal. You never forget a promise, so something must have upset you.’

He’s not a boy you can fob off. ‘I’ve had a letter,’ I told him. ‘From Ireland. From Gerard.’

‘And he’s not coming back.’ There was no question mark left hanging in the air.

‘No, he’s not. I’m sorry, Tom.’

He shrugged his shoulders, in a Scottish way rather than his usual Catalan. (Linguistic shrugging is complex; it has to be seen to be understood.) ‘I’m not,’ he declared, firmly; then he paused. ‘Well, I’m sorry for you, Mum, if that’s what you wanted. But not for myself. I don’t need . . .’

His years and his vocabulary weren’t yet at the point where he was able to articulate the concept that while he might have liked Gerard as a man, he had no room for him in his life as an added authority figure, but that’s what he meant.

The letter hadn’t brought the merest hint of mistiness to my eyes, but that did. Before he saw it and misunderstood, I jumped to my feet, beaming. ‘And neither do I,’ I declared. I slung an arm round his shoulders, something that I’m able to do these days without bending at all. ‘Come on, kid. Time for you to do some serious sniffing.’