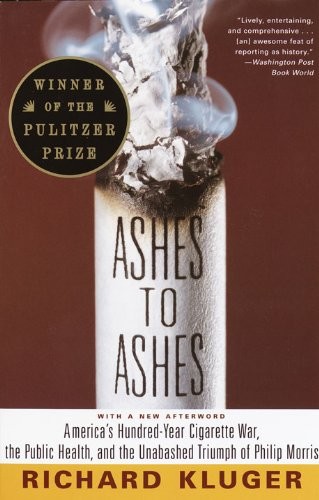

Ashes to Ashes

Authors: Richard Kluger

Acclaim for

Richard Kluger’s

ASHES TO ASHES

“Unwinds almost like a Greek tragedy. … The definitive—and very fair—history of the most controversial industry of our time.”

—

Business Week

“Rich in detail … an intricately layered, comprehensive narrative.”

—

Los Angeles Times Book Review

“[An] excellent history.”

—

The New Yorker

“Magisterial … full of fascinating digressions.”

—

The New Republic

“Ashes to Ashes

will stand as the authoritative source on how we wound up in a disastrous dilemma.”

—

Wall Street Journal

“Epic history … elegantly written … it will probably be the definitive volume on the subject of cigarettes in the 20th century.”

—

Time

“An excellent work … . Well-balanced and thought-provoking.”

—

New England Journal of Medicine

“Has more intrigue, is more frightening, and is more powerful than John Grisham’s new thriller.”

—

USA Today

“Will no doubt serve as the standard history of the tobacco industry for many years to come … . A sweeping narrative full of outsized personalities and sudden twists of fortune.”

—

The New York Review of Books

ALSO BY RICHARD KLUGER

History

SIMPLE JUSTICE:

A HISTORY OF BROWN V. BOARD OF EDUCATION AND

BLACK AMERICA’S STRUGGLE FOR EQUALITY

THE PAPER: THE LIFE AND DEATH

OF THE NEW YORK HERALD TRIBUNE

Novels

WHEN THE BOUGH BREAKS

NATIONAL ANTHEM

MEMBERS OF THE TRIBE

STAR WITNESS

UN-AMERICAN ACTIVITIES

THE SHERIFF OF NOTTINGHAM

Novels with Phyllis Kluger

GOOD GOODS

ROYAL POINCIANA

Richard Kluger

ASHES TO ASHES

Richard Kluger, a Princeton graduate, worked as a journalist with

The Wall Street Journal, New York Post

, and the

New York Herald Tribune

, on which he was the last literary editor, before entering book publishing. After serving as executive editor at Simon and Schuster and editor in chief at Atheneum, he turned to writing fiction and social history. He is the author of six novels (and two others with his wife, Phyllis), two National Book Award finalists—

Simple Justice

and

The Paper

(a history of the Herald Tribune)—and a Pulitzer Prize-winning history of the American cigarette business,

Ashes to Ashes

. He and his wife now live in Berkeley, California.

With love for Phyllis, my life’s companion,

who is all too familiar with the subject

Tobacco, I do assert … is the most soothing, sovereign and precious weed that ever our dear old mother Earth tendered to the use of man! Let him who would contradict that most mild, but sincere and enthusiastic assertion, look to his undertaker …

.

BEN JONSON

For thy sake, Tobacco, I

would do anything but die

.

CHARLES LAMB

Smoke, smoke, smoke that cigarette

.

Puff, puff, puff and if you smoke yourself to death

,

Tell Saint Peter at the Golden Gate

That you hate to make him wait

But you’ve got to have another cigarette

.

“SMOKE! SMOKE! SMOKE!”

1947

SONG BY MERLE TRAVIS AND

TEX WILLIAMS

Contents

2

The Earth with a Fence Around It

3

It Takes the Hair Right Off Your Bean

5

“Shall We Just Have a Cigarette on It?”

6

The Filter Tip and Other Placebos

7

The Anguish of the Russian Count

13

Breeding a One-Fanged Rattler

15

The Calling of Philip Morris

16

Of Dragonslayers and Pond Scum

17

Chow Lines

Afterword to the Vintage Edition

A Note on Sources and Acknowledgments

Foreword:

A Quick Drag

A

s

THE

twentieth century wanes, we may marvel justifiably at the triumphs of the human intellect in the course of this span over the visitations of nature at its unkindest. We have largely overcome the savaging effects of infection and contagion, of extreme climates and turbulent weather, of famine and peril from other species. We have attacked the vastness of our planet’s distances, even the force of gravity itself, while unlocking the earth’s elemental secrets. We have generated creature comforts and pleasures on a scale undreamed of by our forebears and doubled our expected life span.

Yet, as if to reassure the overseers of the universe that we have not attained godlike status but remain in essence creatures of folly and victims of our darker natures, we have also ingeniously crafted fresh forms of misery and death-dealing. We have generated vile effluents with our life-enhancing technology, fouling soil, waters, and skies in ways only beginning to be understood. We have fashioned doomsday weaponry. We have promoted mindless tribal hatreds into genocide and rationalized it in the name of profane statecraft. And worst of all, if we are to credit the number of fatalities as calculated by public-health authorities, twentieth-century man has embraced the cigarette and paid dearly for it.

The stated toll is horrific. Americans are said to die prematurely from diseases caused or gravely compounded by smoking at the rate of nearly half a million a year; a multiple of that figure is put forward as the world toll, approaching several million. The number claimed has risen appallingly as the century has lengthened, population and wealth have grown, and social customs have turned more permissive. No one can make more than an informed guess

at the total loss of life, but those decrying it most urgently assert that the mortality figure from smoking for the century as a whole rivals the multimillions who have fallen in all its wars.

Yet there has been little outrage at the appalling statistics—only a dirgelike, loosely orchestrated, and inconstant chorus of protest over the continuing practice of the custom and, increasingly of late, restrictions on where it may be undertaken. At mid-century, nearly half the adult American population smoked; near the end of the century, despite massive indictment of the habit by medical science, more than a quarter of all Americans over eighteen continues to smoke—nearly 50 million people. And while overall consumption has declined somewhat, those who cling to the custom smoke more heavily than ever: an estimated twenty-seven cigarettes a day on average. Meanwhile, in Asia, Africa, and Eastern Europe, tobacco is a growth industry. There the cigarette is widely regarded as a sign of modernity, an emblem of advancement, fashion, savoir-faire, and adventure as projected in images beamed and plastered everywhere by its makers. And, in a case of supreme irony, not to say perversity, the more evidence accumulated by science on the ravaging effects of tobacco, the more lucrative the business has become and the wider the margin of profit.

Why should this be? Did mankind simply become putty in the hands of the master manipulators who ran the cigarette business? Were we so charmed by the iconography with which these marketing Svengalis enriched our popular culture—a fantasyland populated by heroically taciturn cowboys, sportive camels, and an array of young lovers, auto racers, and assorted bons vivants all vibrantly “alive with pleasure”—that we exonerated them from all charges of capital crimes?

Or have we been convinced by these merchants’ unyielding insistence that peddling poison in the form of tobacco is no vice if (a) it is freely picked by its users and (b) its dangers have not yet been conclusively, to the last logarithm of human intellect, proven? Or perhaps our complicity in this man-made plague stems from our very familiarity with the subject; the product has become so ubiquitous and the case against it so clear that we are plain bored by the whole matter. Or perhaps it is the circumstances of death from smoking. The toll is slowly exacted, in the form of seven or eight years of lost life to the average smoker, who, like the rest of us, succumbs mostly to the degenerative diseases of old age: cancer, failing hearts, blocked arteries, dysfunctional lungs. Death from such causes comes singly, and usually at hospitals, not in spectacular conflagrations or crashes obliterating hundreds at a time and capturing the world’s attention and sympathy. The smoker’s death is banal, private, noticed only by family and friends, and, in the final analysis, self-inflicted.

Doubtless there is an element of plausibility in each of these explanations,

but the persistent sway of the cigarette may be equally understood by dwelling not on the consequences of the habit, as its detractors naturally do, and why these people

ought

to have curtailed it, but on the reason for the phenomenon in the first place. Simply put, hundreds of millions worldwide have found smoking useful to them in myriad ways, subconscious or otherwise.

The proverbial visitor from a distant planet would likely find no earthling custom more pointless or puzzling than the swallowing of tobacco smoke followed by its billowy emission and accompanying odor. Told that the act neither warms nor cleanses the human interior, that it neither repels enemies nor attracts lovers, our off-planet visitor would be still more baffled. The utility of the exercise, he/she/it would be informed, is traceable to the changing pace, scale, and nature of daily living in this century. Our lives used to be simpler and shorter, given over largely to the struggle for survival. But the technological marvels of our age have provoked attendant stresses from congested living and our often grating interdependence; from the irksome nature of our duties and lack of time to accomplish them; from a welter of conflicting values and emotions born of unattainable expectations and unmanageable frustrations; and from the often careening velocity of life. Many of us have lacked the inner resources to get through the battle and gain a little repose without help wherever and however we could find it, and no device, product, or pastime has been more readily seized upon for this purpose than the cigarette. It has been the preferred and infamous pacifier of the twentieth century, even as—or if—it has been our worst killer. Its users have found it their all-purpose psychological crutch, their universal coping device, and the truest, cheapest, most accessible opiate of the masses.

Let us consider, then, this protean usefulness of the cigarette, which, practically speaking,

is

the tobacco business in the United States, accounting for some 95 percent of the industry’s revenues. The unique value of the cigarette to its users has resided in its perceived dual (and contradictory) role as both stimulant and sedative. Clinically, smoking has been found to speed up a number of bodily functions, most notably the flow of adrenaline, with its quickening effect on the beat of the heart, but the smoker when questioned will most often characterize the cigarette as a relaxant. This seeming paradox is the essence of the product’s appeal, for in fact, the smoker uses it to meet both needs.

The smoker smokes when feeling up or in the dumps, when too harassed and overburdened or too unchallenged and idle, when threatened by the crowd at a party or when lonely in a strange place. A smoke is a reward for a job well done or consolation for a job botched. It can fuel the smoker for the intensity of life’s daily confrontations yet seem to insulate him from the consuming effects of any given encounter. It defines and punctuates the periods of the smoker’s day, and nothing helps as much in dealing on the telephone with

trying people or unpleasant matters. The cigarette, in short, has been the peerless regulator of its user’s moods, the merciful stabilizing force against the human tendency to overrespond to the infinite stimuli that inescapably impinge upon us.