Asking For Trouble

Asking For Trouble

Ann Granger

Copyright © 1997 Ann Granger

The right of Ann Granger to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published as an Ebook by Headline Publishing Group in 2013

Apart from any use permitted under UK copyright law, this publication may only be reproduced, stored, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, with prior permission in writing of the publishers or, in the case of reprographic production, in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency.

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Cataloguing in Publication Data is available from the British Library

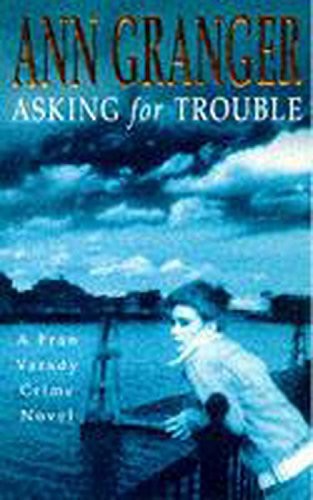

Cover photograph by Mike Trevillion

eISBN 978 0 7553 7723 7

HEADLINE PUBLISHING GROUP

An Hachette UK Company

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

Table of Contents

Ann Granger has lived in cities all over the world, since for many years she worked for the Foreign Office and received postings to British embassies as far apart as Munich and Lusaka. She is married, with two sons, and she and her husband, who also worked for the Foreign Office, are now permanently based in Oxfordshire.

Praise for Ann Granger’s crime novels:

‘A host of entertaining and lifelike characters. And there is a satisfying and entertaining twist on the last page’

Mystery People

‘Characterisation, as ever with Granger, is sharp and astringent’

The Times

‘The plot is neat and ingenious, the characters rounded and touchingly credible, and the writing of this darkly humorous but humane and generous novel fluent, supple and a pleasure to read’

Ham and High

‘The reader can expect a treat. Lively, different and fun’

Yorkshire Post

‘Ann Granger’s skill with character together with her sprightly writing make the most of the story. . .she is on to another winner’

Birmingham Post

By Ann Granger and available from Headline

Fran Varady crime novels

Asking For Trouble

Keeping Bad Company

Running Scared

Risking It All

Watching Out

Mixing With Murder

Rattling The Bones

Inspector Ben Ross crime novels

A Rare Interest In Corpses

A Mortal Curiosity

A Better Quality Of Murder

A Particular Eye For Villainy

The Testimony Of The Hanged Man

Campbell and Carter crime novels

Mud, Muck And Dead Things

Rack, Ruin And Murder

Bricks And Mortality

Mitchell and Markby crime novels

Say It With Poison

A Season For Murder

Cold In The Earth

Murder Among Us

Where Old Bones Lie

A Fine Place For Death

Flowers For His Funeral

Candle For A Corpse

A Touch Of Mortality

A Word After Dying

Call The Dead Again

Beneath These Stones

Shades Of Murder

A Restless Evil

That Way Murder Lies

Fran Varady is insolvent, unemployed and, though for the moment she’s got the leaky roof of the squat she shares in Jubilee Street over her head, thanks to the council eviction department she’ll very soon be homeless. Her dreams of becoming an actress, nurtured when her father and grandmother were still alive, seem a long way off. But the quietly resolute Fran is a survivor. Which her former housemate, Terry, found hanging from the ceiling rose of her room, clearly is not.

Terry, secretive and selfish, was far from popular with the rest of the household, but her death shakes the Jubilee Street Creative Artists’ Commune, as the squat residents half jokingly call themselves. And, the more Fran discovers about the death of the young woman whose life briefly intersected with her own, the more she begins to see it was not all it first seemed.

The man from the council housing department came on Monday morning. He served us with summonses, one each.

‘According to our procedure!’ he informed us in a voice pitched nervously high. He wasn’t very old, curly-haired, his round cherubic face doing its best to express authority but losing out to an expression of incipient panic.

I can’t believe he was seriously scared of us. Granted we outnumbered him but we weren’t strangers. He, and various of his colleagues, had been before. In the past we’d locked them out, so that they had to shout up at the windows to communicate with us. But that day we’d let him in. It was decision day. We knew it and he knew that we did. There was no longer any point in those spirited exchanges hurled between pavement and windowsill. It was a curiously muted ending to a long-running dispute.

All the same he watched us anxiously, just in case we tore up the individual summonses in a last protest. Squib took his from its envelope and turned it over as if he expected to see something written on the back. Terry pushed hers into the pocket of her knitted coat. Nev looked for a moment as if he were going to refuse to accept his, but took it eventually. I took mine and said, ‘Thanks for nothing!’

The official cleared his throat. ‘I shall be attending the court tomorrow, together with the council’s solicitor, to apply for an order for immediate possession. We anticipate it will be granted. We’re prepared to give you until Friday to enable you to find alternative accommodation. But the matter is now in the hands of the court and its bailiffs. So it’s no use arguing with me! Argue it out with the court tomorrow, if you want. But it won’t do any good.’

He was still defensive, though no one bothered to answer him. We’d always known we’d lose. Even so, the reality of knowing we were out induced a physical sickness in the stomach. I turned away and stared at the window until I could control my face.

It was one of those slate-coloured mornings, threatening to tip rain at any moment, though it would probably hold off until evening. Dense cloud cover kept the traffic fumes and other odours trapped at street-level. You could even smell the charred meat and burnt onions from the Wild West hamburger bar which was two streets away.

I hadn’t been feeling very cheerful that morning, even before our visitor came, because I’d lost my job the previous Friday. The manager had found out that my address was ‘irregular’ and that was that. Irregular meant I was currently living in a squat.

Although technically our occupation was illegal, no one had prevented us moving into an empty – and to all intents ownerless – house, and now we’d been there long enough for our presence to have acquired an air of permanency. Moreover, we had a purpose. We called ourselves the Jubilee Street Creative Artists’ Commune, though none of our work would have attracted a subsidy from the Arts Council or the National Lottery. But in between conforming to the norm or plummeting to the depths, whatever our individual destinies might be, we planned stupendous careers from the anonymity of Jubilee Street. In every way we possibly could, in fact, we deceived ourselves. Dreams beat reality any day.

By the way, I have to leave Squib out of the great careers scenario. Squib lived strictly from day to day and hadn’t formed even the ghost of a plan that anyone had ever heard of.

Nev had plans. They came in the form of a twenty-page synopsis for his novel, which was likely to rival

War and Peace

in length. Every day he tapped away relentlessly on an old W H Smith manual machine. I’ve sometimes wondered if he ever finished it.

Squib was a pavement artist. He could copy anything. Some people would say that wasn’t truly creative because it wasn’t original, but they hadn’t seen what Squib could do with a box of chalks and a few clean slabs. Old masters, which had been reduced by familiarity and brown varnish to the status of museum pieces, emerged breathing new life from Squib’s fingers. They spoke so eloquently to passers-by that several were visibly disconcerted by the vibrancy of the chalked faces at their feet. In an episode which Squib regarded as deeply embarrassing, a passing art critic became so enthusiastic that he talked of presenting Squib to the world, together – presumably – with some purpose-acquired slabs to work on. The idea of being taken up by the establishment had so terrified Squib that he’d simply melted away with his tin of chalks and taken to improving the pavements of the provinces until he thought it safe to return to London.

As for me, I still clung to my early ambition to be an actress. Life had somewhat got in the way. I’d dropped out of a college course in the Dramatic Arts. Since then, apart from some Street Theatre, the role of star of stage and screen had eluded me. I still hoped to make it some day. Short term, keeping the wolf from the door was enough to occupy me. That, and maintaining an eye on the other two.

We three had moved into the house first. Soon afterwards we’d been joined by Declan, a small wiry fellow with straggling shoulder-length hair and features like a good-natured elf. Both his arms had been heavily tattooed: a fearsome snake on one; a sacred heart on the other. He recalled having the sacred heart done, but claimed to have no recollection of the snake being tattooed. He’d woken up one morning with a monumental hangover and there it was, crawling up his arm. ‘I thought I had the DTs,’ he observed. Sometimes he’d stretch out his arm and study the snake thoughtfully. I think it worried him.

Declan had arrived as a rock musician without a group, owing to his former group’s lead guitarist having been accidentally electrocuted whilst rehearsing in a church hall.

‘The poor sod’s hair stood on end,’ Declan would relate with mournful wonder. ‘God rest his soul, it was bloody funny to see. Until we realised he was dead, you know. That sobered us up. We all stood round trying to remember how to do resuscitation while we waited for an ambulance. Though we could see he was a goner. On top of which, the amp was just about fried and we hadn’t got the dosh to buy another. Just then, would you believe it? A wee man came running in, mouthing off at us because we’d fused all the lights in the place. It pissed us off that much, him no showing any respect for the dead like it, that the drummer and I, we picked him up, kicking and yelling like a banshee, and dropped him out of the window. It wasn’t a long drop. He bounced. But we got done for assault, all the same.’

Declan played bass and a bass-player needs a group.

A little later Lucy and her two children had come along. Lucy wasn’t an artist of any sort. She’d run away from a violent husband and had been staying at a battered women’s refuge a few streets away. I’d got talking to her one day while I was serving in Patels’ corner greengrocer’s shop. She was buying carrots for the children to gnaw. Raw carrots are full of vitamin C, don’t contain the sort of acids which drill holes in tooth enamel, and are cheaper than most fruit.