Read Assassination: The Royal Family's 1000-Year Curse Online

Authors: David Maislish

Tags: #Europe, #Biography & Autobiography, #Royalty, #Great Britain, #History

Assassination: The Royal Family's 1000-Year Curse (6 page)

With regard to the ‘accident’, the facts make it almost impossible to see anything in this other than murder.

The man who shot the arrow was Sir Walter Tyrrell, Lord of Poix in Normandy. He is said to have claimed that William had been hiding behind some cover, and had stood up and shot an arrow at a passing deer, wounding it. Then another deer had run past, and Tyrrell, who was standing on the other side of the clearing, had shot at that second deer, had unfortunately missed it completely (despite his renown as an expert shot), and even more unfortunately William was still standing up and by an amazing piece of bad luck the arrow glanced off an oak tree and struck him in the heart. Regrettably, William was unaware of the danger, as at that very moment he was shielding his eyes from the sun. For a final piece of misfortune, despite being struck in the chest, William fell forward to the ground, forcing the arrow through his body, thereby ensuring his death.

One account claims that when Tyrrell was asked how he did not see the King, he replied that he had mistaken the King’s red beard for a squirrel. Whether he said this or not, the fact remains that all the excuses made to suggest that this was an accident were just too ridiculous. In all probability the King was murdered, although the story of an accident was accepted at the time. Perhaps accusing the new king of being part of a conspiracy to murder the last king would not have been a good idea.

The Rufus Stone in the New Forest

The Rufus Stone in the New ForestTyrrell later denied that it was his arrow that struck the King. That denial is not assisted by the fact that Tyrrell instantly made for the coast, where a boat was waiting to take him to Normandy. He never returned to England.

More circumstantial evidence points at Henry. Apart from Henry needing to stake his claim before Robert returned from crusade, William was refusing to allow Henry to marry Edith, the daughter of the King of Scotland and the niece of Edgar the Atheling. That was a union that would hugely increase Henry’s acceptability as king.

Murder was not a predicament in itself, but there was a pitfall; if Henry killed the King, it might endanger his chances of the succession as far as the Church was concerned. He had to get someone else to do it.

The Clares were great friends of Henry; the family was descended from Geoffrey Count of Eu, the son of Duke Richard I of Normandy. Gilbert de Clare and Roger of Clare were two of the lords at the hunt. After William’s death, when Henry rushed to Winchester, it was the Clare brothers who travelled with him. At Winchester, they were met by William Giffard, who was the Lord Chancellor and the uncle of Gilbert and Roger, and he helped them to seize the royal treasury. Then Giffard, Gilbert and Roger rode with Henry to London, where he claimed and obtained the crown.

Were they rewarded? The day after the murder, William Giffard was installed as Bishop of Winchester; Gilbert de Clare was already Earl of Hertfordshire, he would soon become Lord of Cardigan; Roger inherited his father’s Norman lands and was appointed one of Henry’s most senior military commanders; their brother Robert of Clare was appointed Steward to the King and was granted the title of Lord of Little Dunmow; another of the Clare brothers was a priest, he was given the abbacy of Ely.

But why would the Clares select Tyrrell? They had to choose someone whose presence would not be suspicious – Tyrrell (whose grandfather had fought alongside William the Conqueror at Hastings) was an unsurprising invitee to the hunt. They needed someone who was a good shot – Tyrrell was an expert marksman. They needed someone who would not be available for questioning or trial after the killing – Tyrrell lived in Normandy, and was clearly willing to leave England for good. Most of all, they needed someone who was close to the other conspirators and whom they could trust – Tyrrell was married to Alice, sister of Gilbert de Clare and Roger of Clare.

Walter Tyrrell, having returned to Normandy, brazenly selected the stag’s head for the motif on his shield. Then, funded by whatever reward he may have received for the coldblooded murder of the King, he went on crusade and died in the Holy Land.

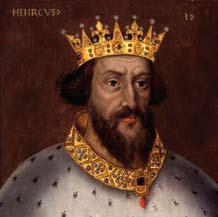

HENRY I

3 August 1100 – 1 December 1135

Henry seized the throne in 1100 on the death of his brother, William II. It was at a time when the oldest son of the Conqueror, Duke Robert, was travelling in Europe, coming home from crusade.

Having missed out again, Robert decided on invasion. He landed with his army near Portsmouth; but Henry bought him off, and Robert returned to Normandy. It was not long before the two brothers were once more at war. On the fortieth anniversary of his father’s landing in England, Henry conquered Normandy. The victory was well received by the English, and many saw it as a reversal of the humiliation of Hastings.

Despite defeat, Robert was still a threat, so Henry had him locked up, first in Devizes Castle and then in Cardiff Castle. He remained there for the rest of his life.

Henry had solidified his position by marrying Edith, daughter of the King of Scotland and niece of Edgar the Atheling. That marriage, together with the fact that Henry had been born in England, helped to establish him as an English king in the eyes of many of the Anglo-Saxons. Even better,

HENRY I and MATILDA

Agatha =========Edward Edmund of Hungary the Exile

Edgar Margaret ====== King the

Atheling Malcolm III of Scotland Christina WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR (r. 1066-87)

several children Matilda ============================ HENRY (Edith) (r. 1100-35)

Henry’s children would be the great-great-grandchildren of King Edmund Ironside. However, the marriage itself was a rather loose arrangement, as Henry is believed to have fathered more than 20 illegitimate children.

Being the youngest son, Henry had been destined to become a bishop, so he received a far better education than any of his brothers. That enabled him to introduce many judicial and financial reforms. Nevertheless, to his subjects Henry’s reputation was that of a ruthless and cruel man. The greatest illustration of his cruelty is provided by the tale of Eustace de Pacy and Ralph Harnec, two feuding nobles who had exchanged children as hostages for good behaviour. Eustace decided to continue with the feud, so he blinded Harnec’s son. Harnec complained to Henry. Having considered the matter, Henry announced that Harnec was now entitled to blind Eustace’s two daughters – this, despite the fact that those two girls were Henry’s own grandchildren, Eustace having married Henry’s illegitimate daughter, Juliane. After the two children had been blinded, the furious Juliane demanded to see her father. Henry agreed, he had no difficulty in justifying his decision, it seemed perfectly reasonable.

Juliane stormed into the hall in the Castle of Breteuil, carrying a crossbow. She lifted it, aimed at Henry and let fly; but with Juliane struggling to hold the heavy weapon steady, the arrow missed. Immediately seized and imprisoned, Juliane climbed out of a window, jumped into the moat and escaped. In later years, Juliane and Henry agreed to put it all behind them, and they were reconciled.

In 1119, Louis VI of France invaded Normandy, determined to seize it for William the son of the imprisoned Duke Robert (that son being called ‘the Clito’ – the Latin equivalent of Atheling). He met Henry at the Battle of Bremule. Victory was Henry’s; but even as the French were retreating, one of the Clito’s supporters, a Norman knight named William Crispin, spotted Henry who had dismounted. Crispin ran at Henry, raised his sword and aimed a blow at the King’s head. But the sword hit the collar of Henry’s hauberk (chainmail shirt) and drew no blood. Before Crispin could attack again, Roger of Clare struck him down and took him prisoner.

Having dealt with the French, Henry suppressed troublesome nobles in England and then came to an arrangement with the Church. He had now done everything possible to secure his position as king. His remaining concern was to ensure the succession for one of his children.

Henry had two children with Edith, or Queen Matilda as she came to be known: Matilda and William. There may have been two more children: Euphemia and Richard, both of whom died at an early age. The crown seemed to be destined for William. It was not to be.

In November 1120, the court was returning to London from Normandy. As King Henry was preparing to board ship, the captain of a new vessel named the White Ship begged Henry to cross the Channel with him, the captain claiming that his father had carried William the Conqueror to England in 1066. Henry was not interested, he wanted to travel on his own ship; but he said that his son, William, would travel on the White Ship. By the time the White Ship started its voyage, it was dark and everyone on board was totally drunk. Shortly after leaving Barfleur,theWhiteShipstruckasubmergedrockandwasholed below the water-line. The story is that William escaped in a small boat, later returning to the sinking vessel to rescue one of his illegitimate half-sisters, the Countess of Perche. Unfortunately, so many other people jumped into the small boat that it sank, and everyone in it drowned, including William.

Apparently, King Henry’s nephew, Stephen, had been on the White Ship, but had disembarked just before it set sail as he was suffering from diarrhoea. Lucky man; Stephen would take advantage of his ‘luck’.

William’s death left Matilda as Henry’s heir, and there would be no sons to take priority unless the King remarried, for Queen Matilda had died in 1116. Princess Matilda was a haughty, argumentative woman, but there was a greater problem. At the age of twelve, Matilda had been married off to the 32-year-old Holy Roman Emperor King Henry V, and she had spent most of her life in Germany, having been sent there to prepare for her marriage when she was only nine. If she became Queen of England, the Holy Roman Emperor would become king, and England would in effect become part of Germany. That was unacceptable.

Desperate for an alternative to Matilda, there was a movement among some of the barons to promote William the Clito to be the next king. To counter this, Henry began to advance the candidacy of another nephew, Stephen, the son of Adela, Henry’s favourite sister. Then, in a frantic effort to provide a new male heir, Henry married Adela of Louvain. It was in vain; despite Henry’s impressive record, there would be no children.

The situation became less complicated in 1125, when the Holy Roman Emperor died leaving no children. His widow Matilda returned to England, where she was grudgingly accepted as Henry’s heir by the barons. She was then, at the age of 26, forced to marry the 14-year-old Geoffrey, son of the Count of Anjou. That only created a new problem because the Norman barons did not want to be ruled by Angevins, their traditional enemies. But they lost their alternative heir in 1128, when the Clito died of wounds received in battle.

Next, Matilda quarrelled with her husband and went to live in Normandy. So Henry recalled her to England, where she succeeded in making enemies of just about everyone. Aware of the difficulties with Matilda, Henry continued to assist his nephew Stephen in obtaining land and wealth to compensate for any shortcomings in his entitlement to claim the throne by heredity.

Then, in 1129, Geoffrey of Anjou succeeded to the title of count, and he demanded the return of his wife. Henry was only too pleased to see Matilda leave, as was the entire court. Matters developed two years later, when Matilda gave birth to a son, Henry Plantagenet. The succession was now assured, although the barons still hated Matilda and objected to her Angevin husband.

Almost an irrelevance, in 1134 Henry’s oldest brother, Robert, died in Cardiff Castle. As Robert left no surviving legitimate children, it did at least mean that Henry was truly entitled to the crown and Matilda was entitled to succeed him.

However, nothing ever went smoothly where Matilda was concerned. She again fell out with her husband, and she went to live in Rouen, her father’s principal town in Normandy. King Henry rushed there to see his grandson. Yet Henry’s pleasures would be few, as most of his time was spent arguing with his unpleasant daughter. The aged king seemed to have been badly affected by Matilda’s constant aggression.