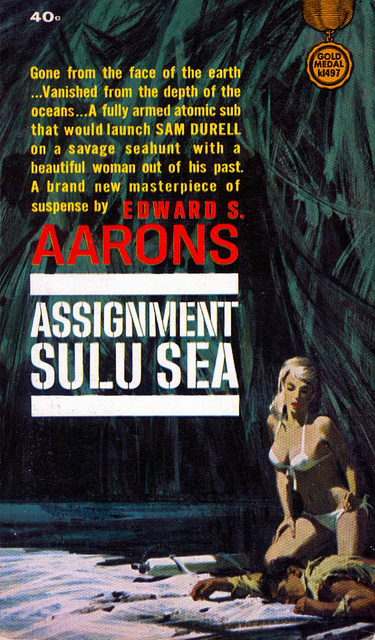

Assignment - Sulu Sea

Read Assignment - Sulu Sea Online

Authors: Edward S. Aarons

chapter one

HOLCOMB did not know how long he had been running or when

the sun came up, or when he fell at last in the sandy debris of coconut husks

and rotting palm fronds. He was afraid of the light. The screeching of the birds

and the grunting of a wild pig somewhere in the vine-shrouded wilderness beyond

the beach terrified him. He knew he was being followed. The sounds of the

birds and monkeys and pigs mingled with the sigh and crash of the surf of the

Celebes Sea on the beach. There was a kind of madness in the noise that

balanced the gibbering in the lurking shadows of his brain.

He made himself roll over and stared at the morning sky

through the palm fronds overhead. The sun was massive, red, swollen, as if it

had gorged on something. Like the red ball of the Jap battle flags on a

beach like this, Holcomb thought, on an island like this, in this same Pacific

so very long ago. Maybe everything was a dream, a reflection of the

barrage and the Jap kamikazes screaming down over the beach. Maybe he had

dreamed the twenty years in between, and here he was, back again in the reality

of war. But he knew it was no dream. The war was long over. There were no

Japanese hiding just inside the line of trees that leaned out over the littered

beach. All that was twenty years ago. And yet—

“Get up,” he said aloud. “Get up, stupid.”

His voice frightened him. It seemed louder than the crazy

screeching of the birds, the chattering of the monkeys. A smell of ozone filled

the air. There were huge combers, long, white, regular, rolling out of that

shallow tropic sea, out of that giant, swollen red crab of a sun. The light

blinded him. He wanted to weep. He got to his feet and reeled and fell and

looked back along the beach.

“Oh, you stupid bastard,” he said.

He had left his footprints there in the virgin sand,

reaching back as far as he could see in the misty dawn light. Back to where the

row of dead men lay, those fresh young men, those surprised faces, all laid out

so neatly, each one with a bullet in the nape of the neck, tearing away

vertebra and spinal cord and snapping, with a single blow, the slender,

precious thread of life. All those innocent faces, in such a neat row—!

“Move, stupid,” he told himself.

He could not remember when he had eaten last, and he looked

around for a fallen coconut, but when he found one he did not know how to crack

the massive husk that hid the meat, and after he spent some precious minutes

smashing it, with little effect, against the bole of a palm tree, he heaved it away

with a curse and gave up all thought of breakfast.

He ran a little and walked a little. He went through the

very edge of the surf, feeling clever now, letting the sea Wash away his

footprints. The ocean was tepid. The heat was building up fast. Of course, they

would know he hadn’t struck inland, into that tangle of jungle and mountain.

They‘d dog him along the beach, coming in a jeep, perhaps, or in a boat along

the outer reef, watching for him with binoculars as he reeled and staggered and

flapped his arms like a crazy scarecrow on a crazy beach, drowned in the heat

of a crazy Pacific island.

He had no idea of the name of the place, but he knew those

mountains, floating in violet haze far, far over the horizon, were on the

mainland of Borneo. Sabah? Brunei? The skipper had been surprised, sure enough.

Had they gone ten miles or fifty, off course? He knew this was the

Tarakuta Group, half submerged in the shallows between the Sulu and the Celebes

Seas, a forgotten cluster of tropical mud heaps off the Borneo coast, beloved

only by the Dyak aborigines in the mountains, the Hakka Chinese who worked the

tin sluice mines, and the Dutch and English colonists who had taken over the

old Sultanate of Pandakan, capital city of the Tarakutas. All right. So he had

to be on one of the Tarakuta Islands, somewhere off that distant, troubled

coast of Borneo. But there were hundreds, maybe a thousand of them. No one

really knew. They came and went, some of them, in the leaden sea.

Come on, keep walking, keep—

He was suddenly tumbled over by a comber, because he had

strayed too far from the foamy edge of the surf where little crabs scuttled out

of his way, and this comber had smashed at him out of the blue. It grabbed his

legs and tried to suck him out where the water was deep and he would quietly

drown.

Well, what was so bad about drowning?

For that matter, What was so bad about a quiet execution, a

single shot in the back of the neck to blow all your years into darkness? But

they were only boys, Holcomb, and you were only a boy when you were a Marine

and fought the laps around here, pushing them off? Borneo. You’re middle-aged

now, you’re partly bald and in your middle forties, and you just don’t have it

any more. If you try to run too long, something is just going to snap and break

in your chest, and that will be the end of it.

Well, he wouldn’t mind that, either. He began to giggle,

thinking that if they ever found him, they’d call him the original wild man of

Borneo.

There was just one thing about it all.

Somebody had to know the truth. Somebody had to be told what

had happened to those young boys and the skipper and that beautiful prize

package of a boat, the new 727.

Somebody had to be warned.

“What happened?” Holcomb asked aloud. “How did they do it?”

He didn’t know. None of them had known. Before they knew

what it was all about, what kind of jam they were in, it was too late. And the

boys went down like a row of dominoes, ka-pow! ka-pow! ka-pow! as fast as the

executioner could walk along behind them as they stood with their ankles and

wrists tied, and wondered if it could really be happening

to them.

He felt exhausted. The sun was hot now. He was surprised to

see how high it had climbed in the sky. Ah, the South Sea idyll, the rows of

coconuts, the gentle breeze, the surf, the blue Pacific! It stank. The

vegetation was rotten and the sea threw up, lite vomit, the dead bits and

pieces of fish and crab flat the sea scavengers had missed. And

they never told you about the noise of the birds and the monkeys and the crash,

crash, crash of the surf. Enough to drive a man crazy.

He fell down and lay with his face in the wet sand. The sea

washed o\'el' his leg, sighed away, washed in again. He wanted to sleep. But

every time he thought of the neat row of dead boys’ faces, he wanted to cry.

Boys from Iowa, or Philly; boys from Boston and Atlanta. Kids, all of them.

They had regarded him as an old man. But he was only forty-seven. He didn’t

wear a uniform, either. Maybe that’s why he had felt a little apart from them.

They knew he was O.N.I. Maybe they snickered about it. What, they must have

asked, was he looking for? Spies and Reds in the torpedo tubes? In the nuclear

engine room? Uncle Sam didn’t mind Wasting money, sending all those technicians

around the world on a joy ride.

Except that they hadn’t gotten around the world. From San

Diego they had gone to Honolulu and then come arching down across the big,

wide, beautiful blue Pacific, and then they had headed through the little

independent sultanate of the Tarakuta Archipelago, off Borneo. Yesterday they

surfaced and—and—

“Get up, Pete,” he told himself. “Please get up, or they’ll

catch you. They know you’re missing now. They’ll come after you like bats out

of hell.”

If this had been left to some Beverly Hills scenarist,

Holcomb thought. he’d have been rescued by now by a bevy of smiling,

pearly-toothed, gorgeous-breasted and scantily clad Polynesian beauties, all

just dying to slip into the bush with the great white stranger and heal his

wounds with love.

But he hadn’t even seen the proverbial Borneo wild man;

since ten o’clock last night, he hadn’t seen a soul. Nothing but these damned

birds and monkeys and pigs grunting and gulls screaming and the surf hammering

. . .

A shadow fell upon him.

He had known fear at times, in his life, but never anything

like the terror that seized his heart and squeezed the breath out of him with

one giant Wallop. He wanted to burrow into the sand and vanish. He wanted to

snap his fingers and suddenly just not be here. But this was not the

place or the age for miracles.

A toe prodded him, and it touched him just where his rib had

been cracked or broken—he didn’t know which—when he climbed over the palisade

to escape last night. He heard a scream of pain and knew it came from his

throat and could not believe it. When he rolled over, his hand closed

convulsively on a smooth piece of driftwood. He felt its weight and licked his

lips in cunning.

All right, he thought.

He looked up.

This was no man Friday for a castaway Robinson Crusoe, he

decided. The shadow of the man blotted out the hot morning sun. It even blotted

out the screeching of the birds and the thunder of the surf. It looked black

and enormous against the cobalt blue of the Celebes sky.

“You hurt, man?”

English, yet, Holcomb thought. He digs me, man.

“Yeah,” he said. “I’m hurt.”

“You look funny. Where you from, man?”

“The

Jackson.

”

“What?”

“The United States nuclear submarine

Andrew Jackson

, you dig?‘ Holcomb

And with a great effort and a lurch, he lunged to his feet and swung the

driftwood club at the black shadow looming over him.

At the

moment, he saw

the look of utter surprise and consternation on the black man’s face, under the

broad brim of

woven straw hat. The man

wore old blue denims, faded white

salt

and sun, straw sandals, and a dazzling

whlte

, clean

skivvy shirt. He saw with horror that there was standard U.S.N. stenciling on

the skivvy shirt, Somebody J,K. MM2/c— and then his club crunched down on the

man’s skull while, at the same moment in complete reflex, the stranger

swung his machete.

Holcomb hadn’t seen the knife at all.

He felt the Jolt on his wrist and arm as the heavy driftwood

smashed through flesh and bone and cartilage; and at the same moment, as if it

happened to someone else, he felt the

thunk

!

of the

razor-sharp coconut knife cut his flesh, cut through his shoulder and

muscle, hissing like a butcher’s blade. He staggered, fell to one knee, saw

blood gout to the sand in a great, rich splash, soaking in and turning black

almost at once. The world reeled and tumbled around inside head. He heard a

groan and a great screeching of the birds in the nearby jungle and the man in

blue denims began to cry out something in a language he could not understand.

Maybe nobody would understand it, ever, because he was bleeding from nose and

ear and mouth, thick, viscous blood that looked mortal, and there were funny

little spasmodic kicks and twitches to his legs as he lay on his back on the

sand.

Holcomb forced himself to stand erect. The beach swayed and

reeled under him. He staggered, caught himself.

“Any more of you out there?” he shouted. "Come on, come

on, let’s have it now!”

His voice was a hysterical cry in the wilderness of sun and

sea. He looked down at the big black man. The machete was bloody on the sand.

He picked it up. He looked at his left shoulder and shuddered. He could see

where the blade had sliced right through the meat of muscle and tendon to the

white, shiny, gristly bone. It was hard to believe he was looking at his own

tender, precious flesh. He was bleeding badly, and he became frightened

by it, wondering how much blood he could lose before he fainted.

“Hey, man,” he said to the stranger he had felled.

The black man groaned and muttered in his own language.

“Hey, man, didn’t they send you after me?" Holcomb asked.

The other's legs twitched and were still.

“You dead?” Holcomb asked.

The black man said, very clearly and distinctly: “Yes, you

killed me, stupid, and I only stopped by to help you.”

But his mouth didn’t move when he said it.

Terror seized Holcomb and he ran down the beach. Help me,

help me, God help us all, he thought. He flung away the driftwood club.

He thought of going back to get the machete, but he was afraid the dead man

might talk to him again, and he couldn’t stand that, because he knew he had made

another error, and he might have had help and spread alarm and rescued those

who weren’t already lying back there with their surprised young faces upturned

like flowers to the tropical sun. And the ship—yes, the ship—how could it

have happened? Trapped there, incredibly, even Captain Hardnose Johnson, that

tough old sea eagle, couldn’t believe it, couldn’t believe it had happened even

when that fat Chinese put a gun to his head and pulled the trigger—

Holcomb tripped and sprawled and landed on his wounded

shoulder and gave a screech of utter, mortal pain that echoed louder than the

surf and the birds. He fell in water, and choked and floundered and knew

he was drowning. He hadn’t even noticed the water ahead of him as he ran.

Strong hands caught his ankle and hauled him without

ceremony out of the warm, salt lagoon. Holcomb wasn’t sure if he were dreaming

or not.

A tall blonde girl, naked to her rich, creamy golden skin,

with eyes as blue as the Pacific sky, stood over him.

She was silent, and he saw by her face that he was dying.

He tried to speak. but nothing happened.

“Are you American?" the girl asked in English.

He tried to nod. He coughed and choked on salt water. He saw

that the girl wasn’t really naked. She wore the most vestigial bikini he had ever

seen, of a pale flesh color that was lost against the rich Polynesian

gold of her skin. She swung an oxygen tank and skin-diving flippers in one

long, delicate hand. She was the most beautiful, the most unbelievable creature

he had ever seen.