Aster Wood and the Lost Maps of Almara (Book 1)

Read Aster Wood and the Lost Maps of Almara (Book 1) Online

Authors: J. B. Cantwell

Excerpt from The Book of Leveling

Copyright © 2014 by J. B. Cantwell. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used, reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher, except where permitted by law, or in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, contact

[email protected]

.

ISBN:

978-0-9906925-0-8

Sign up for the J. B. Cantwell mailing list and pick any book by J. B. Cantwell for FREE!

One of the most helpful things you can do for any author is to leave an honest review. Please leave a review of

Aster Wood and the Lost Maps of Almara (Book 1)

For Evan and Zoe

My little travelers

Special thanks to:

Katharine Evans

for telling the truth

Brent Taylor

for keeping me going

and

Brian Cantwell

for always believing

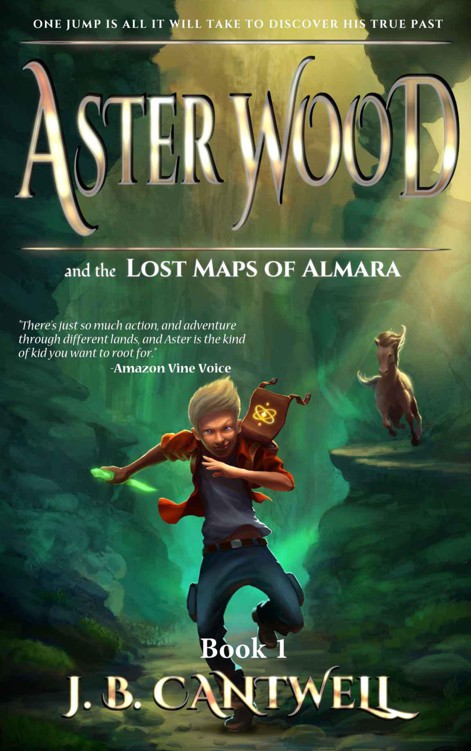

Cover art by Ken Tan

We barreled down the dirt road to my doom.

The mud-yellow farmhouse came into view behind the tired, crumbling barn. Our car blew by the bare cornfields that lined the narrow drive. I looked over at my mom, but her gaze was set stubbornly on the road.

I had wanted an adventure. But it wasn’t meant to be.

I didn’t want to go. I mean I

really

didn’t want to go. I had tried every trick I could think of to get out of spending the entire summer at the old lady’s farm. But Mom hadn’t been swayed a single millimeter by my whining, my yelling, or my threats to purposely flunk out of seventh grade next year if she didn’t send me somewhere, anywhere, else.

The whole situation was colossally unfair. She was unloading me during the only time of the year I might actually be able to do something normal, or even make a genuine, real-life friend. And friends were hard to come by for a kid like me. An inept, diseased heart had resulted in near total rejection by the kids in our section of the city. I had to be careful, never knowing when the ticking bomb in my chest would decide to explode, ending my pathetic existence. I sat on the sidelines, year after year, as the other kids played on the yard, made friends, ran free.

Fragile

, some adults might call me.

Freak

was the word the other kids would use.

I looked out the window as the fence posts slipped by. The openness of the land took my breath away, despite all my protests about being dumped out here. Dense, gray clouds billowed far away along the horizon, threatening the empty fields below. At least it was a relief to see the sky. I always felt so closed-in in the city, with its giant buildings shooting up on every side, blocking out the sun. Here there was nothing in my way; I might even be able to see some stars, something I never saw at home. I should have been happy; it was better than being stuck in the city, which would be wickedly hot come July. But I watched my mom’s eyes scrutinize the dry, cracked dashboard of the borrowed sedan as we sped along, and I was miserable instead.

I had begged her to send me to camp. They had camps, even now, even for sick kids; I had seen them on the snippets of news I pretended not to watch over her shoulder. They were in some of the last places we could go to visit nature, high up in the mountains above the acid haze. Hot sun would pink our skin during the day. And at night, an unpolluted view of the sky would reveal the cosmos winking down from above. Right now I could be paddling across a lake with some other ailing, misfit kid, all my efforts focused on trying not to tip the boat.

Instead I was strapped into the burning-hot passenger seat, all my efforts focused on not screaming in frustration. We didn’t have money for camp. I knew this, but knowing it didn’t help.

Grandma either heard the car coming down the drive or smelled the dust in the air, because she was standing in the doorway when we finally pulled up to the front of the house. Her belly, wrapped in a faded, flowered apron, preceded her down the porch steps as she walked out to meet us.

I didn’t mind the old lady, really I didn’t. But as my eyes took in the abandoned farm through my dusty window, I couldn’t help but blame her for her part in my summer imprisonment.

Mom unbuckled her seatbelt and opened the door.

“You coming?” she asked, eyebrows raised.

I glared back at her.

She huffed, and then hauled herself out into the hot, sticky summer air. I could hear the loud buzzing of cicadas through the door of the car even after she slammed it shut.

Grandma waved at me as she hugged my mom. Then Mom said something under her breath and they both turned to stare. I sunk deeper into my seat, trying to burrow into the quickly warming pleather. There they stood, plotting a way to make me comply, and I fumed hotter than the fast-rising oven-temperature of the car interior.

They talked for a few minutes, giving me a chance to give in, but eventually Mom resorted to the only strategy she had left. She marched up to the car, opened the passenger door and commanded, “Out.”

I climbed out of the car and stood in the spot her finger had been pointing to. She pulled out my shabby suitcase from the back seat and stood it next to me, then gave me a hug I did not return.

“Love you, kiddo,” she said as her fingers knotted in my shaggy hair. “Be good.”

“Bye,” I groaned.

“Oh, Aster,” she said, taking my face in her hands. I looked up miserably into her pleading eyes. “It won’t be so bad. Maybe there are some kids around here that you can hang out with.”

Kids?

Out here? Was she nuts?

“It’s only eight weeks,” she said.

“Eight weeks,” I replied blankly.

I turned to face the house. Grandma smiled. I walked up to her, dragging my suitcase behind me over the cracked dirt. Despite my efforts to grimace, I couldn’t help but melt a little bit at the sight of her. She opened her arms and I relented, letting her give me a big, squishy hug.

Behind me the car sputtered back to life. I turned as Mom put it in drive and rolled out of the driveway. Once she was clear of the big, dead tree that stuck up in the middle of the flat dirt lot, she hit the gas, leaving a cloud of dust where the road had been, and raced off to the airport.

I was officially abandoned.

I unloaded my suitcase up in the guest bedroom and looked around the sad, stuffy room. Wallpaper peeled from the corners, and an old clock sat still and powerless on the bedside table. A single fly buzzed up against the window, trying helplessly to get out.

I knew Mom didn’t have a choice but to work. She had spent years struggling to pay the rent, on top of the medical bills, on her own after my dad ditched us. He hadn’t made it through the “hospital days,” leaving around the time that all my heart problems started. Mom had stayed close with Grandma, which I guess was lucky considering that she was my dad’s mother, not hers. They had sat together during the long hours in the hospital waiting room after he took off.

When I was born my heart had a tiny hole poking right through its middle. It hid, undetected by doctors, until I started having trouble breathing at school. I overheard Mom crying on the phone one afternoon, a few weeks after my first surgery, telling someone on the other end that it was common for couples with sick kids to split up. She hadn’t seen me peeking around the corner until the phone call ended. She tried to reassure me, as she wiped the tears from her face, that his leaving wasn’t my fault. I was five.

He moved out of our city. He sent birthday cards. At least, some years.

Mom had already stopped listening to the specialists when they got to the part of assuring her that, after treatment, I would be able to have a normal childhood. She had different ideas in mind to protect me, no matter what the doctors said. From that point forward I was pretty much held under lock and key. She was forever worried that I would fall down dead if I so much as jogged across the schoolyard. Of course, I was scared, too. Years of doctors and hospitals would be enough to make anyone think twice before joining in the athletics offered at school, but it was the difficulty I often had breathing that really kept me in line. The tightness in my chest was a constant reminder:

don’t push too hard.

I looked out the small, dirty window at the remains of the fields below. The now unused farm tools lay in piles, rusting in the mud as the earth slowly swallowed them up. Grandma had continued trying to farm, even after most other people had packed it in and left. She used to have animals on the property like horses and chickens and even a pig or two at one point, but now the barn sat abandoned. I had a vivid memory, from before I got sick, of riding the old draft horse around the place with nothing but a lead rope and a fistful of mane to keep me from the seven-foot fall to the ground. It had been thrilling and terrifying at the same time, and I had wailed when they finally tore me from the big brute’s back.

All the animals were long gone now, though where, I had no idea. But Grandma had stayed on. She had said that she just couldn’t stand to leave the farm, no matter what dangers the rains brought. She traveled into town once a month to pick up a box of supplies, and she grew a vegetable garden out back, covered by a clear arch of plastic sheeting. But most of us, people who didn’t want to take chances with the weather, lived inside the protection of the cities.

“Hey Aster.” Her rickety voice surprised me, and I whipped around. “Do you have what you need up here? I thought you might want to come on down and watch my shows with me this afternoon.” She looked at me piteously.

“Thanks, Grandma,” I replied. “Maybe later.”

She eyed me cautiously, as if she was trying to determine how to dismantle a not-entirely-lethal bomb.

“Alright, hon,” she said finally, pushing her glasses up onto her nose. “You go ahead and get settled in.”

While I looked at her I secretly wondered, how old

was

she? Eighty-five? Ninety? I had never asked, and I had never really given it much thought before now. It was amazing she had survived so long out here, all alone. But something in her tired eyes told me that I could expect little excitement from her. She turned and walked unsteadily back down the staircase.

As the afternoon passed, the hot sun was slowly covered by thick thunderclouds, and the bedroom gradually darkened. After I finished unpacking I flopped down onto the squeaky, lumpy mattress.

I lay back into the musty pillows as thunder boomed in the sky above and tried to come up with something to do. The pelting of rain began to beat against the window. No going outside now. I watched the drops slide down the rippled glass and rolled over, caught up in my misery. I considered screaming into my pillow just for something to do, and I was just starting to jerk it loose from underneath my head when I heard it.

BOOM.

The walls rattled around me as the sound shuddered through the house. I sat bolt upright in my bed. Was that lightning?

BOOM. BOOM. CRASH.

I jumped off the bed, alarmed. What on earth had that been? As I walked out of my room and into the hall I could hear the sound of Grandma’s quiet snore from the top step; she hadn’t heard the sound. The theme song of a forgotten primetime favorite whistled out of the set. So the power was still on, then. It couldn’t have been lightning on the rod fixed to the roof of the house or the power would have gone out for sure. What had it been?

I looked around the hallway, but it was empty. The noise had come from

above

.

A short, dangling string hung down from the ceiling at the end of the hall. I had never been into the attic before. I tiptoed along the creaky floorboards, grabbed at the string and yanked hard. As the door squeaked open, a ladder unfolded. I carefully placed the bottom rung on the hallway floor and started to climb.