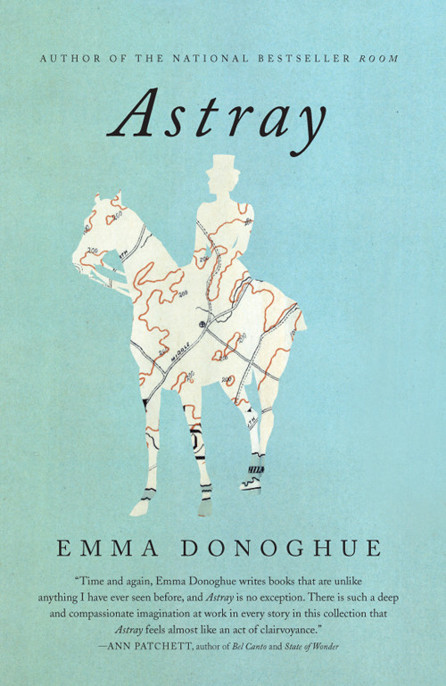

Astray (23 page)

Authors: Emma Donoghue

Children don’t decide where to live, or what ventures are worth the risk; they get sent around the world as helplessly as parcels. While Lily May Bell, aka Mabel Bassett, zigzags

her way west in “The Gift,” both her birth mother and her adoptive father repeatedly stake their claim to her in correspondence with an intimidating bureaucracy. As a mother, I grit my teeth to think of Sarah losing her child forever because she was once poor. As a mother, again, I defend the Bassetts when they insist on the primacy of their de facto, hands-on parenting. So “The Gift” is an epistolary duet between rivals who never address each other directly, because I could think of no other way to honor their bitterly irreconcilable demands to be the girl’s family.

Sometimes settling in seems almost impossible for emigrants, especially if their destination keeps failing to live up to the Promised Land of their imagination. The Puritans, for instance, soon discovered in the “virgin territory” of New England all the horrors they thought they’d left behind in Europe. Like “stray,” the word “lost” has always had a moral meaning as well as a spatial one. The ultimate punishment, in Puritan communities, was to be banished, sent into a literal wilderness that matched what they saw as the spiritual wasteland of the sinner’s heart. “The Lost Seed” is the opposite of a story I meant to write: its inverted mirror image. For years I was intrigued by an odd incident in which two women in Massachusetts were charged with being “lewd” together on a bed. But when I tracked down the source, what began to fascinate me was not the accused but their accuser. Fiction does that, in fact that is one of its most radical strengths; it disrupts the writer’s sympathies as much as the readers’.

A particularly liberating thing about historical fiction is

that people rarely guess how autobiographical it can be. I wrote “The Lost Seed” as a shell-shocked immigrant during my first winter in Ontario, when, exactly as Berry remarks, the icicles hung over my front door like swords pointed at my head. “Vanitas,” by contrast, came out of a trip I made through rural Louisiana. In my story, Aimée Loucoul’s whole French Creole clan define themselves by reference to the home country for which they yearn; the cult of Frenchness is their true vanity. If travel is a stay-at-home girl’s fantasy, nostalgia for a lost Eden can be a family’s blight.

Whether in the form of military campaigns or the consequent flight of refugees, war is the root of many journeys. For “The Hunt,” a story about the contemporary-seeming topics of child soldiers and rape as a war crime, I went all the way back to 1776. When you are uprooted from your familiar landscape, and from your home culture, how can you hold on to your sense of what’s right? By telling the story of this fictional boy and girl during a terrible historical moment, I wanted to ask about what it means to be (paradoxically) an unpaid mercenary, sold into service in a far country; about the ethics of obeying orders; about victims who have themselves betrayed others.

Sometimes it is someone else’s journey, someone else’s decisions, that leave a thumbprint on your life. What haunts me about Minnie Hall in “Daddy’s Girl” is the idea of a life lived in a strong character’s turbulent wake; Minnie’s path is shaped by her father’s complicated prior journey. Like Mabel in “The Gift,” Minnie has to live with

a parent’s commitment to a secret; she will never know where she came from, nor where Murray did, nor what lay behind Murray’s decision to cross over the highly policed border of sex. So often these tales of emigration turn into tales of transformation, as if changing place is just a cover for changing yourself.

The sculptors in my last story, “What Remains,” have lived and worked together all their lives until the moment Queenie goes ahead of Florence, straying across the line between clarity and confusion. As in “Counting the Days,” this is a story about a couple divided, not by space this time but by a more painful alienation. Florence tries to bridge that terrible distance by means of love and memory, reckoning both the sum of what their long shared life amounts to and the dwindling total of “what remains.”

Her task reminds me of my own. When you work in the hybrid form of historical fiction, there will be Seven-League-Boot moments: crucial facts joyfully uncovered in dusty archives and online databases, as well as great leaps of insight and imagination. But you will also be haunted by a looming absence: the shadowy mass of all that’s been lost, that can never be recovered.

Unease. Wonder. Melancholy. Irritation. Relief. Shame. Absentmindedness. Nostalgia. Self-righteousness. Guilt. Travelers know all the confusion of the human condition in concentrated form. Migration is mortality by another name, the itch we can’t scratch. Perhaps because moving far away to some arbitrary spot simply highlights the arbitrariness of getting

born into this particular body in the first place: this contingent selfhood, this sole life.

Writing stories is my way of scratching that itch: my escape from the claustrophobia of individuality. It lets me, at least for a while, live more than one life, walk more than one path. Reading, of course, can do the same.

May the road rise with you.

Emma Donoghue

London, Ontario

2012

“Man and Boy” was first published in

Granta

(the Fathers issue, ed. by Alex Clark, December 2008).

“The Widow’s Cruse” first appeared in

One Story

(August 2012).

“Counting the Days” was first published in

Phoenix Irish Short Stories 1998,

ed. by David Marcus (London: Phoenix House, 1998), and broadcast on CBC Radio, May 2001.

“Snowblind” was first published in

The Faber Book of Best New Irish Stories,

ed. by David Marcus (London: Faber, 2007).

“The Body Swap” first appeared in

Princeton University Library Chronicle: Special Issue on Irish Prose

(2011).

Earlier versions of “The Lost Seed” were broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in May 2000 and published in

Groundswell: The Diva Book of Short Stories 2

(London: Diva Books, 2002).

“Vanitas” was first published in

Like a Charm: A Novel in Voices,

ed. by Karen Slaughter (London: Century and New York: William Morrow, 2004).

“The Hunt” first appeared in

The New Statesman,

January

2011, and was short-listed for the 2012

Sunday Times

EFG Private Bank Short Story Award.

A slightly different version of “Daddy’s Girl” was first published in

Neon Lit: The Time Out Book of New Writing,

ed. by Nicholas Royle (London: Quartet, 1998), and broadcast on BBC Radio 4, May 2000.

“What Remains” was first published in

Queens Quarterly

(spring 2001) and was shortlisted for the Journey Prize.

I would like to express my appreciation to all these editors, especially the late, great David Marcus. Also to Susan L. Johnson, whose essay “Sharing Bed and Board” sparked two of these stories, and to Scott Anderson at Sharlot Hall Museum and Christopher Dears, for going out of their way to help me with research inquiries for “The Long Way Home” and “Daddy’s Girl” respectively.

Born in Dublin in 1969,

EMMA DONOGHUE

is an Irish emigrant twice over: she spent eight years in Cambridge doing a PhD in eighteenth-century literature before moving to London, Ontario, where she lives with her partner and their two children. She also migrates between genres, writing literary history, biography, stage and radio plays as well as fairy tales and short stories. She is best known for her novels, which range from the historical (

Slammerkin, Life Mask, The Sealed Letter

) to the contemporary (

Stir-fry, Hood, Landing

)

.

Her international bestseller

Room

was a

New York Times

Best Book of 2010 and was a finalist for the Man Booker, Commonwealth, and Orange prizes. For more information, go to www.emmadonoghue.com.

Visit www.AuthorTracker.com for exclusive information on your favorite HarperCollins authors.

“Emma Donoghue is one of the great literary ventriloquists of our time. Her imagination is kaleidoscopic. She steps borders and boundaries with great ease and style. In her hands the centuries dissolve, and then they crystallize back again into powerful words on the page.”

—COLUM McCANN,

author of Let the Great World Spin

“An entirely original work of art. I mean it as the highest possible praise when I tell you that I can’t compare it to any other book. Suffice to say that it’s potent, darkly beautiful, and revelatory.”

—MICHAEL CUNNINGHAM, author of

The Hours and By Nightfall

“Room is one of the most profoundly affecting books I’ve read in a long time. I read the book over two days, desperate to know how their story would end…. Room deserves to reach the widest possible audience.”

—JOHN BOYNE, author of

The Boy in the Striped Pajamas

“Remarkable…. Both gripping and poignant, it’s a tribute to human resourcefulness and resilience in extremity, and a stirring portrait of a mother’s devotion.”

—

Toronto Star

“Thrilling and at moments palm-sweatingly harrowing…. A truly memorable novel.”

—

The New York Times Book Review

“An astounding, terrifying novel.”

—

The New Yorker

Room

Inseparable: Desire Between Women in Literature

The Sealed Letter

Landing

Touchy Subjects

Life Mask

The Woman Who Gave Birth to Rabbits

Slammerkin

Kissing the Witch: Old Tales in New Skins

Hood

Stir-fry

AUTHOR PHOTO BY NINA SUBIN

Astray

Copyright © 2012 by Emma Donoghue, Ltd.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

EPub Edition © AUGUST 2012 ISBN: 978-1-443-41081-6

Published by HarperCollins Publishers Ltd, by arrangement with Little,

Brown and Company, a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

FIRST CANADIAN EDITION

These are works of fiction based, to a greater or lesser extent depending on the story, on historical incidents. Certain details have been changed and many invented.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in reviews.

HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

2 Bloor Street East, 20th Floor

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

M4W 1A8x

www.harpercollins.ca

Lines from

The Aeneid of Virgil

by Virgil, translated by Allen Mandelbaum, copyright © 1971 by Allen Mandelbaum. Used by permission of Bantam Books, a division of Random House, Inc.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Donoghue, Emma, 1969–

Astray / Emma Donoghue.

Short stories.

ISBN 978-1-44341-079-3

I. Title.

PS8557.O559A88 2012 C813’.54 C2012-903035-X

RRD 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Australia

HarperCollins Publishers (Australia) Pty. Ltd.

25 Ryde Road (PO Box 321)

Pymble, NSW 2073, Australia

http://www.harpercollinsebooks.com.au

Canada

HarperCollins Canada

2 Bloor Street East - 20th Floor

Toronto, ON, M4W 1A8, Canada

http://www.harpercollinsebooks.ca

New Zealand

HarperCollinsPublishers (New Zealand) Limited

P.O. Box 1 Auckland,

New Zealand

http://www.harpercollinsebooks.co.nz

United Kingdom

HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

77-85 Fulham Palace Road

London, W6 8JB, UK

http://www.harpercollinsebooks.co.uk

United States

HarperCollins Publishers Inc.

10 East 53rd Street

New York, NY 10022

http://www.harpercollinsebooks.com