Augustino and the Choir of Destruction

Read Augustino and the Choir of Destruction Online

Authors: Marie-Claire Blais

Augustino and the

Choir of Destruction

ALSO BY MARIE-CLAIRE BLAIS

FICTION

The Angel of Solitude

Anna's World

David Sterne

Deaf to the City

The Fugitive

A Literary Affair

Mad Shadows

The Manuscripts of Pauline Archange

Nights in the Underground

A Season in the Life of Emmanuel

Tete Blanche

These Festive Nights

The Wolf

Thunder and Light

NONFICTION

American Notebooks: A Writer's Journey

Augustino and the

Choir of Destruction

_______________________________

MARIE-CLAIRE BLAIS

Translated by Nigel Spencer

Copyright © 2005 Les Editions du Boreal

English translation copyright © 2007 House of Anansi Press

AAll rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Distribution of this electronic edition via the Internet or any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal. Please do not participate in electronic piracy of copyrighted material; purchase only authorized electronic editions. We appreciate your support of the author's rights.

This edition published in 2012 by House of Anansi Press Inc.

110 Spadina Avenue, Suite 801

Toronto, ON, M5V 2K4

Tel. 416-363-4343

Fax 416-363-1017

First published as

Augustino et le choeur de la destruction

in 2005 by Les Editions du Boréal

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Blais, Marie-Claire, 1939â

[Augustino et le choeur de la destruction. English]

Augustino and the choir of destruction / Marie-Claire Blais ; translated by Nigel Spencer

Translation of: Augustino et le choeur de la destruction.

Final volume in the trilogy: These festive nights, Thunder and light,

Augustino and the choir of destruction.

ISBN 978-1-77089-071-8

I. Spencer, Nigel, 1945â II. Title. III. Title: Augustino et le choeur de la destruction. English.

PS8503.L33A913 2007 C843'.54 C2006-903673-X

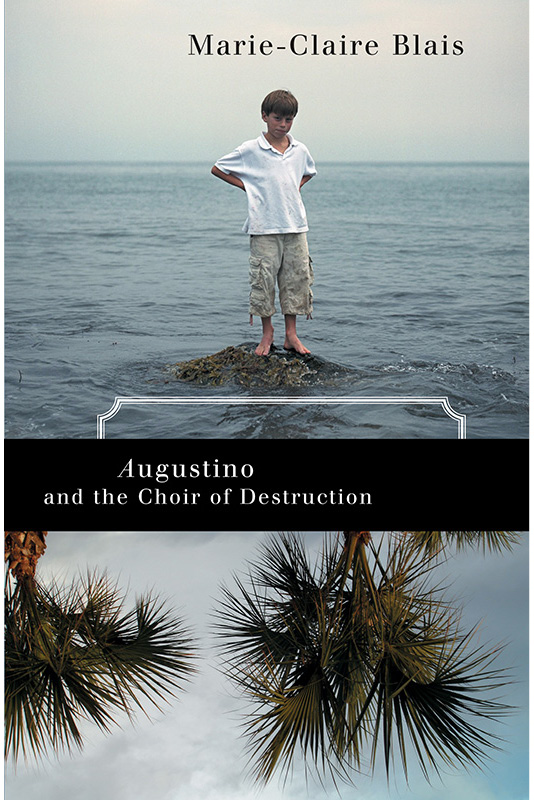

Cover design: Bill Douglas at The Bang

Cover images: (top) Ghetty Images, (bottom) Bill Douglas

We acknowledge for their financial support of our publishing program the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP).

For Christiane Teasdale

The longest voyage needs no trunks,

and what I give is all I have.

Take my gaze, rich in its poverty;

It's made from sky, warm air, cool water,

so ugliness can one day be washed.

Take my hands, so alive with caresses

and the rebellions that they've hatched.

Take my hair,

untameable,

it's always shouted.

Take my silence, my giddiness . . . the rest

is for the last great wave,

the first of the first tide.

â Georgette Gaucher Rosenberg, from

Ocean, Take Me Back

P

etites Cendres smelled with disgust, she said, the drunken man's breath on her lips and neck, as this stranger pinned her to the wall of the bar: stop, will you, you're going to suffocate me, what could she say to be safe, no one had any respect for her, the man who had arranged to meet her in the hotel at eight this evening and his strange accent had a heavy violence, a fleshy weight whose oppressiveness she had glimpsed, bald head she didn't like either, nor the baggy eyes of this stranger under his silver-rimmed glasses, leave me alone, Petites Cendres said again, thinking of how she had to drop by briefly at the Porte du Baiser Saloon where she danced every day for customers as dull as this one squeezing her waist and flattening her against the wall, she could see the pink wooden houses lit by the sun on Esmerelda Street and Bahama Street, a dog sniffing vainly for any trace of the owner who had abandoned it, why didn't he just head for the sea, at least there'd be some coolness, he probably hadn't eaten for days she thought, his colour, his colour was the same as hers too, not brown, not black, but at least if she didn't eat it was simply from lack of appetite, she had all she needed from the shade and the vented air in the Saloon, fed also by what had become her unfilled need, yes, the dog was a dark ochre colour like rust, just like Petites Cendres, nobody was going to feel sorry for him, too old, forty they all said, too late, the man was dragging her out into the street, and she was ashamed that everyone would see her now, hear her whimpering, leave me alone you kids, because that's what they called her, Ashley, hey Little Ashes . . . Petites Cendres . . . forty years old and you're teetering on the brink, laughing as they called out the numbers coming up in the Saloon that night, in their evening clothes and stiletto heels, coarse heavily built men, she thought, but they don't give a damn what happens to me, they'll see, they'll see later on, nobody gets respect at this age, nobody, and one of the boys who didn't have a wig, yawning on the sidewalk, no wig, just earrings and short, slicked-back hair, she noticed, he just thought it was funny, the john's tattooed arm across her throat, then he tapped the drunk on the shoulder, hey, loosen up on her a bit, will you, you don't want her to croak on us, do you, and the man shook himself out of his stupor and flung her onto the sidewalk like a rag, don't forget . . . be at the hotel by eight, girl, he said; that's it, show him you're a man yelled the bare-headed, kid with no wig, so are you a man, I'm the man that I am, the way the Lord made me, said Petites Cendres as he watched the bottom-feeder slouch away from him, yes, that's how he made you all right, said the kid with no wig, bit stuck-up aren't you Ashley, with those jeans so tight on your skanky ass, your black corset, the zits on your face, your plastic tits, aintcha got a little angel-dust for me while you're at it, it's a black silk corset, he said, and I am just the way I am, you get nothing from me, the kid with no wig went on, watch out for your john, he looks like a wrestler in the ring, get a load of that ox-neck of his, he'll beat you to a pulp, afraid are you, Ashley, come on and prove you're a man, then they all started laughing again, in their evening wear, Petites Cendres did not know if they were just indolent, mean or ferocious, he saw the sea glittering under an incandescent sun at the far end of the long, narrow street, on the shoreline of Atlantic Boulevard, any moment now that sun would burst into a ball of flame, a furnace to stifle the heart of Petites Cendres, his soul felt blood-raw, liquefied deep down inside him, in a pale, cold sea where the need that gnawed at him would break your heart, a fire burnt out, his heart, that dog should not have been there on Esmeralda or Bahama Street, hunger tottering on all fours, night-prowling around the Porte du Baiser Saloon where he just would not stop living despite all odds; in thunder and light, Lazaro launched his boat from the side of the wharf, thinking he would rather work at sea than be a student and live with his mother Caridad and those brothers and sisters of his, all of them born here of a man not his father, not even a Muslim, his mother had betrayed him by pardoning Carlos for his murderous act against her son, none of them, not one, knew who this Lazaro really was, sitting, hatching his revenge against Carlos, ready to kill him when he got out of jail, unless of course Justice did it for him, oh yes, maybe Justice would be fair and kill Carlos, then Lazaro would be recruited for some grander mission, and not only Carlos would disappear but all the others, Caridad the charitable who mangled the faith of their ancestors, her pardon was just a caricature of pity, there should be pity for no one, not Carlos or the others, from a grumpy fisherman resigned to working the sea with his hands, a student with no diploma, Lazaro would become someone, someone . . . who knows what, he needed a pitiless role, one to light a fire under the whole of the earth, he had written to his uncles and cousins, recruit me, I'll volunteer, be a missionary for some dark work, for he had known from childhood, hadn't he, that one day the earth would belong to the militant and soldier tribes alone, no more women, certainly none like his mother, Caridad â changing countries so they could unveil their faces and drive cars â none of these anymore . . . the sullen, strong-willed, dry and thirsty planet would be reserved for the young and angry, those destined to sensitive missions of martyrdom, thousands of them, unnamed and unnameable, candidates for suicide, flourishing in disordered ranks worldwide, staging attacks anywhere and everywhere â supermarkets in Jerusalem, hotels in New York â they would be heard if not believed, because of the panache of their murders, the toll rung by the belt-activated bombs they all would conceal under their clothes and in handbags, girls breaking off engagements and hiding mortar shells beneath folds of scarves, in bags, at store entrances, in stations, holding them so close to their own organs, these innumerable unnamed brigades alone would inherit the earth, bombs would be housed in their young and healthy bodies and holy terror would reign, oh yes, in whole cities, on tiled floors in cafeterias of Hebrew universities, where squads of nurses would lean over pools of blood â here seven people died â quickly wrap them in sheets just as quickly soaked in blood, and still gloved, the nurse would take the wheel and drive home to his family at night, something sticky still on his fingers . . . ah, he would say, may God have pity on this blood; in every town and village, on walls of homes and schools, there would be pictures of suicide-bombers with crowns of flowers, brigades of pious volunteers, nurses constantly on call and on the move to massacre-sites, gloved alike, and surgeon-like, who would say that blood is the seat of the soul, and like the kamikazes these new angels of death would become heroes subjected to a familiar ritual, here, in this cafeteria, where seven people died, and now the pile of bodies must be removed amid shards of glass, broken tables, and tomorrow it would be the same thing somewhere else, in a bar another woman would be sitting with her elbow on the counter, eyes open, glass in hand, a marbled statue in sudden death, tomorrow more streets and houses, tanks splitting the pavement, footsteps in the smoking dust of exploded houses, such was the world Lazaro had contemplated since childhood, or it might have been when his father Mohammed beat his mother before he was born, blows that came from a long way off, when his mother said, we must get away from Egypt, this country, this man . . . might there be still more streets and houses or gassy smells, smoke billowing from the sky, I'll get him, I'll get that Carlos one of these days, Lazaro said to himself over and over as he walked down Atlantic Boulevard, where the sun was red as it prepared to vanish into the sea, and the air was so sweet you'd think you were swallowing it and getting drunk; Lazaro waded barefoot through the sea, his body shaking with rage as he soaked his face and hair in the salt water, remembered Carlos, and heard a heavy flapping of wings, the sudden, troubled passing of a wounded pelican, frightened and desperately try to scoop up fish and stay alive, still lumbering awkwardly over the water, but seeming only to skim the hard surface of the waves with his beak, the sound of his one good wing racketing skywards; Lazaro climbed the stairs to a terrace and tried to get help for the wounded bird, thinking petulantly that his mother would have done the same, talking on and on as she did about respecting nature . . . Lazaro spotted the bird from the terrace, apparently staying close to shore, looking for shelter beneath a bridge, flying more and more lamely, and panicked now, the weakened pelican suddenly abandoned the protection of the shoreline and headed for open water, and Lazaro could no longer see the yellow-gold plumage of the bird's head, as though some malevolent fate had snatched the endangered bird away from him, and he felt a moment's anguish, this world of small and larger birds that could be seen in the wakes of boats, sailboats used by fishermen, and wasn't this after all the last domain which could still win Lazaro over with its vitality, its diversity and its courage in the face of an uncertain ocean, a world not yet reflecting a dark, deathly light like the mission he could not stop thinking about â avenging himself on Carlos or the militant action he wanted to carry out â when these thoughts of his future were frequently fleshed out and freighted with primitive foreshadowings, this majestic world of birds, for instance, he came close to fainting, he thought, and Mère, whose birthday they were celebrating, heard her daughter Mélanie saying to Jermaine's parents, oh, but Jermaine doesn't play with Samuel any more . . . before yes, but not now, he's a handsome young man whose Asian features resemble his mother more an more, but didn't he just spoil it all, thought Mère, by bleaching his hair blonde like that and making it stick straight up on his head, Mélanie was saying, women must learn to govern, we need a woman president, because when men are in charge they start wars, but Chuan replied that when women governed, they could be just as cruel and ambitious as men, think about those “enlightened despots,” said Jermaine's mother, like Catherine the Great they crushed an entire population of serfs and peasants under feudalism, entirely indifferent to the suffering of their people, and it's often been that way â even nowadays â oh, I don't mean you, Mélanie dear, we could never get enough of your sincerity in the Senate, but my husband, one of the first black senators ever elected, won't tolerate any talk of politics in this house, and now he's retired, he channels his protest through writing, often alone in the cottage over by the ocean there . . . just down the path and through the hibiscus from the house . . . he often phones me, and we talk several times a day, when I'm not off designing in Paris or Milan or Hong Kong, his real home is here on this island near his family, Olivier's not a nomad like me; Mère told Chuan how delighted she was by her house and everything she created by way of decoration, Chuan knew how to pare things down to their essential forms, and her houses in the Dominican Republic and here, facing the ocean, were as light as Thai cottages out on the water which reflected onto the white blinds of the living room, air wafting through the row of palm trees in the garden, luxuriance and weightlessness, Mère said, thinking neither of her daughter nor of Chuan to whom she addressed these polite words, but seeming to ask herself vague questions, or rather afraid to ask them, at almost eighty, she had made a success of her life, though what that meant for a woman she wasn't sure . . . on her deathbed with an insidious anaemia, Marie Curie had told her daughter Eve, “I don't want what you're going to do to me. I just want to be left alone,” and Mère too wondered what will they do to me when they see my right hand trembling, and some other things are not quite right, Mélanie, who notices everything, what will she do to me, I want to be left alone, her last words must be like those of the great apostle of pure science, “I do not wish it,” but it wasn't about to happen anytime soon, you never change, Esther dear, they always told her as she sipped her cocktail in the warm breeze, naturally, I still have plenty of time to think about all that, “Sleep,” Marie Curie had said as she closed her eyes, sleep. Yet Marie Curie was a woman of renown, the Mozart of science, Mère thought, but still, born a woman, she might not have thought her life a success, is it possible she left this world with doubts, saying over and over to her daughter that she wanted to be left in peace, not bothered any more, that this life was just too much, so many tribulations, so little grandeur, just too much to bear, she would die with the true scale of her work unknown, just to be allowed to sleep at last; might an accomplished life go hand-in-hand with success? Maria Sklodowska's childhood in Poland had not been especially promising, brothers and sisters dying around her of tuberculosis or typhus, very early on she became an agnostic and had to do without whatever support was not as solid as science, the disappearance of God, the loss of her parents . . . all this left her mind free and clear, Maria knew this, the straightforwardness of thought alone would yield rewards, no wandering across snowy fields, no sleigh rides for this little girl, perhaps the companionship of a dog in her study, wars and insurrections had drained the world of its blood, but through the dark emerged the thoughts of one who did not yet know who she was, she could not say with the authority of others before her, I am Darwin, I am Mendeleyev â their theories had penetrated her mind even before she knew who she was, what was success in life, born like Marie Curie, in Poland oppressed by the Russians, and no voting rights for women, in England or anywhere else, to discover as one grew older that academicians and intellectuals were imprisoned in Siberia, then to be swept up in an era of positivity when the emancipation of women would be justified, or to be assassinated for revolutionary politics like her

friend Rosa Luxembourg, whose young body would be found floating in a Berlin canal, what was success in life, wondered Mère, knowing how to design, plan and build harmonious coral pathways â as Chuan had done in front of her house â or being Rosa Luxembourg, the falterings, the failings bearing down on Maria's life, whether teacher or housewife, poverty ground people down everywhere, were the grumblings and ingratitude of others all she could ever expect? In this far-away Polish village, so alone in her mansard-roofed cottage that one had to get to it in winter by a stairway, she devoured literature and natural science, read in French and Russian, got up at five in the grey dawn, stuck doggedly to her physics and math books, still not knowing who she was, a failed schoolteacher, a creature petrified by the sheer concentration of all her faculties, waiting under that mansard roof for her father to send her money from home, and when none came, she sent her own salary to help her brother with his studies, in her isolation, Maria wrote to her family that she had no plans for the future, or at least such banal ones they were not worth mentioning, she would get by as best she could, and one day, so she wrote, she would bid farewell to this petty life, and the harm would not be great, neither Darwin nor Freud, just an ordinary being, it was the time of year when everything was frozen, the sky, the earth, there was revulsion against any physical contact, this too she felt, and why mend your clothes when there was no one to dress up for, nerves were the last thing alive under that ice and clothing and body and soul, all lying uncared-for beneath this deathless winter, the spark came from learning chemistry, though she had written her brother that she had given up all hope of ever becoming someone, failure, thought Mère, yes, the unbearable failure of every successful life, the ascetic face of Maria Sklodowska bent over her work and assembling so many pictures and voices that Mère no longer found her way through them, Chuan had taken her by the arm and was inviting her to meet the guests she called her European group, writers and artists newly arrived on our island: Valérie and her husband Bernard, Christiensen and Nora from even farther away â Northern Europe; of course, arriving in Paris was more stimulating for Maria than stagnating in her village, thought Mère, Chuan shouldn't have bothered to introduce her to all these charming people, she mused, she would never have time to get to know them, night began to dim everything, and nothing would remain of these hand-shakings or glances as they said I've heard a lot about you Esther, dear, and your daughter Mélanie with such wonderful children, Mère was thinking they should have left her in peace for the rest of this life journey of hers which seemed so short, or perhaps Paris shocked the austere Maria, so earnest she was for a city that, after so many fires, revelled in lightness of being, or perhaps she was afraid, then there was that annoying click of Augustino's computer, the picture of a hundred dolphins on the screen, carcasses rolled over by the waves and deposited on the white sands of an island in Venezuela, what had happened to provoke this mass suicide in just a few short hours, or what poison at the very depths had cheated them of their lives? Mère said to Augustino, turn that computer off, I can't stand it any more, Augustino, you don't seem to understand that an old lady just can't look at everything, there are things I do not want to see, and he had looked at his grandmother without understanding, it was the first time they had not got through to one another, she was always saying, please don't bother me, and yet yesterday he had done it constantly without her ever complaining once, I mean, who knows, in a few years you might be an intellectual or a philosopher, and your grandmother will read a book of your thoughts with pride, how many fingers could you count those years on, or how many hands, Augustino asked, his eyes suspicious under long lashes, well, right now you're only sixteen, she said as though she held his youthfulness against him, their social instinct and their psychic skills are more developed than ours, so why couldn't their ultrasound guide them, and why these multiple beachings on the white sands of l'île de la Tortue, can you tell me, Augustino, she once would have said to him, but her clouded blue eye stared at him as if to say, never mind, don't say a thing, what's the point, I don't want to know, they're just poor dolphins, one of many species that will soon cease to exist, and Augustino thought she hasn't answered my question about how many fingers for how many years, it must be because she doesn't believe they exist, she's taken so long to get old, and I may not have very long to become young, bottle-nose dolphins are very smart, Augustino had said, but they aren't suspicious enough of us, and they are often victims of our mistakes, who knows, repeated Mère, perhaps one day I'll read your thoughts in a book, she could not wish anything more distinguished for him, she thought, something Jermaine's parents could never say, because their son never even read a book, let alone wrote, sports cars were all he cared about, his father Olivier regretted that, yes, sports cars and those harmful video games, he had them all, and children developed the same indifference, lack of interest to the handling of massive war machines, engines of destruction that no longer make the slightest impression on them, at least, Mère thought, Augustino has no use for them, more restrained than Jermaine, he did not burst into his father's study, his intimate writing hideaway, in the morning and teary-eyed say, I love you, Dad, can you lend me some money or the car or both; Olivier, holding back a bit, asked his son once more, say you love me, is it true, you didn't write to me when you were at university, Chuan retold all these little events to Mère, my husband's very close to his family, she said, but he shuts himself up with his dogs too much and refuses to come out, he's the one I worry most about, it's depression that comes out in this paralyzing thoughtfulness, you know; Chuan suddenly fell silent, and Mère thought she could hear the world turning in her silence, it was un-intriguing tumult which took hold, every pore of the flesh was offered up, listening, lies and noise, and Mère said to Chuan, I know what your husband is feeling, but why don't you come and dance for us like last year, this year I don't dare do what is forbidden, Chuan said, I borrow a little of that ecstasy I criticize my son for taking, and as she listened, Mère thought how deprived of rest Marie Curie's life had been, even when she was only twenty-five, Maria shied away from amphitheatres and exam halls where she would be first, what a day it was for Maria, a woman, what a day it was when she came in first for the Physical Science degree, this reticent woman with nervous afflictions, and how she showed her joy despite her persistent fear of succeeding, of easy triumph, yes, Mère thought she heard the turning of the world with its bump and jolts within Chuan's silence, they might have spoken up, with all that's going on nowadays, for the earth and its inhabitants, she thought, whether it be surrender or death, perhaps people were aware that a minuscule part of the planet had been wiped out, still life had to go on, and even Chuan must have sensed that night it was her duty to dance, yes, singing and dancing had to go on whatever racket they made, turning the world on itself, or was it fair and sane to think this way beneath a deluge of gigantic explosions any sensate human being had got used to, however bored Jermaine had become by the on-screen manÅuvres of his demonic games, entire territories disappearing, the spectacles of huge structures crumbling, seeing them over and over, we no longer felt disturbed by them, these glimpses orchestrated by an invisible choir no longer troubled us, so now we had, it seems, been won over