Austerlitz: Napoleon and the Eagles of Europe (20 page)

Read Austerlitz: Napoleon and the Eagles of Europe Online

Authors: Ian Castle

Tags: #History, #Europe, #France, #Military, #World, #Reference, #Atlases & Maps, #Historical, #Travel, #Czech Republic, #General, #Modern (16th-21st Centuries), #19th Century, #Atlases, #HISTORY / Modern / 19th Century

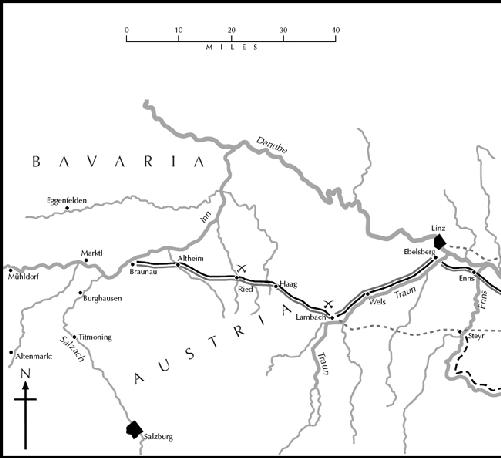

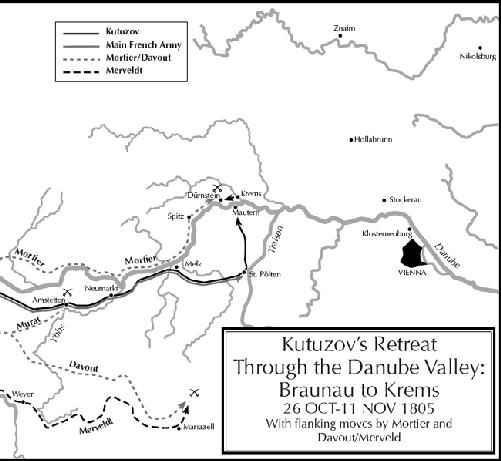

Kutuzov then began to make plans for the withdrawal of his army. Initially, he set his slow-moving wagons and artillery back down the Danube valley, giving them a chance to get ahead. He reformed his Russian troops in and around Braunau and prepared orders with Merveldt for Kienmayer to destroy the bridge over the Inn at Mühldorf on 24 October, and withdraw the following day through Braunau to occupy Salzburg with his 16,000 men, in order to protect the left flank of the army. Nostitz with his

grenz

infantry and 4. Hessen-Homburg-Husaren took a position at Passau, at the junction of the Inn and the Danube, to protect the right.

Back at Ulm, with the great drama of the surrender of the Austrian army complete, Napoleon quickly turned to more pressing matters: the defeat of the Russians. Right from the start, speed had been of the essence to defeat the leading Austrian force before support arrived from the Russians. Having disposed of those Austrians he now needed to bring the Russians to the battlefield before they, in turn, received reinforcements. But also the threat existed of intervention on his flanks from the Austrian army under Archduke Charles in Italy and that of Archduke John in Tirol, as well as the greatly enhanced possibility of Prussian involvement, since Bernadotte’s march through Ansbach. Perhaps a more cautious commander would have hesitated from advancing against an enemy force of uncertain strength to his front, while the menace of vast forces massing against his flanks and rear threatened. But Napoleon was prepared to gamble on the reluctance of the Prussians to commit to war, while he dealt with the Russian threat that was both real and immediate.

With the ceremonies at Ulm concluded, Napoleon issued orders from his headquarters at Elchingen Abbey for the army to congregate on the line of the Iser by 25 October. As stipulated in Mack’s capitulation, Maréchal Ney’s corps was unable to take part in this realignment and remained at Ulm, relegated to the tedium of guarding the prisoners. On 22 October, Napoleon made his way to Augsburg, having selected this town as the major depot for the army. But before he departed an extraordinary opportunity arose to discover the strength and dispositions of the Allied forces opposing him on the Inn.

On 21 October GD Savary received a letter from Schulmeister. Keen to contribute more to the campaign, Schulmeister offered to infiltrate Russian army headquarters at Braunau, before heading for Vienna, in order to report back on affairs in the Austrian capital, where he claimed a police inspector and a secretary to the War Council amongst his contacts.

2

Napoleon, recognising the value of Schulmeister’s offer, ordered Savary to make the necessary arrangements. Having received a large sum of money to aid his information gathering, Schulmeister left Augsburg at 1.00pm on 23 October on this new and challenging mission, still clutching the invaluable pass issued to him by Mack some days earlier.

The following day, at 6.00pm, Schulmeister arrived before the Austrian outposts at Mühldorf. He needed all his cunning and guile to pass, but on arriving in the town he searched out an old contact, Leutnant Rulzki, a hussar officer serving as an aide-de-camp to FML Kienmayer. With his generous expense budget, Schulmeister entertained Rulzki extravagantly that evening, and having stated that he had come from Ulm with important information, Rulzki freely advised Schulmeister on the state of Kienmayer’s corps, as well as that of Kutuzov’s Russians.

Early on the morning of 25 October, Rulzki escorted Schulmeister to Braunau, where he took him to Merveldt. Taken in by Schulmeister’s convincing act, Merveldt considered him to be ‘an advisor of complete confidence’ and listened attentively to the limited information he offered on French movements. He told of Napoleon entering Munich the previous day, and that the divisions of Suchet, Dumonceau and Soult, as well as the Garde Impériale, were about to join him there that day. The information was true, but hardly crucial to the outcome of the campaign. Merveldt forwarded the details to Vienna. In the meantime, the Austrian commander, totally convinced of Schulmeister’s veracity, rewarded him with 100 ducats and issued him a new pass, expecting him to return shortly with more information. He never saw him again.

Meanwhile, Schulmeister, donning the uniform of an Austrian officer, mingled amongst the Russian staff officers and learned that Kutuzov would fall back from Braunau and not fight until he received reinforcements. By 3.00pm on 25 October, Schulmeister began his return journey through the Russian and Austrian lines, armed with his new pass. He observed the outlying Russian soldiers pulling back towards Braunau and saw Kienmayer’s entire command retiring on the town from their advanced positions at Mühldorf. With the bridge over the Inn at Mühldorf now destroyed, he took a detour back through Landshut, where he stayed that evening before arriving in Munich on 26 October. There, after his round trip of

approximately 230 miles, Schulmeister immediately presented a written report to Savary. Besides the movements and strength of the Allied formations, he added much detail describing the appearance and bearing of the troops he encountered, as well as impressions of their uniforms, arms and equipment, the condition of their horses, and their knowledge of the current situation on other fronts. All in all, it was a most complete report.

3

While Schulmeister gathered his information, Napoleon finally entered Munich on 24 October, as his army assembled along the Iser, preparing for the next phase of the campaign. The city welcomed Napoleon as the liberator of Bavaria and his appearance ushered in celebrations that continued for three days. Then, on 26 October, he launched La Grande Armée over the Iser in three great columns, determined to catch and defeat Kutuzov’s army before it received reinforcements.

The news of the capitulation of Ulm changed the nature of the campaign in Italy too. Archduke Charles had already expressed his doubts as to Mack’s strategy – doubts he voiced loudly to the kaiser – and as a result, received approval from Vienna on 5 October to delay his own offensive in northern Italy until the outcome in Bavaria became clear. Shortly after his arrival at the front, Charles concluded an armistice with the French commander, the bold and tenacious Maréchal Masséna, while both sides awaited news. The armistice stipulated that six days’ notice be given by either side before a resumption of hostilities. On 11 October, Masséna gave that notice, having received notification of the arrival of the main French army on the Rhine. In the early hours of 17 October he launched an attack across the Adige river that separated the two armies. His attack met with success, allowing him to establish a bridgehead across the river, but he then waited for further news from Bavaria before making his next move. Charles used this lull to gradually withdraw his men to a strong fortified position at Caldiero, a few miles east of the Adige.

On 24 October, news of Mack’s surrender reached Charles and he informed Vienna that it was his intention to fight a battle at Caldiero. He hoped that by inflicting significant casualties on Masséna, it would deter the French commander from a rapid pursuit, enabling him to fall back to the Danube valley to aid in the defence of Vienna. Masséna only received the news of Ulm on the evening of 28 October and the following morning he launched his attack against Charles’s army. Three days of ferocious fighting followed, as Masséna attempted unsuccessfully to break through the Austrian position, and on 31 October, with casualties mounting, he broke off and pulled back.

Charles considered this the appropriate moment to commence his retreat, and so in the early hours of 1 November, he abandoned the Caldiero position, leaving only a small rearguard to disguise his move. It did not take Masséna

long to discover the ruse and by 2 November his leading troops were harassing Charles’s rearguard as they, too, fell back.

For the next few days Charles and Masséna both handled their respective commands with great skill, but having crossed the Piave river on 5 November, Charles finally broke free. The French commander continued to pursue Charles at a distance until reaching the Isonzo river on 16 November. Having been without any news from the main army for many days, Masséna decided to halt until he was able to establish communications once more. Mindful of the need to concentrate his forces, Archduke Charles issued an order for his brother, Archduke John, to abandon Tirol and to join him in the defence of Vienna. It took over three weeks before the imperial brothers were reunited, and by then the campaign had taken another dramatic turn.

Away to the north, Archduke Ferdinand, having broken out of Ulm, reached safety on the Bohemian border at Eger on 21 October. He continued eastwards towards Pilsen and began to draw together detachments into a new reserve formation. With this concentration underway, he departed for Vienna to inform the kaiser personally of the disaster at Ulm. He arrived in the city on 28 October, a day after Mack, who was forbidden to enter Vienna. Mack remained at a village on the outskirts, where he gave his full account of the entire campaign to officers sent by the kaiser. From there he was escorted to ‘some place, which he was at liberty to choose of in the vicinity of Brünn, there to await the [kaiser’s] further orders’.

4

Well received by the kaiser, Ferdinand lost no time in heaping all the blame for the loss of the army at Ulm on Mack’s shoulders. Sir Arthur Paget reported that he accused Mack of ‘ignorance, of madness, of cowardice, and of treachery’, claiming amongst other things that Mack gave information to the enemy of the route he had taken in his retreat.

5

Paget concluded that: ‘It is in short impossible that a greater degree of rancour and animosity can exist than that between General Mack and his antagonists.’ Reviewing Mack’s defence, Paget summarised that the Austrian commander firmly laid the blame at the feet of Ferdinand ‘and the rest of the general officers, to whose ill will and opposition he openly attributes his calamities which have happened … he contends that his determination was never to surrender, and that he was driven to that extreme by the protestations of the army against any further resistance.’

The kaiser, perhaps overwhelmed by the vehemence of the accusations, reproached Ferdinand for not having placed Mack under arrest, causing the archduke to remind him ‘of the full powers he had invested in the general, and the [kaiser] acknowledged the fault he had committed’. But a scapegoat was required and it would not be coming from the imperial family. Mack was committed to appear before a court martial. Ferdinand remained in Vienna for just two days before returning to Bohemia to complete the formation of his new reserve corps.

6

As the Archdukes Charles, John and Ferdinand, fell back to positions from where they hoped to play an important part in the second phase of the campaign. Kutuzov, at Braunau, still waited with growing concern for news of Russian support. When he left Russian territory on 25 August the other two main columns were advancing towards the Russian–Prussian border with the intention of intimidating the Prussians to allow their passage through Prussia. Britain and Austria agreed that if Prussia opposed such a move then Russia should enter aggressively. When Tsar Alexander joined his men on the Prussian border on 27 September the Russian columns still waited on a final decision, as King Frederick William vehemently maintained his neutrality in the face of Russian threats.

In fact, the Prussian monarch was becoming concerned – with justification – by Russia’s glances toward the former Polish lands now encompassed as Southern Prussia. He knew that the tsar’s deputy minister for foreign affairs, the Polish prince, Adam Czartoryski, held much influence over Alexander, and indeed, Czartoryski had encouraged Alexander to believe that if he marched on Warsaw, the Polish nobles would rise under the Russian banner against Prussia. At one point, the tsar confirmed to Czartoryski that he intended following this plan, but later wavered and finally abandoned it, much to the disappointment of the deputy minister.