Avoiding Prison & Other Noble Vacation Goals (22 page)

Two days later, a group of prisoners had crept up on Francisco while he was sleeping, surrounded his bed with newspaper, and lit it on fire. Luckily, only Francisco's legs had gone up in flames and he was spared his life, but I couldn't look at the blisters on his skin without wondering how much more time he'd be able to hold out there.

If there was ever a time for me to flee responsibility, this had to be it. Other men had required less of me and I still had fled the burden of their problems. Yet the very gravity of the situation was what compelled me to stay. My boyfriends in the past may have lost a few nights sleep over me; I knew that Francisco would be in serious jeopardy of losing his life.

Although Francisco was mild mannered and gentle and had little chance of holding his own in a fight, he had an advantage over the other inmates: my money. Twenty, thirty, forty dollars a week was a small price to keep Francisco alive, and with it he was able to make friends, offering cigarettes, food, and a bill now and then to the other prisoners who knew better than to bite off the hand that fed them.

This was what it had taken for me to commit to the long haul with a manâthe threat of my boyfriend's impending death if I didn't. It was the universe's big joke on me: “You can't deal with another person's neuroses, annoying personal habits, and bad morning breath? How about this: Fall in love with a man who loves freedom as much as you do and now, let's see here, we'll have him locked away in a prison.” Good God, even destiny had a sense of irony.

Reaching out and touching someone was relatively simple if you had to dial a mere seven numbers plus an area code, but making contact with my family was getting increasingly complicated. It wasn't just the elaborate international prefixes, the problem of being heard over crackling Third World phone lines, the prohibitive cost of a ten-minute call; the reason I didn't pick up the phone to have a detailed heart-to-heart about what was currently happening to me (i.e., the whole boyfriend/prison/breakout inconvenience) was because of the fact that it was completely impossible to have a serious conversation with my parents. Sure, they were a blast to hang out with when everything was fine, but when it came down to the worst tragedies of my life, my parents had always proven themselves useless in a crisis.

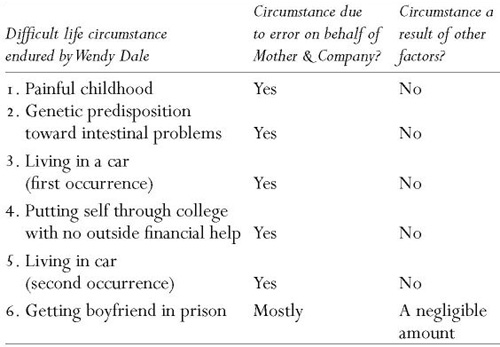

Recently I had traced the path from birth to this point in my life and all the places where things had gone wrong, guess who was to blame. That's right: Mother & Company, headed by none other than Cathie Dale herself. (My father was like a low-ranking receptionist at Make Wendy's Life Miserable, Inc., sharing a small portion of my resentment but only loosely affiliated with this baneful institution.)

I submit the following examples as proof:

Conclusions

Wendy Dale's unhappiness quotient is due in large part to the actions

taken on behalf of Mother & Company, with blame laid at 98.4 percent and

1.6 percent for Mother & Company and other factors, respectively.

If you will bear with me for a minute, let's examine the chart in detail. Items 1 and 2 are relatively apparent: Cathie Dale was obviously a witness and at times a participant in issues ranging from childhood through doctor visits. Item 3 has been discussed previously in this book (see page 25); however, Items 4 and 5 may require some additional explanatory materials (see Addenda 1 and 2 below):

Addendum 1

PUTTING SELF THROUGH COLLEGE

WITH NO OUTSIDE HELP

A scene by Wendy Dale

(Based on a true story)

Wendy, age nineteen, a student working for five dollars an hour struggling to

put herself through college recently wound up in the emergency room, where

she was diagnosed with a stomach ulcer. She is currently at her sparsely furnished apartment in Los Angeles going through her mail. She opens up a letter and stares at it.

WENDY:

(takes a deep sigh)

Woe is me. Oh dear! Whatever shall I do? Five hundred dollars for my recent stay in the hospital where I was diagnosed with a very painful stomach ulcer as a result of the extreme stress I am under working three jobs where they pay me five dollars an hour while I try to put myself through school. Oh well, I guess I'll just have to pay for it with my tuition money that I worked so hard to save.

Two weeks later Wendy is making a phone call from her sparsely furnished

bedroom in Los Angeles. (She does not have a cordless phone. She could not

a ford one.)

WENDY:

(takes a deep sigh)

Mom, would you please loan me five hundred dollars for my tuition at UCLA?

CATHIE:

(in a very mean voice with no compassion whatsoever)

Wendy, you know how expensive our trip to Morocco, England, and Spain was. Plus we just bought a new car.

Addendum 2

LIVING OUT OF A CAR

(A sequel to “Putting Self Through College

with No Outside Help”)

Another scene by Wendy Dale

(Based on a true story)

Wendy, age twenty, a college student who has paid her own tuition for two

years now has wound up with no place to live due to a psycho roommate who

changed the locks on their shared apartment. (Note: This psycho roommate

also took most of Wendy's things.)

Wendy is at a pay phone with her car full of clothes in a very bad

neighborhood that any normal mom would not want her daughter to

be in.

WENDY: Hi, Mom, it's Wendy.

Wendy's mom is in a very nice house eating very expensive chocolate imported

from Germany. It's obvious thatWendy's mom does not have any serious prob

lems whatsoever.

WENDY: Mom, my roommate just kicked me out. I'm homeless. I don't have anywhere to live.

CATHIE:

(takes a bite of chocolate)

That's must be very hard for you, Wendy.

An hour later,Wendy snuggles up in her car, rubbing her hands together trying to get warm.

WENDY: It sure is hard being homeless. I guess it's going to be a long night.

Granted, this was a somewhat one-sided version of events as they occurred but it was the way the scenes played out in my head. And it was relatively close to the truth: My mother did refuse to loan me tuition money after I'd wound up in the hospital. She claimed that they just couldn't afford it right now since they'd just returned from Europe and purchased a new car. And I really did live out of my car for two months, to which my mother's only response was that my situation was undoubtedly very difficult.

These were the reasons I never told her any of the significant details of my life. These were the things I held against herâagainst

her,

not my dad.

Granted, my father had played his part in my life problems, but my mother was the one I blamed, mostly because my contact with him had always been so limited. He was continually working long hours to support the family, in part because my mother rejected the notion that she should get a job. He was never home when I called so any information to be imparted to him had to go through her first. I never got to plead my case with him directly, so I absolved him of any blame. Besides, we all knew that my father didn't care for material comforts. How could we accuse him of depriving us of something that he didn't value himself?

Now that I was alone in a foreign country facing what was undoubtedly the most difficult obstacle of my life, I had a very good reason not to call. I desperately needed someone to be there for me, but I already knew what my mother's response would be: “Oh, that must be very difficult for you.”

I had survived tough circumstances before. Even homeless, I hadn't gone running to my parents'. I would do it again. Costa Rica wasn't going to get the best of me without a fight.

The embassy offered no help, Francisco's lawyer was discouraging, and my own formal legal training was nil, but I figured that I had years of experience in its twin discipline: ad copywriting. I reasoned that if I could sell shampoo to bald men and fireplaces to residents of Malibu, it shouldn't be that much of a stretch to sell justice to Costa Rican officials.

“The first step,” I said to Francisco excitedly at our next visit, suddenly knowing what I had to do, “is get you out on bail. They've already denied you this five times because they say you're a foreigner with no ties to Costa Rica and that you'll flee if they release you.”

“So what do we do?”

“What we do,” I said, uttering the triumphal phrase that had gained me prestige and hefty paychecks in corporate offices across Los Angeles, “is construct a public-friendly image of you.”

Francisco let out an appreciative “ohhhhh.”

“The way I see it, they view you as this foreigner who came to Costa Rica with every intention of stealing your ex-wife's car. We're going to create a different image. You are a father, a responsible citizen, a man with a Costa Rican daughter who considers this country his home. What is missing from your files is the other side of the story: that you lived and worked here for four years, that you have a daughter here, that you have good credit, anything that will show you're a respectable human being.”

“Respectable human being?” Francisco let out a dejected “ohhhh.”

“Yes, I realize. I have my work cut out for me.”

Knowing that Francisco had worked at a travel agency for three years in Costa Rica, I figured I could get a good reference from his employer.

“Where do you think your old boss is now?”

“That seems to be the million-dollar question, doesn't it?”

I wasn't the only one looking for this man; half of Costa Rica was after him. The travel agency where Francisco worked had turned out to be a front for laundering Yugoslavian money, which meant that even if I could get in touch with him, his reference probably wasn't going to do Francisco a lot of good.

“But the travel agency manager will help me out,” Francisco said.

“Great. Where do I find him?”

“Well . . .”

Francisco wasn't exactly sure where his old manager was (it had been more than three years since Francisco had left Costa Rica the last time), but he had a friend named Rafael Quiroga who worked at another travel agency and could help me get in touch with him.

The next day in search of Mr. Quiroga, I entered the largest, most bustling travel agency I had ever seen. After stumbling into three offices and failing to find reception, I finally found the right room and asked a busy secretary wearing a headset where I could find Rafael Quiroga.

“Rafael Quiroga? Rafael Quiroga? Carlos, is there anybody here named Rafael Quiroga?”

“I don't know any Rafael,” the man said, gliding past the receptionist.

A woman carrying a stack of files rushed by. “Do you know anyone here named Rafael?” the receptionist asked her.

“Ask Jaime,” the woman responded, sliding out of the room.

The receptionist made a phone call. “Jaime . . . yes . . . yes . . . anyone here by the name of Rafael Quiroga? Great, thanks.”

“There's a Rafael Quiroga in Accounting,” the receptionist informed me. “Down the hall, third office on the left.”

Sure enough, there was a Rafael Quiroga in Accounting. He just wasn't the Rafael Quiroga I was looking for.

“You must mean the Rafael Quiroga who works for us on a contract basis,” the wrong Rafael Quiroga informed me.

“Where do I find

him?”

I asked.

“Talk to Rolando in Administration, down the hall, exit the building, go around the corner, and it's the first door on the right.”

“Rafael Quiroga, of course I know Rafael Quiroga,” Rolando in Administration said, reclining in his chair. “I have his number here in my Rolodex. Let's give him a call.”

He dialed seven numbers and waited.

“Rafael Quiroga, pleaseâwhat? What number have I called? And there's no Rafael Quiroga there? Sure? Well, thanks.”

“Wrong number,” he said to me with a shrug, replacing the useless card back into his Rolodex. “But he has to come in here tomorrow. Would you like to leave him a note?”

“Sure,” I said, frustrated. “Could you loan me a pen?”

“Hey, anyone around here have a pen?” Rolando shouted out.

I left a note and returned the next day.

“Any sign of Rafael Quiroga?” I asked Rolando.

“Yeah, he came by and it turns out he's not the Rafael Quiroga you're looking for. But he's a private investigator and he said he'd help you find the guy if you'd like.”

“Do you have his phone number?”

“Sure, it's right here in my Rolodex.”

I had once discovered that the only cure for depression was to do the thing I least wanted to. What I least wanted was to get out of bed, to face my circumstances, but in doing it every morning, in forcing myself out of the house, my depression subsided into a constant nervous anxiety. And focusing on Francisco's case kept my mind occupied, preventing my thoughts from convincing me how impossible the whole situation was. Because if I were to face the facts, there really were no grounds for hope. The Costa Rican legal system was based on the Napoleonic Code, which meant that a man was guilty until proven innocent. But try proving that someone

didn't

do something. And add to it the fact that his only alibis were criminals.