B0041VYHGW EBOK (107 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

6.118 Shot 9: A cut back to the two-shot supplies Smith’s satisfied reaction.

6.119 Exley turns away. The lens shifts focus to catch his grim face in the foreground, preparing us for the brutality he will display.

6.120 Exley walks out of the shot. The camera tilts down slightly and racks focus to display Vincennes’s skeptical expression. The telephoto lens, accentuated by the rack-focus, has supplied facial views of Smith, then Exley, and then Vincennes in a single shot.

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

After you’ve read about

L.A. Confidential,

check out our blog entries on the Bourne trilogy, in “Unsteadicam chronicles”

www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=1175

, “[insert your favorite Bourne pun here]”

www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=1230

, and “I broke everything new again”

www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=1285

.

We also compare a scene in

The Shop Around the Corner

with the same one in the remake,

You’ve Got Mail,

in “Intensified continuity revisited,”

www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=859

.

For thoughts on multiple-camera shooting and continuity, see “Cutting remarks: On

The Good German,

classical style, and the police tactical unit”

www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=91

.

Why did this intensified form of continuity become so common? Some historians trace it to the influence of television. Recent movies were broadcast by TV networks in the 1960s, transmitted by cable and satellite in the 1970s, and available on home video in the 1980s and 1990s. As people saw movies on home screens rather than in theaters, filmmakers reshaped their techniques. Constantly changing the image by cutting and camera movement could keep the viewer from switching channels or picking up a magazine. On smaller screens, faster cutting is easier to follow, and closer views look better than long shots, which tend to lose detail. Intensified continuity was shaped by many factors, such as the arrival of computer-based editing, but television was a major influence.

Sometimes, however, a second possibility will be explored:

temporal ellipsis.

The ellipsis may omit seconds, minutes, hours, days, years, or centuries. Some ellipses are of no importance to the narrative development and so are concealed. A classical narrative film doesn’t show the entire time it takes a character to dress, wash, and breakfast in the morning. Shots of the character going into the shower, putting on shoes, or frying an egg might be combined so as to eliminate the unwanted bits of story time. As we saw on

pp. 233

–234, optical punctuations, empty frames, and cutaways are frequently used to cover short temporal ellipses.

But other ellipses are important to the narrative. The viewer must recognize that time has passed. For this task, the continuity style has built up a varied repertoire of devices. In films made before the 1960s, dissolves, fades, or wipes are typically used to indicate an ellipsis between shots, usually the end of one scene and the beginning of the next. The Hollywood rule is that a dissolve indicates a brief time lapse and a fade indicates a much longer one.

Contemporary filmmakers usually employ a cut for such transitions. For example, in

2001,

Stanley Kubrick cuts directly from a bone spinning in the air to a space station orbiting the earth, one of the boldest graphic matches in narrative cinema. The cut eliminates millions of years of story time. Less drastically, most contemporary films indicate the passage of time through direct cuts. Changes in lighting, locale, or character position cue us that story time has passed

(

6.121

–

6.123

).

6.121

Wendy and Lucy:

Arrested for shoplifting, Wendy is being fingerprinted, and she glances up at the clock. She’s worried about having left her dog Lucy at the supermarket.

6.122 The clock shot has functioned as a cutaway to cover a time gap. This shot of Wendy in a cell indicates that some minutes have elapsed since she was fingerprinted.

6.123 Wendy’s marked change of position from the previous shot suggests that still more time has passed. An older film would have implied the passage of time through dissolves, but here the abrupt changes of locale and character position suggest the same thing. A later shot of the clock will show that Wendy has been held for at least two hours.

In other cases, it’s necessary to show a large-scale process or a lengthy period—a city waking up in the morning, a war, a child growing up, the rise of a singing star. Here classical continuity uses another device for temporal ellipsis: the

montage sequence

. (This should not be confused with the concept of

montage

in Sergei Eisenstein’s film theory.) Brief portions of a process, informative titles (for example, “1865” or “San Francisco”), stereotyped images (such as the Eiffel Tower), newsreel footage, newspaper headlines, and the like can be joined by dissolves and music to create a quick, regular rhythm and to compress a lengthy series of actions into a few moments.

American studio films of the 1930s established some montage clichés—calendar pages fluttering away, newspaper presses pounding out an Extra—but in the hands of deft editors, such sequences became small virtuoso pieces. The driving pace of gangster films like

Scarface

and

The Roaring Twenties

owes a lot to dynamic montage sequences. Slavko Vorkapich, an experimental filmmaker, created somewhat abstract, almost delirious summaries of wide-ranging actions such as stock market crashes, political campaigns, and an opera singer’s career

(

6.124

).

6.124 In

May Time,

Slavko Vorkapich uses superimpositions (here, the singer, sheet music, and a curtain rising) and rapid editing to summarize an opera singer’s triumphs.

Citizen Kane

ironically refers to this passage in the montage sequences showing Susan Alexander’s failures.

Montage sequences have been a mainstay of narrative filmmaking ever since.

Jaws

employs montage to summarize the start of tourist season through brief shots of vacationers arriving at the beach. A montage sequence in

Spider-Man

shows Peter Parker sketching his superhero costume, inspired by visions of the girl he loves

(

6.125

,

6.126

).

All these instances also remind us that because montage sequences usually lack dialogue, they tend to come wrapped in music. In

Tootsie,

a song accompanies a series of magazine covers showing the hero’s rise to success as a soap opera star.

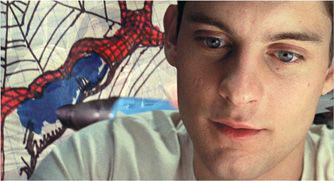

6.125 For a montage sequence in

Spider-Man,

CGI technique creates a split image, showing both Peter’s expression and a close-up of the costume he’s designing.