B004R9Q09U EBOK (13 page)

Authors: Alex Wright

In the century before the fall of Rome, the unwieldy 12-foot-long papyrus scrolls of Alexandria had started to cede room on the shelves to a new form of document: the codex book, so named because it originated from attempts to “codify” the Roman law in a format that supported easier information retrieval. The new format boasted a more navigable interface, featuring leafed pages bound between durable hard covers. Not only was the new format more resilient than the carefully wound scrolls that preceded it, it facilitated a new way of engaging with the text. Scrolls, by their physical nature, demanded linear reading from start to finish. They required a commitment on the part of the reader and resisted attempts to extract individual nuggets of information. But with a codex book, readers could now flip between pages easily to pinpoint any passage in a text. As Hobart and Schiffman write, “The codex had the potential to transform the manuscript from a cumbersome mnemonic aid to a readily accessible information storehouse.”

2

The new technology of the book ushered in a whole new way of reading: random access. A document no longer had to be read from top to bottom; its pages could be flipped, allowing the reader to move around at will. By letting users move freely from page to page, the new book allowed readers to form their own networks of association within a particular text. Scrolls, on the other hand, encouraged linear reading. The book also had one more considerable advantage over the old scrolls: portability. While collections of papyrus scrolls and codex books coexisted in late Roman libraries, the destruction of the empire saw most of the great old library collections burned, plundered, or scattered. The codex book format proved hardier and more portable than the old scrolls; as a result, many scrolls failed to survive the fall of the Roman empire, and a great deal of the literature that lived on did so between the covers of bound books.

By the fifth century AD, Rome had conquered much of continental Europe and most of the neighboring island of Britannia, dispersing copies of books that would eventually make their way into monastic libraries throughout the former provinces. For all of Rome’s far-flung conquests, one island had always lain just beyond its reach: Ireland (or, as it was called, Hibernia). Throughout the era of Roman conquest, the Irish had lived in tribal communities not far removed from the preliterate cultures of Mesopotamia, Australia, or North America. Knowing nothing of reading, let alone Aristotle, people lived in small social groups with warring feudal kings and a shamanistic religious tradition, Druidism. Lacking any form of written language, they relied on oral traditions, mythology, and a web of symbols to preserve their understanding of the world. The old Druidic system was conceptually not far removed from the multilayered ancient folk systems of China, Greece, or aboriginal Australia.

The Irish Celts were a famously bellicose people, who warred with each other and occasionally raided neighboring England, where in the early fifth century a group of Irish pirates brought back a recalcitrant young slave named Saccath. After working naked in the fields tending goats for several years, the slave managed to escape his captors and find his way to Gaul, where he spent the next 12 years at the monastery of Saint Germain, learning to read and studying the Gospels. Eventually, he decided to leave the monastery, vowing to return to Ireland to spread the word of God among his former captors. In the course of fulfilling that aspiration, the onetime slave—known to us now as Saint Patrick—would forever alter the course of Western European thought.

While Saint Patrick was not the first Christian missionary to reach Ireland, he was certainly the most successful. Within a mere 30 years he managed to convert the entire Irish population to the new faith. While Patrick’s success undoubtedly had a great deal to do with his personal charisma, he also had technology on his side. Patrick introduced the Irish to the written word. He returned to Hibernia armed with a copy of the Latin Gospel. That lone volume would become the catalyst for Ireland’s encounter with literacy. Patrick initiated the long process of transplanting the literate culture of classical

antiquity into the shamanistic oral culture of Ireland. The result was an extraordinarily successful cultural adaptation. The drift of classical literacy to the remote island culture resulted in a beautiful new art form with lasting cultural consequences: the illuminated manuscript.

While the Irish were hardly the first tribal culture to come in contact with the literary arts, their experience differed in one important respect from previous historical encounters with literacy. Before the emergence of the bound book, literate cultures had always introduced the technology of writing to nonliterate people in a linear format: in stone, clay tablets, or papyrus scrolls. The Irish were the first people to learn to read from books. Ever since, Irish literacy has been inextricably bound (so to speak) with the form of the book.

The sudden introduction of this new, random-access form of writing to a previously illiterate tribal society sparked a collision of cultures that would yield dazzling literary byproducts. In short order the Irish managed to embrace both writing and books, while imbuing them with their own unique cultural sensibilities. In the coming centuries, Ireland would become a kind of literary research and development laboratory, populated by talented scribes with a knack for innovation, working together in an environment largely insulated from the continental ravages of the Dark Ages. For the next 500 years the Irish scribes not only preserved the classical texts of the old Roman world, they also recorded their own indigenous Celtic mythologies and folklore, infusing bound books with their cultural heritage of storytelling and symbolism. Unencumbered by the institutionalized hierarchies of Rome and knowing nothing of government bureaucracies, religious institutions, or schools, the tribal people of Ireland took to literacy with zeal. Newly literate Irish monks began to navigate the great corpus of classical and scriptural knowledge. At first the early Irish manuscripts were artistically primitive affairs, scratched out on poor-quality vellum (made from cows’ stomachs) and stuffed with cramped and inconsistent handwriting. But the scribes learned quickly and soon showed a remarkable aptitude for the literary arts, mastering the finer points of majuscule and minuscule scripts, making notes in the marginalia, and decorating their texts with clever, sometimes provocative, illustrations. Within a century

they were producing manuscripts of astonishing beauty. These new kinds of books would become the gold standard of European illuminated manuscripts. Within two centuries, Irish scribes were producing breathtaking specimens like the

Book of Kells

and later the

Lindisfarne Gospel

. The illuminated manuscript became Dark Age Ireland’s national art form.

For the scribes, copying manuscripts was an act of private devotion and contemplation rather than a rote task. While the popular historical stereotype paints the monastic scribe as a dour clerical type, making laborious transcriptions—like the famous Xerox TV commercial caricature—the early Irish scribes were in truth anything but human copy machines:

[The scribes] did not see themselves as drones. Rather, they engaged the text they were working on, tried to comprehend it after their fashion, and, if possible, add to it, even improve on it. In this dazzling new culture, a book was not an isolated document on a dusty shelf; book truly spoke to book, and writer to scribe, and scribe to reader, from one generation to the next. These books were, as we would say in today’s jargon, open, interfacing, and intertextual—glorious literary smorgasbords in which the scribe often tried to include a bit of everything, from every era, language, and style known to him.

3

The scribes found ample opportunities for exploration in making sense of these imported coded texts. Their capacity for inventiveness and experimentation stemmed in no small part from their near-total isolation from the Roman Church, which elsewhere on the continent was beginning to establish a governing structure with restrictive rules for its burgeoning monastic orders and churchmen. But in Dark Ages Ireland the scribes enjoyed a great deal of artistic leeway.

The Irish scribes not only preserved countless important texts but in the centuries that followed also propagated those texts back to a continental Europe that had descended into near-barbarism. Most of the great Roman libraries failed to withstand the ravages of the Dark Ages. And while a few monasteries managed to preserve important collections of church texts and works by classical authors, no one

else came close to approaching the artistic innovations of the Irish scribes. Without the Irish contribution, Europe might well have lacked the intellectual fortitude to withstand the expansion of Islam in the early Middle Ages. Eventually, the Irish style would work its way back to the continent, and conversely, continental scribes would influence the Irish to adopt a more conventional style. Irish monks began to adopt the uncial script style of the continent, while the Irish techniques of lavish illustration and marginalia seeped into the continental manuscripts. The cultural mutations of the Irish manuscripts became part of Europe’s cultural DNA.

The early Celtic Church that began in Ireland soon spread across the Irish Sea to Scotland and then to England (and eventually, as far as Iceland and Italy). In contrast to the great institutional hierarchy of the Roman Church that would eventually displace it, the early Celtic Church was mostly a grassroots operation, self-organized, gender-harmonious (monks could marry), and geared primarily around individual contemplation rather than institutional dogmatism. While the Roman Church would eventually flex its political, economic, and military muscle to bring the wayward Irish scribes (and their British colleagues) back into the administrative fold, during the critical period following the collapse of Rome, Ireland harbored a period of remarkable literary innovation that would have lasting consequences for European culture. The legacy of the early Celtic Church—with its antihierarchical, individualist emphasis—would reverberate for centuries.

In the archetype of the Irish scribe—the original literary intertwingler—can we recognize a distant ancestor of today’s blogger? Working outside of any traditional institutional hierarchy, engaging whatever topics interest him, interpolating words and images using a newly introduced communications technology, the scribe and the blogger seem like kindred literary souls. While we should be careful of stretching the parallel too far, the introduction of new technology in both cases seems to have given rise to a new ethos of self-directed writing, holding the promise of entirely new forms of expression.

The medieval manuscript not only opened up the possibility of random access to the contents of a document but also gave rise to

new forms like marginalia, inline illustrations, and layered type styles that allowed readers to engage medieval manuscripts in a manner not far removed from what we now think of as hypertext. The scribes recognized the importance of visual cues, fusing words and images to create juxtapositions of meaning beyond the mere concatenation of words on a page. The Irish style of manuscript, with its lower minuscule-style typeface (as opposed to the uncial style prevalent on the European continent), became the artistic signature of the early Celtic Church. Irish scribes brought the style to England, where it flourished in the great monastery at Lindisfarne and became the foundation for the early English scriptoria that produced such works as the

Lindisfarne Gospel

.

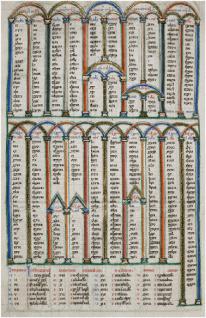

One signature of the

Lindisfarne Gospel

is its Canon Tables, symbolic arches containing cross-references between sections of the Gospel. Designed to resemble a church, the Canon Tables were both metaphorical (a symbol of God’s word housed in the church) and practical reference tools enabling the reader to move between related sections in the text, a kind of illuminated hypertext.

While historians of the book celebrate the artistic achievements of great manuscripts like the

Lindisfarne Gospel

and the

Book of Kells

, the vast majority of books produced in the early scriptoria were simpler affairs, intended for practical purposes. Scriptoria often produced durable copies of the Gospels to equip Christian missionaries on their journeys across the continent, where they used the texts to convert the pagans they encountered by wielding the power of God’s “spell” (“Gospel”). The popular image of illuminated manuscripts suggests that they were the property of cloistered monks counting their proverbial angels on the heads of pins, but many early manuscripts went out into the world. Their physical heft and rich symbolism proved to be powerful physical totems against the disembodied oral traditions that held sway over the illiterate souls the missionaries intended to save. Often, when missionaries first encountered a pagan tribe, they would approach their prospective converts bearing a cross in one hand and a book in the other. To the illiterate tribes the book carried far more power as a symbolic object than as a container of words, representing what Christopher de Hamel calls “tangible proof of their message”

4

and a potent counterargument to ethereal oral traditions.

For the next thousand years, the monastic art of book making would play a central role in the spread of Christianity.

Canon Table, from a Bible made for the monks of Saint Albans Abbey in 1170. Cambridge: Corpus Christi College, MS. 48, fol. 201v. Reproduced by permission of The Master and Fellows of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, England.