B004YENES8 EBOK (3 page)

Authors: Barney Rosenzweig

As originated by Barry Diller and his ABC minions—and subsequently by Fred Silverman and his subordinates first at CBS, then ABC, and NBC —this system could be very oppressive and wasteful. In the more than thirty years that have followed—with all their power and virtually unlimited funds—the networks have managed to create less than a half dozen superstar hyphenates. Enormous amounts of capital expended, a lot of talented, passionate, hardworking producers buried, to create—over an entire generation—a handful.

You cannot cut down rain forests in Brazil and not have it affect the weather in North America. You cannot build concrete canyons in areas that were once flat and not get wind. Swimming pools and golf courses in desert resorts have raised the humidity and caused rainy seasons and droughts, where heretofore they did not exist.

In the 1970s, Diller, Silverman, and a young group of network executives messed with the ecology of Hollywood. Their imprimatur is still being felt. Of more importance to this piece is that this is where I found myself all those years ago: an overqualified, true, non-writing producer in an awful rising tide, just trying to survive the onrushing tsunami.

Chapter 3

LIMBO WITH GRANDMA FANNY

Back at Filmways, Ed Feldman was not having any success in getting financing for a

Cagney & Lacey

motion picture. Every studio head then in Hollywood was male. Confronted with the

Cagney & Lacey

screenplay, they demurred. They simply didn’t believe the script. They did not accept that women talked to each other or related to each other in the way we had indicated.

The men of Hollywood had their own mythology, reinforced by the films of their predecessors (also males):

“A woman isn’t a woman until she’s had a child.”

“A woman might have a job but would give it all up in a minute for the ‘right’ man.”

“Women can’t, and don’t, have friendships the way men do.”

“Women are in constant competition for Mr. Right.”

… And, the seemingly inevitable male fantasy of the Madonna/Bitch.

Is it any wonder Hollywood had never produced a buddy movie for women?

Sherry Lansing , the recently retired head of Paramount Studios and the producer of

Fatal Attraction

, among other films, was, in 1975, a youthful assistant to Dan Melnick , the MGM studio chief of the moment. She liked the Avedon & Corday screenplay and kept hounding her mentor to consider it for production. Her persistence outlasted his obstinacy. He finally condescended to make an “offer.” He would fund the movie for $1.8 million contingent on getting Ann-Margret and Raquel Welch as the two women leads.

It was all pretty silly. In the mid-1970s it was barely possible to hire these two women for that price, let alone have enough left over to make a film. Furthermore, it should be remembered just who Ms. Margret and Ms. Welch were all those years ago. Neither had yet achieved the hard-won recognition they have today as talented actresses; in those days they were simply symbols of Hollywood’s male fantasy of the super-endowed sex goddess. They were then the polar opposite of what we were trying to accomplish with

Cagney & Lacey

and, so as to keep the record straight, our prototypes for casting in those early days were Sally Kellerman and Paula Prentiss.

Things were also not going so well on my other project with a female lead. The written presentation for NBC by Avedon & Corday on

This Girl for Hire

is to this day one I use as a reference and an example for would-be pilot makers to follow. It is well-written, entertaining, and informative. The reader of those less than two dozen pages knows exactly what the show is about, what the film will look like, what the characters sound like, how they dress, and how they relate to each other. It made it very easy to visualize not only the eventual screenplay but the film itself. It was such a strong guide that it all but guaranteed a solid screenplay. All one had to do was follow the map of that presentation to pay dirt.

We had been operating under the guidance of network development executives Lou Hunter and Deanne Barkley. Now the project had stalled before going to the final stage of ordering a pilot script. Irwin Segelstein , then of NBC ’s upper echelon, had pulled the plug.

“A woman’s place is in the kitchen and the bedroom,” he said to his staff. What Deanne Barkley rejoined I do not know. What I do know is we were out of business at NBC and that Ms. Barkley didn’t stay around at the network too much longer after that.

That spring, across town, the team of Aaron Spelling and Leonard Goldberg had struck some pay dirt of their own with a show featuring women. It was called

Charlie’s Angels

, and it had made the ABC lineup for the fall of 1976. The good news was I was on the Spelling/Goldberg shortlist of producer-for-hire candidates. The bad news? Another Spelling/Goldberg series,

The Rookies

, had finally been canceled. Its writer/producer had been Rick Husky, who ten years before had been my protégé on

Daniel Boone

(my first producing job) and before that (in the early 1960s) at the MGM publicity department. It was on

Daniel Boone

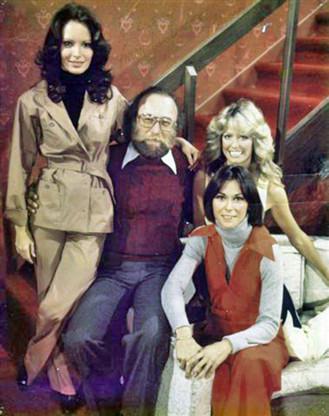

that Rick had received his first writing assignment, launching his career. Now he was being asked to set up the company’s new series with Farrah Fawcett, Kate Jackson, and Jaclyn Smith, who he was then dating.

Rick called me within a few days. “I hear I beat you out of a job. I’m sick about it,” he said.

“Don’t be silly,” I countered. “They know you a lot better than me. You’ve been with them a long time and done a hell of a job. It’s only natural they would want you.”

“Listen Barney,” Rick said, his tone almost conspiratorial. “I’m exhausted. I really wanted a major break after my series, but I couldn’t turn these guys down. All I agreed to do was get ’em started. I’m only doing the first six episodes, so stay on top of this. Push your agent to get you in here. There’ll be a job by fall.”

Rick had heard me talk about how cold it had been on the outside. How, as a non-writing producer, trying to make a living on supervisory fees of $2,500 here and $1,750 there was a bad joke. I appreciated the tip. Meanwhile, development went on. So did the calendar. It was midway through 1976. In the four years since 1972, my name had appeared on only two productions:

Men of the Dragon

in release in 1974 and

One of My Wives is Missing

in 1975. Things were bleak.

A couple of times a month, I’d drive across town to visit my grandmothers, Fanny and Minnie. They did not live together, but both resided on Los Angeles’ east side. Minnie was my paternal grandmother. Fanny was on my mother’s side. She was also one of my principal creditors.

Neither woman was rich. No one in my family was. Fanny had worked all her life, and her needs were small. During this period, she would loan me upwards of $8,000. Instead of interest, I showed up every other week at her place. I’d eat a little boiled chicken and bring her up to date with what was going on in my life. The meetings with Grandma Minnie were shorter. She didn’t cook too much, and the conversations turned more on the Mexican-American kids in the neighborhood who were making her life so unpleasant. Show business didn’t interest Minnie. Fanny longed for the day when she would see my name on her television screen again.

One night, Fanny’s impatience at my lack of screen credit had me on the very treacherous ground of trying to explain television development to a civilian. At best this is a trying and difficult conversation. With a woman in her eighties, not noted for her powers of concentration even as a youth, this was a formidable task.

“It’s like the shmatte

1

business, Grandma.”

I thought I might have a chance here by comparing my trade to the one industry Fanny really knew. For years she had labored as a seamstress in the garment district in Los Angeles.

“I go in with my ‘dresses’. Some are long, some are short. Some have patterns, some have bright colors.”

Grandma Fanny was smiling. She was enjoying this. Am I a storyteller, or am I a storyteller?

“I go into Cole of California and to Martin, and I go into Catalina Casuals, but right now, no one is buying my dresses.” There was a pause. I presumed the metaphor was sinking in.

“Maybe I could help,” she said.

I put down my chicken leg. The napkin hid my supercilious grin. “Grandma, how could you help?”

Her tone indicated that the word

schmuck

might well have preceded her imperious statement: “I know about dresses.”

“No, no, you misunderstand. It’s an analogy.” I said this last part very slowly, pedagogically. “They’re not really dresses, Grandma. They’re ideas, projects, potential television shows. And it’s not really Cole, Martin, or Catalina. It’s ABC, NBC, and CBS. See? I go in with my stuff, and nobody’s buying.”

I looked at her. Her eyes narrowed, focusing on me. I nodded slightly as if to say, “You get it?” Then limply added, “They’re not buying my dresses.”

Grandma Fanny nodded sagely. She drew in her breath through her nose, then slowly, thoughtfully, let it escape before speaking: “Maybe you should make men’s suits.”

God, I miss Grandma Fanny. I laughed more that night than I had in years. The tension of the past months, even years, came out of me as I literally rolled on the floor in glee, totally unable to control myself. Grandma Fanny was pleased I was having such a good time.

Chapter 4

CHARLIE’S ANGELS

Spelling and Goldberg were not too pleased with the early work they were seeing on

Charlie’s Angels

. Rick Husky’s protestations of being tired were finally being listened to, and word went out for his replacement. My old Universal nemesis, David Levinson, had been brought in to produce at least a couple of episodes until it could be determined by Spelling, his partner, and the ABC network how to proceed. They would have to make a decision soon. The show was due to go on the air in a matter of weeks. I began to lean heavily on new-to-me-agent Bob Broder, regarding this “gun-for-hire” gig at Spelling/Goldberg.

“What’s the big deal here, Barney?” Broder was quizzing me by phone. “We haven’t discussed your going back to series television. You never push for any other show—what’s so special about this one?”

I was not one of Broder’s more important clients, and he obviously had no clue what it was like trying to make a living on scanty script supervisory fees. It had been months since I had had a real paying job.

“Because it’s going to be a major success, and I need to be connected to a hit right now. Because if I’m right—and this show about women detectives is a hit—then it just might get

Cagney & Lacey

and

This Girl for Hire

made. And, finally, I said, “I taught Rick Husky everything he knows. He’s a great act for me to follow!”

Broder got the picture. Within a few days I got a call from him with instructions to attend a 10 am screening at projection room F at the 20th Century Fox facility leased by Spelling/Goldberg. I was to view nearly three hours of film, then proceed to Aaron Spelling’s office for a meeting. What I was there to see was three and a half episodes of

Charlie’s Angels

, Spelling/Goldberg’s about-to-debut television series. It was pretty dreadful.

The format, as I recall, was to open with a scene of action, then cut to Charlie’s office. There, in that posh interior, a slide projector was put into operation, and,

Mission Impossible

-like, the audience (and the Angels) would be brought up to speed on the necessary expository beats of that week’s episode. Charlie’s disembodied voice would come over the telephone speaker box, adding commentary to those projected images, explaining what the caper was and what each of the Angels was to do. Then, in varying degrees of harmony with their assignments, off the Angels would go to complete the tasks outlined and assigned to them by their unseen boss.

The shows droned on, the flaws of each magnified by their—as yet—incomplete status. Sexist jokes were scattered throughout each one of the episodes. It didn’t offend in the same way as did

Scent of a Woman

; these jokes were simply too lame to be measured on that scale. It didn’t matter. I wanted this job; my mind raced as I walked the eighth of a mile across the Fox lot to Spelling’s suite and my audition.

I was told to go right in. The offices were magnificent. It was the bungalow that had belonged to producer Jerry Wald during my earlier days at Fox. The suite had vaulted and beamed ceilings; there was a large fireplace and wet bar. Wald had been one of Hollywood’s legendary producers, said to be the prototype for Budd Schulberg’s

What Makes Sammy Run

. Now the office was Spelling’s. I entered the sanctum to find the mogul alone in the vast room and on the phone, saying, “I know, Fred. I agree with you.”

I learned later that the Fred on the other end of the line was ABC’s then-president, Fred Pierce. Spelling looked up, saw me standing at the door, and beckoned me toward a seat opposite his fine antique desk.

“You’re right, Fred,” he said. “We feel the same way.”

A long pause while he listened, then, referring to Fred Silverman, ABC programming chief, he continued. “Freddie’s right, it is embarrassing. But, Fred, Barney Rosenzweig is here now to take over the show, and we feel he’s going to turn this around.” Spelling went on a minute or so more as I beamed. The job was mine.

Aaron and I adjourned to another table in the office, away from his desk, so that his manservant could serve up lunch. It was for one. That was OK with me. I had to do all the talking anyway.

I launched into my spiel: “First of all, I do believe the show can be an enormous hit. I still feel strongly about the concept and the casting. Having said that, I’d like to focus on where I think mistakes have been made.”

Aaron busied himself with lunch but did motion me to go on.

“For openers,” I said, “the show begins on five minutes of static exposition. It’s cinematically uninteresting and all potentially boring. Worse, it violates one of the basic tenets of the private-eye genre, which is that the detective deals directly with the client—a character who is traditionally interesting, sometimes bizarre, and possibly dangerous. That doesn’t happen here because Charlie—who is never seen—meets the client off-stage and merely tells the Angels about it.”

I was revving up; Spelling continued his noontime repast.

“Remember those Bogart films where Sidney Greenstreet or whomever had to live in a refrigerated room or like an orchid in a hothouse?”

Aaron nodded. I went on. “By introducing such a character through our detectives, we not only make the exposition more interesting and visual, but we also give our detectives eye contact with the client. We give them a personal stake in all this. Our leads would no longer merely be mercenaries. The result is that we will like them better.” I had not so subtly made this a mutual project with a lot of “we”s and “our”s, not wanting to trust my status on the project to Spelling’s earlier pronouncement on the phone to the head of ABC.

“Finally,” I said, “the women should be more in charge and less the minions of someone we never see and therefore care about very little.”

I noticed Mr. Spelling’s brow furrow slightly. I plunged forward. “Let me give you an example of what I’m talking about. We would open, as we do now, on an action scene. Then, instead of going to Charlie’s speaker box, we cut to the home or office of the client. He or she has hired the Angels because of their reputation or a relationship with Charlie. After that scene (where the goals of the caper are now explained by an interesting character in a unique setting), we then cut to Charlie’s office and the speaker phone. There the Angels will outline to Charlie (instead of the other way around) what they learned and what each of them will do on the case. Charlie will then say: ‘Good thinking, Angels,’ and we’ll be off and running.”

I was pleased as Aaron approved my changes. He seemed grateful that someone actually had an idea about what might be wrong. I knew what I was doing was a lot more visual and certainly better storytelling. I also believed I was accomplishing a service for all concerned, including the audience, by making these working women brighter and more independent than my predecessors had.

Spelling summoned Leonard Goldberg, we shook hands, and I was on board. I then went on to meet my new story editor, Ed Lakso, who, although picked for me by Messrs. Spelling and Goldberg, was someone with whom, after an hour or so of preliminary discussions, I felt I could work with happily. We were in full harness in less than a day.

Part of our routine was to take long walks around the Fox lot, kicking around story and character ideas. I would come up with a scene, taking time to illustrate to Lakso how it might be staged, lit, and photographed. I’d go into incredible detail over this particular vignette (which might be the beginning, the middle, or the end of a story).

Now,” I said to Lakso on the first of these strolls, “the interesting thing is how did they get there and how do they get out?”

That would become Lakso’s job. Sometimes we’d work it out in tandem, sometimes we would alternate spinning webs for each other; mostly he did it on his own. He was extremely fast and facile.

The scripts started coming quickly, and they were good. The bosses thought they were great and sent memos (called Goldbergrams in those days) praising the work almost daily.

It was two weeks away from the production being turned over to our scripts when the first episode (completed by my predecessors) would air. I had volunteered my services to reedit what I had seen, but the offer was refused with thanks.

I wasn’t being altruistic. I was plenty worried that once the audience viewed these early episodes we might never get them to return. My concern was also how any critic could ever be brought back to the show so that we might demonstrate the effective changes we were making.

My concerns aside, the opening night ratings for Rick Husky’s version of the series were immense. The numbers were precedent setting. Hopefully, the drop off the following week would not kill us. There were some jokes from all quarters about the taste of the viewing public. The next week’s numbers on Rick’s second episode came out on the first day of production of the first episode under my aegis. They were higher than the previous week.

Charlie’s Angels

was a bona fide, major hit.

Mr. Goldberg was not being facetious when he then reversed himself, saying, “Let’s not make this show too good.” He thought he was onto something, however accidental. I would argue that the show was a smash in spite of the fact that it was awful, not because of it, but more and more I was being tuned out.

Goldberg believed the audience to be masturbating adolescent males. I felt the majority of viewers were young girls delighted to see fantasy role models on the screen, just as girls of my generation had been all too happy to read the exploits of Nancy Drew. Of course the girls wanted their heroines to be good looking. Didn’t Mr. Goldberg and I want Errol Flynn and Clark Gable to be handsome? I had been in that Westwood movie theater a few years before when

Cotton Comes to Harlem

made its debut in 1970. It was the first of the so-called

Blacksploitation

flicks, and I attended it with an audience primarily composed of people of color. They cheered the film. All their lives they had, along with me, applauded the exploits of John Wayne and Humphrey Bogart. Now, for the first time, someone who looked and sounded like them was doing all the star turns and getting the gal at the end. They loved it, and why shouldn’t they? It made perfect sense to me then, and it made the same kind of sense to me when I conceived

Cagney & Lacey

as well as when I argued with Spelling and Goldberg as to who the audience was for

Charlie’s Angels

.

The disputes were more than esoteric. My recollection is that they centered on the cheap, sexist jokes that my executive producers wanted inserted. I would fight and argue that it was a fundamental mistake to insult the very audience that was most loyally supporting the show. Kate Jackson, Jaclyn Smith, and Farrah Fawcett helped to make many of the arguments moot, as more and more they refused to say many of those double-entendre lines. Perhaps it was the critical comments they were reading about the show in the nation’s press; perhaps we simply underestimated them. Whatever it was, their consciousnesses were obviously being raised as well.

The mail, and ultimately several key articles by psychologists and sociologists, would confirm that the primary core of the

Charlie’s Angels

’ audience were teenage girls and young women. It didn’t matter. The arguments with my bosses continued to escalate. The honeymoon was definitely over.

There was more going on than was readily apparent. Despite protestations to the contrary and their allegiance to an ever-growing empire, Messrs. Spelling and Goldberg were having a tough time letting go of this project and, apparently, dealing with my popularity with the stars, saying at one point to Ms. Fawcett: “We don’t need anyone telling us how to make a hit of our show.” It was to get even pettier.

Editorial sessions were held on episodes, and I would not be notified. Projectionists would phone in sick and then appear at other parts of the lot to screen the show for either Mr. Spelling or Mr. Goldberg, excluding me from the process. These bosses could, of course, at any time squash me like a bug, but they actually appeared (at least from my perspective) to prefer this sort of psychological warfare to direct confrontation. Their operation was one where everyone was constantly off-balance. Chaos was the norm. I think the fact that they couldn’t make me perspire drove them both a little crazy.