Babe Ruth: Legends in Sports (5 page)

Read Babe Ruth: Legends in Sports Online

Authors: Matt Christopher

Around that time, George Herman “Babe” Ruth got a new nickname. Many of the fans living around Yankee Stadium were Italian.

They christened Ruth “Bambino,” which is Italian for “baby” or “babe.” New York sportswriters also used nicknames when describing

him, such as the “Colossus of Clout,” the “Mauling Monarch,” the “Prince of Pounders,” and the “Sultan of Swat.” They wrote

about him every day throughout the season. Every home run he hit was news, and so was every strikeout.

However, despite Ruth’s prodigious hitting, 1920 simply wasn’t the Yankees’ year. In August, Yankees

pitcher Carl Mays accidentally hit Cleveland Indians shortstop Ray Chapman in the head with a pitch. Chapman died, and after

the tragedy the Indians bounced back to take the pennant.

Ruth finished the season with a batting average of .376 with a record fifty-four home runs, a total that was higher than that

hit by all but two teams in baseball. There seemed to be no limit to what he could accomplish. Fans wondered if he would one

day hit sixty or even seventy home runs in a season.

His performance changed the game forever. After seeing what Ruth could accomplish, other players changed their approach at

the plate. Instead of just trying to make contact, more hitters began to swing from their heels like Babe Ruth. Before Ruth,

most batters hit home runs by accident. Now they tried to imitate Ruth. In a few years the home run would become more common.

Ruth soon cashed in on his fame. He starred in a movie called

Headin’ Home,

endorsed all sorts of products, and had a sports column written under his name by sportswriter Christy Walsh. He also went

on a long “barnstorming” trip, playing a series of exhibition games after the season and hitting home

runs against local teams before thousands of fans. Although organized baseball considered such tours illegal, Ruth didn’t

care. He was the most famous man in America, and he was making more money off the field than on it.

Of course, having lots of cash made it even more difficult for Ruth to stay out of trouble. Even though a new law known as

Prohibition, which banned the sale of alcohol, went into effect, that didn’t slow down Ruth, who spent much of his time in

what were known as “speakeasies,” illegal taverns that served alcohol. Life in the off season was one big party, and he turned

up for spring training covered in a thick layer of fat.

Ruth managed to get in shape in the spring and rapidly resumed his record hitting in 1921. Pitchers were afraid of him and

rarely gave him a pitch to hit. When they did, he knocked it out of the park.

Ruth and the Yankees took the American League by storm. At the end of the season Ruth had increased his home run record to

an incredible fifty-nine, and the Yankees won the pennant and the right to play the New York Giants in the World Series.

The Giants, led by feisty manager John McGraw,

were a terrific team. Unlike the Yankees, who waited for Ruth to hit home runs, the Giants still played baseball the old-fashioned

way, scratching and clawing for runs with bunts, base hits, and stolen bases. McGraw, considered the best manager in baseball,

promised everyone that his pitchers would shut down Ruth and the Yankees — a promise he made good on.

In a sense, the Yankees lost the series in the second game. After winning game one, the Yankees also took game two. But in

the middle of the game, Ruth, who had already walked three times, slid roughly into third base. As he twisted away from the

tag, he scraped his elbow.

Ruth shrugged off the injury, but in game three, a 13–5 Giant win, he scraped it again. By game four the elbow was infected

and badly swollen. By the next game, he could barely see the bat, and struck out three times, collecting his only hit on a

bunt. By then it was obvious he couldn’t continue to play because of the pain. For the rest of the series he made only one

appearance, as a pinch hitter.

Without Ruth, the Yankees were an average team.

The Giants stormed back to win the best-of-nine series five games to three. Despite his record 59 regular season home runs,

1921 ended in disappointment for Ruth.

After the season, baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis warned Ruth not to go on another barnstorming tour. Ruth ignored

him and went anyway. He felt as if he were bigger than the game.

He wasn’t. In December Landis suspended him for the first six weeks of the 1922 season.

Fortunately, the Yankees had earned so much money the previous season that they were able to acquire a number of other valuable

players, many from the Red Sox. Although they missed Ruth at the start of the season and sometimes struggled after his return,

the Yankees still had enough firepower and pitching to win the pennant.

However, Ruth was in a slump, at least for him. His batting average dropped to .315 and he hit “only” thirty-five home runs,

not enough to beat the new league leader, Ken Williams (of the St. Louis Browns), who hit thirty-nine.

Meanwhile, his behavior was once again a cause

for concern. When he returned to the team after the suspension, he was out of shape and never really got going. As the season

progressed, he spent night after night out on the town and often showed up at the ballpark bleary-eyed. One of his Yankee

roommates later said he didn’t really room with Ruth, he roomed “with his suitcase,” because Ruth was always out. On the field,

Ruth argued with umpires and was suspended several times for using bad language. Manager Huggins was powerless to change him.

Everybody was.

The Yankees met the Giants in the World Series for the second season in a row. This time, it wasn’t even close. The Giants

won in five games and Ruth was terrible, collecting only two hits.

At a banquet Ruth attended shortly after the end of the series, speaker after speaker lectured him about his behavior and

the way in which he had disappointed not only his teammates but the fans. New York Mayor Jimmy Walker said, “You have let

down the kids of America … they have seen their idol shattered and their dream broken.” Babe Ruth was humiliated and told

everyone, “I’m going back to my farm to get in shape.”

His career was at a crossroads and he knew it. If he didn’t do something fast, he wouldn’t be Babe Ruth anymore. This time,

he didn’t have anyone like Brother Matthias to bail him out. Ruth would have to help himself. It was time for him to grow

up, at least a little.

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER FIVE 1923–1925

1923–1925Ups and Downs

Babe Ruth kept his promise that winter. He returned to his Massachusetts farm, reuniting with Helen after a long separation,

and rarely ventured into the city. He stopped drinking, watched what he ate, and spent the winter doing farm work, skating,

chopping wood, and going for long hikes. He knew he had messed up in 1922 and was determined to prove that he was still the

best player in the game.

New York fans were looking forward to the 1923 season. At the cost of $2.5 million dollars, the Yankees had finally built

their own ballpark, Yankee Stadium. The new park in the Bronx was huge, capable of holding more than 70,000 fans, most of

whom were looking forward to seeing the Babe hit some home runs. The park designers had done what they could to satisfy them

by making sure the fence in

right field was short enough for Ruth to hit home runs with the same frequency he had at the Polo Grounds.

This year, the Bambino didn’t let them down. He showed up at spring training in tremendous shape, weighing 209 pounds. And

on opening day at Yankee Stadium he announced his return in dramatic fashion.

With the score 1–0 in favor of the Yankees in the fourth inning, Ruth came to bat. Boston pitcher Howard Ehmke let a ball

over the plate and Ruth gave it everything he had.

The ball soared deep and high to right field as everyone in the stadium stood and craned their necks to watch the flight of

the ball. When it finally came down it was ten rows deep in the right-field stands. Babe Ruth had hit the first home run in

Yankee Stadium! After the Yankee victory that day, a sports-writer referred to the stadium as “the House that Ruth Built,”

a nickname that has stayed with it ever since.

For the rest of the season there was no stopping New York. Although Ruth didn’t hit home runs quite as frequently as before,

ending the season with only

forty-one, he hit better than ever, staying above .400 for most of the year before finishing at .393. The Yankees won the

pennant by sixteen games over Detroit. Once again, they played the New York Giants in the World Series.

Thus far, Ruth had done everything in New York but help the Yankees win a championship. For all his accomplishments he knew

he wouldn’t really be considered a success until the Yankees won the series. Giants’ manager John McGraw entered the series

confident. After all, his pitchers had shut down Ruth in both 1921 and 1922 by throwing him outside curve balls. “The same

system,” he said, “will suffice.”

This time, however, Ruth was ready. He tripled in the first game, a Yankee loss, but in game two he broke loose with two long

home runs and narrowly missed a third. Although the Giants won game three 1–0, the Giants chose to walk Ruth twice rather

than let him hit. Then, in game four, Ruth and the Yankees took command and won the next two games to finally take the series

away from their crosstown rivals.

Yankee owner Jake Ruppert was ecstatic. “Now I have the greatest ballpark and the greatest team,” he said. Everyone already knew he had the greatest player — Babe Ruth.

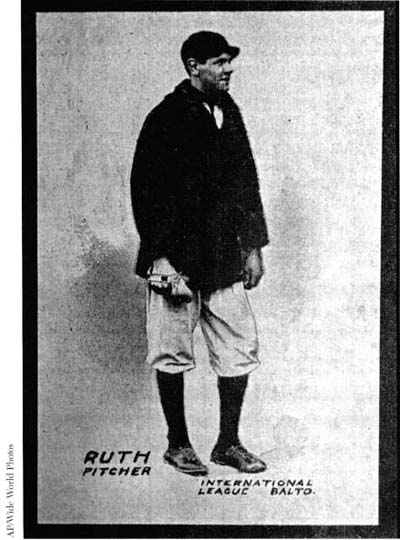

Before he was a Boston Red Sox pitcher and a New York Yankees slugger, Babe Ruth played for Baltimore in the International

League in 1914. This is his baseball card for that year.

An undated photo shows pitcher Babe Ruth in his Red Sox uniform. His ability to slug home runs had not yet been discovered

by the ball club.