Babel No More (32 page)

Authors: Michael Erard

Now surfacing, the hyperpolyglot tribe has long been lost to view—though hints of its existence pop out from time to time. Madeline

Ehrman, a research scientist now retired from the Foreign Service Institute’s School of Language Studies, observed accomplished language learners who scored a level 4 (out of 5 possible) on FSI proficiency tests in reading, speaking, or both. There are relatively few level 4s—it’s difficult to score so high (only 1 percent of people who have taken the test have ever scored as high as natives)—and

Ehrman found similarities among them. They tend to be meaning-oriented and pattern-seeking, and the majority of them were introverted intuitive thinkers. Using the labels of the Myers-Briggs personality type test, most of these were INTJs (Introverted, Intuitive, Thinking, Judging). This means they’re highly analytical people, introverted and intuitive, logical and precise, and prone to thinking in

terms of systems.

Ehrman also found an advantage for what she and a colleague have called “synoptic” learners, who acquire information unconsciously and “trust their guts.” A pure synoptic learner can quickly reach an intermediate level because their intuitions promote flexibility and discovery. On the downside, their skills tend to plateau. They might eventually be outperformed by people who

take conscious control of their learning, a group she labeled “ectenics.”

Most frequent among adult learners with very high levels of language proficiency were those whom Ehrman calls “synoptic sharpeners.” They blend the best of the synoptic—flexibility and openness—with an attention style, known as sharpening, where close attention is paid to minute differences among sounds, words, and meaning.

It’s not enough for them to call something “green”; the sharpener is precise and must identify it as “dusty olive.” They

notice

(which is a key skill that both Erik Gunnemark and Lomb Kató recommended). Synoptic sharpeners benefit from strategies that let them encounter language as it’s really used and, at the same time, notice linguistic details in those realms.

Whether you call these attributes

“cognitive style” or “personality,” there are elements of each that come with us when we’re born, and that we might pass to our descendants.

My survey provided a thumbnail view of this neural tribe. Most hyperpolyglots will claim that learning languages is easier for them than for others. They’ll also say that this is because they possess an innate talent. They don’t have high IQs; they aren’t

savants. If they seem reclusive, it’s not because they’re social cripples—I found some of them to be the most talkative shy people I’d ever met. Some hyperpolyglots are women, but far more are men, even though women tend to score higher on tests of verbal abilities than men. On my survey, of those who claimed more than six languages and said that learning languages was easier for them, 75 percent

were men. It’s worth noting that the Geschwind-Galaburda hypothesis doesn’t predict that 100 percent will be men, since the male hormones that affect brain development are present in biological females as well.

Some only read their languages; others aim to develop oral skills. Each hyperpolyglot has a variety of uses for his or her languages. Though the great majority seem to be autodidacts,

others are quite happy to learn with teachers and fellow students; their methods range widely. (See the

Appendix

for a list of methods from people who reported eleven languages or more.) Their lifetime repertoire of languages can be quite large, though the upper limit of fluently spoken, simultaneously accessible languages ranges from five to nine. More numerous latent languages can be “warmed

up” or “reactivated.” As I’ve described, having a dynamic repertoire that consists of both “active” and “surge” languages is a near-universal feature of the tribe.

They are also rare, even in highly motivated populations of professional language learners. Edgar Donovan, a US Air Force officer and a Defense Language Institute graduate in Persian-Farsi who has studied several other languages, sent

me his scores from official tests of his listening and reading proficiencies in fifteen languages. At DLI, these proficiencies are measured by the Defense Language Proficiency Test (DLPT), which ranks language abilities on a scale of 0 to 5. (Getting the highest rating, 5, means that you are “functionally equivalent” to the well-educated native reader or listener.)

Given that DLI is a high-pressure

school attended by ambitious people, you’d expect that many of the graduates would have multiple languages. Yet only 402 people out of the thousands who have attended

have ever scored 2 or above in both listening and reading in at least three languages. And while only fifty-three people had four high-proficiency languages, Donovan was one of only twenty people who had at least five high-proficiency

languages.

Only twenty out of thousands.

(True, there might have been others who hadn’t bothered to be tested, but given that more proven abilities could mean higher salaries or better postings, the number of people who didn’t bother is probably quite small.)

The online survey I designed captured information about two overlapping groups: those who reported that they knew six or more languages,

and those who said that learning a foreign language was easier for them than it was for others. There are two groups because a talent for learning isn’t always realized, and because not everyone with many languages found learning them easier. A more accurate picture emerges if potential is separated from actual achievements.

Figure 1

summarizes some of the facts about these two groups. Both are

mostly men between the ages of twenty-five and forty. It is not necessarily true that only English speakers become polyglots, though most of them grew up with only one language. It’s also not necessarily true that either talent or achievement is linked to IQ (the high skew probably stems from the fact that IQ was self-reported).

Figure 1

N = 390

Category 1: “I know >6 languages” N = 172

Gender

– 69.2% male

Age

– 44.8% 25 to 40

Mother Tongue

– 43 reported >1 mother tongue; 84 had English as (one) mother tongue

IQ

– 45.7% reported IQs over 140; 42% reported IQs 120–140

Origins

– 1 from South Africa, China, Australia; 2 from India; 167 from Europe, the US, Canada, or South America

Category 2: “I learn languages more easily” N = 289

Gender

– 65.6% male

Age

– 41.7% 25 to 40

Mother Tongue

– 53 reported >1 mother tongue; 162 had English as (one) mother tongue

IQ

– 35.3% reported IQs over 140; 50.4% reported IQs 120–140

Origins

– 1 from Vietnam, Pakistan, Singapore, China, India; 2 from Philippines; 3 from South Africa; 279 from Europe, US, Canada, or South America

I was also able to gather information about how many languages

people know.

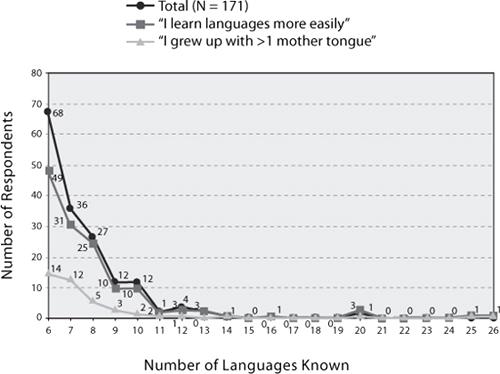

Figure 2

shows the distribution of language repertoire size among people who participated in the survey. I asked them, “How many languages do you say that you know (spoken and written)?”

Figure 2

shows that people who know more than six languages are rare, but not as rare as those who claim to know eleven or more, who represent the true modern extremes of human language learning.

Only two individuals had more than twenty (using their own definitions of “knowing” a language). This finding puts reports of Mezzofanti-size repertoires among modern hyperpolyglots into perspective. Over the entire curve, self-reported talent apparently makes a bigger contribution to language accumulation than does growing up bilingual. However, for the seventeen people with eleven or more languages,

six of them grew up with one mother tongue. Thus, we can say that early bilingualism made a larger relative contribution to their overall accumulation than for the whole group.

Here are a few more facts about extreme modern language accumulators. (There’s more available at

www.babelnomore.com

.) Of the seventeen, 82 percent of them were male. Five were in the United Kingdom, four were in the United

States, two each in Canada (one from Quebec) and Germany, and one each in India, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Latvia. They’re not particularly mobile; 62.5 percent said they live in the same place they grew up in. Twelve had English as one mother tongue and eleven said that English was now their dominant language. They claimed languages from an average of nine language families; as a group,

their language families ranged from five to seventeen. Assuming that they’re developing literacy skills, each one worked in an average of five writing systems, ranging from two to nine.

Given the size of their repertoires, it would have been surprising if they were able to learn only major world languages. Among these extreme accumulators, the bulk of these linguistic collections consisted of

European languages (representing the Romance, Germanic, Slavic, Finno-Ugric, Celtic, and Hellenic families), most of which are state languages (except for Macedonian, Latgalian, Welsh, Bavarian, Catalan, and Occitan, and historical versions of languages such as Old High German). Nevertheless, non-European languages were also represented: Arabic (in several regional forms), Hausa, Igbo, Afrikaans,

Farsi, Hindi/Urdu,

Kazakh, Kinyarwanda, Hawaiian, Japanese, Mandarin, Cantonese, Mongolian, Vietnamese, Malay/Indonesian, Korean, Southern Min, Wu, Thai, Hindi, Marathi, Gujarati, Sanskrit, Innu-aimun, and Cree. Apart from Farsi, Japanese, Mandarin, Cantonese, Korean, Thai, and Hindi, all the languages were reported by only one person apiece. Overall, there were only two Native American languages,

Innu-aimun and Cree.

Figure 2. Polyglot language repertoires.

I asked them in what order they learned these languages. A common assumption is that language accumulators learn within language families in order to “rack up numbers,” but my analysis shows this isn’t strictly true. From language to language, they were more likely to move between different language families (e.g., English → Arabic) than within the same

family (e.g., English → German → Dutch). About a quarter of the time, they studied languages from families they’d encountered before. Another interesting pattern was that Asian languages, nonstate languages, and languages with smaller populations of speakers were more apt to be learned later than earlier.

All of them said that learning languages was easier for them than for others. The survey

asked them why. Sixty-two percent said it’s due to an

innate talent; 69 percent said it’s because they’re more motivated; and 88 percent said it’s because they like languages. In other studies with similar findings, motivation is treated as a personality trait, which means you can’t predict who will and who won’t have it. To the contrary, the neural tribe theory, borrowing from Ellen Winner’s

descriptions of gifted children, suggests that you’re born with the capacity to be motivated to learn foreign languages. How that capacity is developed is a matter of biographical detail and historical circumstance.

In the stairwell of Gregg Cox’s house in Bremen, Germany, I’d seen the plaque from

The

Guinness Book of World Records

: “Gregg M. Cox of Oregon, USA, the Greatest Living Linguist,

is able to read, write and speak 64 languages, 11 different dialects, speaking 14 fluently.” It had once hung in the hallway, but his wife, Sabine, moved it to the staircase because her clients (she’s a cosmetologist) always wanted to talk about her husband. “You don’t want to tell every customer your entire history and who you’re married to,” Sabine said. “I mean, I’m proud, but . . .” Her sentence

trailed off.

The three of us were standing in Cox’s office; she was talking while Cox, a short, bald man, rummaged through papers in his desk.

“I got tired of it, so I hung it in a different place,” she said. “I go shopping sometimes,” she said wearily. “They say, ‘Cox, oh, are you his wife?’ I say yes.”

“Do they expect you to speak a lot of languages?” I asked.

“I get that a lot,” she replied.

“I say, I only speak two languages. But then I say, it doesn’t matter how many languages I speak, because he doesn’t understand me anyway.”

When Cox and I sat down to talk again, I asked him if there were any myths about hyperpolyglots. He immediately replied, “That they can jump back and forth between all their languages. That’s the biggest myth. I’ve met several other polyglots, and we’ve been

able to bounce back and forth in seven or eight languages, but not further than that,” he said. “The most languages that I’ve ever had back and forth with somebody was seven.” (I can attest that I heard Cox speak English, German, and Spanish in our several days together.)