Ballad (12 page)

James

Because I was not a

real

music student and because Sullivan sucked at organizational skills, we had to meet for my piano lesson in the old auditorium building. Turns out the practice rooms were filled to capacity at five o’clock on Fridays, by real piano players and real clarinet players and real cellists and all their real teachers and ensemble leaders.

So instead, I picked my way over to ugly Brigid Hall. To prove that Brigid was no longer a useful member of the Thornking-Ash environ, the grounds people had let the lawn between Brigid and the other academic buildings get autumn crunchy and allowed the boxwoods and ivy to take over the dull, yellow-brick exterior. It was a message to all visiting parents:

Do not take pictures of this part of the campus. This building has been deemed too ugly for academic use

.

Don’t think we didn’t notice.

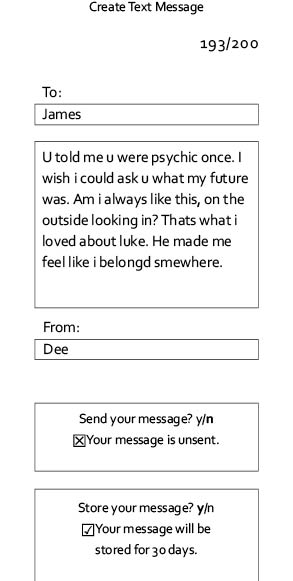

On the walk over, my phone beeped in my pocket. Pulling it out, I saw a text message from Dee. When I opened it, the first words of text I saw were

James im so sorry

and I felt sick to my stomach and deleted it without reading any further. I shoved the phone back into my pocket and headed around the side of Brigid Hall to the entry.

The door was coated in peeling red paint that seemed somehow significant. I didn’t think there were any other red doors on campus. Like me, a loner. I punched my knuckles lightly against the door knob in solidarity. “You and me, buddy,” I said under my breath. “One of a kind.”

I let myself in. I had entered a long, thin room, populated by old folding chairs all pointed attentively toward a low stage at the other end of the building. It smelled like mold and the old wood of the floor and the ivy pressed up by the frosted glass windows. On the stage, recessed lights illuminated a grand piano that was as old and ugly as the building itself. The whole thing was a crash course in all that was best forgotten about 1950s architecture.

Sullivan sat at the piano, knobby figures toying with the keys. Nothing mind-blowing, but he knew his way around the keyboard. And the piano, for what it was worth, didn’t sound nearly as bad as it looked. I walked up through the folding chair audience, grabbing one of the front-row chairs and bringing it onto the stage with me.

“Salutations, sensei,” I told him, and dropped my backpack onto the chair beside the piano. “What a lovely creation that piano is.”

“Isn’t it though? I don’t think anybody remembers that this building is here.” Sullivan played “Shave and a Haircut” before getting up from the bench. “Strange to think this used to be their auditorium. Ugly little place, isn’t it?”

I noted the detachment. Not “

our

auditorium.” Sullivan was frowning at me. “Feeling all right?”

“I didn’t sleep much.” A understatement of cosmic proportions. I wanted nothing more than the day to be done so that I could fall into my bed.

“You mean, other than what you did in my class,” Sullivan said.

“Some would argue that recumbent listening is the most effective.”

He shook his head. “Right. I’ll be looking for evidence of its efficacy on your next exam.” He gestured to the bench. “Your throne.”

I sat at the piano; the bench creaked and shifted precariously. The piano was so old that the name of the maker was mostly worn away from above the keyboard. And it smelled. Like ground-up old ladies. Sullivan had put some sheet music up on the stand; something by Bach that I’m sure was meant to look simple but had way too many lines for pipe music.

Sullivan turned the folding chair around and sat on it backwards. His face was intent. “So you’ve never played piano before.”

The memory of Nuala’s fingers overlaying mine was somehow colored by the memory of last night; I tightened my fingers into a fist and released them to avoid shivering. “I tinkered with it once after we talked. Otherwise”—I ran my fingers over the keys and this time, struck by the memory of Nuala, I did shiver, just a tiny jerk—“we’re virtually strangers.”

“So you can’t play that music up there on the stand.”

I looked at it again. It was in a foreign language—like hell could I play it. I shrugged. “Greek to me.”

Sullivan’s voice changed; it was hard now. “How about the music you brought with you?”

“I don’t follow.”

Sullivan jerked his chin toward my arms, covered by the long sleeves of my black

ROFLMAO

T-shirt. “Am I wrong?”

I wanted to ask him how he knew. He could’ve guessed. The writing on my hands, equal parts words and music, disappeared beneath both sleeves. I might’ve had them pushed up earlier, in his class. I couldn’t remember. “I can’t play written music on the piano.”

Sullivan stood up, gesturing me off the bench and taking my place. “But I can. Roll up your sleeves.”

I stood in the yellow-orange stage lights and pushed them up. Both of my arms were dark with my tiny printing, jagged strokes of musical notes on hurriedly drawn staffs. The notes went all the way around my arms, uglier and harder to read on my right arm where I’d had to use my left hand to write. I didn’t say anything. Sullivan was looking at my arms with something like anger, or horror, or despair.

But the only thing he said was, “Where is the beginning?”

I had to search for a moment to find it, inside my left elbow, and I turned it toward him, my hand outstretched like I was asking him for something.

He began to play it. It was a lot

older

-sounding than I remembered it being when I’d sung and hummed it with Nuala. All modal, dancing right between major and minor key. It kicked ass a lot more than I remembered too. It was secretive, beautiful, longing, dark, bright, low, high. An overture. A collection of all the themes that were to be worked into our play.

Sullivan got to the end of the music on my left arm and stopped. He pointed to his flat leather music case leaning against the piano leg. “Give me that.”

I handed it to him and watched as he reached inside and pulled out the same tape recorder he’d brought to the hill that day. He set it on top of the piano and looked at it as if it contained the secrets of the world. Then he pressed play.

I heard my voice, small and tinny: “You weren’t recording before now?”

Sullivan’s voice, sounding very young and fierce when not attached to his body: “Didn’t know if I’d have to.”

A long silence, hissing tape, birds singing distantly.

Then, Nuala’s voice: “Don’t say anything.” I didn’t immediately realize what it meant, that I was hearing Nuala’s voice coming out of the recorder. She continued. “You’re the only one who can see me right now, so if you talk to me, you’re going to look like you were retained in the birth canal without oxygen or something.”

Sullivan reached up and hit

stop

.

“Tell me you didn’t make the deal, James.”

His voice was so grave and taut that I just said the truth. “I didn’t.”

“Are you just saying that? Tell me you didn’t give her a single year of your life.”

“I didn’t give her anything.” But I didn’t know if that was true. It didn’t

feel

true.

“I’d love to believe that,” Sullivan said, and now his voice was furious. He grabbed my hand and wrenched it so that I was staring at my own skin, inches from my face. “But I have to tell you, they don’t give you

that

for nothing. You’re my student, and I want to know what or who you promised to get this, because it’s my responsibility to keep stupid, brilliant kids like yourself from getting killed, and I’m going to have to clean things up now.”

I should’ve had something to say. If not witty, than just something.

Sullivan released my hand. “Were you not good enough on your own? Best damn piper in the state and you had to strike a deal for more? I should’ve known it wouldn’t be enough. Maybe you thought it would only affect you? It

never

affects just you.”

I jerked down my sleeves. “You don’t know what you’re talking about. I

didn’t make a deal

. You don’t know.”

But maybe he did know. I didn’t know what the hell he knew.

Sullivan looked at the partially rubbed-off letters above the keyboard and clenched and unclenched his hand. “James, I know you think I’m just an idiot. A musician who sold out his teen dreams to become a junior-faculty foot-wipe at a posh high school. That’s what you think I am, right?”

Nuala, who actually read my mind, would’ve been able to word it better, but he was still pretty close for a non-supernatural entity. I shrugged, figuring a non-verbal answer was really the best way to go.

He grimaced at the piano keys, running his fingers over them. “I know that because I

was

you, ten years ago. I was going to be somebody. Nobody was going to stand in my way, and I had a bunch of people at Juilliard who agreed with me. It was my life.”

“I’m not a fan of morality tales,” I told him.

“Oh, this one has a twist ending,” Sullivan said, voice bitter. “They ruined my life. I didn’t even know They existed. I didn’t even stand a chance. But

you

do. I’m telling you right now, they use people like us to get ahead. Because we want what They have to offer and we don’t like the world the way it is. But what you have to understand, James, is just because we want what They have and They want what we have, doesn’t mean we end up with something we like. We don’t.”

He shoved back from the piano and got up from the bench. “Now sit down.”

I didn’t know what else to say, so I gave him part of the truth. “I don’t really want to play the piano.”

“I didn’t either,” Sullivan said. “But at least it’s not an instrument they particularly care for. So it’s a good one for both of us to be playing. Sit down.”

I sat down, but I didn’t think Sullivan knew as much about Nuala as he thought he did.

James

When I pulled the six-pack out of my backpack, Paul looked as if I’d laid an egg. I set it down on the desk next to his bed and turned the chair around backwards before sitting on it.

“You still want to get drunk?”

Paul’s eyes were twice as round as usual. “Man, how did you get that?”

I reached behind me to get a pen from the desk and wrote

the list

on it without quite knowing why. I felt better after I did. “The archangel Michael came down from on high and I asked him, ‘Lo, how can I getteth the stick from my friend Paul’s ass?’ and he said, ‘This ought to go a long way.’ And gave me a six-pack of Heineken. Don’t ask me why Heineken.”

“Is that enough to get me drunk?” Paul was still looking at the six-pack as if it were an H-bomb. “In the movies, they drink forever and never get drunk.”

“A beer virgin like yourself won’t.” I was acutely pleased that I didn’t have to worry about Paul vomiting, thanks to foresight on my part. I liked Paul a lot, but I didn’t think I wanted to dedicate any of the minutes of my life to cleaning up his barf. “And it’s all for you.”

Paul looked panicked at that. “You aren’t drinking?”

“Anything that is mind-altering makes me nervous.” I dumped the pencils and pens from the mug that served as our pencil can; they clattered and rolled every which way on the desk. I handed Paul the pencil can.

“That’s because you always like to be in control of everything,” Paul said, weirdly observant. He looked into the mug in his hands. “What is this for?”

“In case you’re shy about drinking out of a bottle.”

“Dude, there’s like, pencil crap and who knows what in here.”

I handed him a bottle of beer and turned back to the desk, picking up one of the markers that I’d dumped from the pencil can and finding a scrap piece of paper. I scrawled busily, filling the room with the scent of permanent marker. “Sorry to offend, princess. Bottom’s up. The pizza should be here soon.”

“What are you doing?”

“I’m ensuring our privacy.” I showed him the sign I’d created.

Paul is feeling delicate. Please do not disturb his beauty sleep.

xoxo Paul

. I’d put a heart around his name too.

“You bastard,” Paul said, as I stood up and opened the door long enough to tape it to the outside. Behind me, I heard the click of him opening the bottle. “Dude, this smells

rank

.”

“Welcome to the world of beer, my friend.” I crashed on my bed. “Like all vices, it comes with a warning that we usually ignore.”

Paul rubbed at the condensation on the outside. “What happened to the labels?”

He didn’t have to know how long it had taken me to remove all of the labels and swap the bottle caps. Labor of love, baby. “You get them cheaper when you buy the ones that are mislabeled or the labels got damaged.”

“Really? Good to know.” Paul made a face and took a swig. “How will I know I’m getting drunk?”

“You’ll start getting as funny as me. Well, funnier than you usually are, anyway. Every little bit helps.”

Paul threw the bottle cap at me.

“Drink one before the food comes,” I said. “It works better on an empty stomach.”

I watched Paul drink half the bottle and then I jumped up and went to the CD player I’d brought with me. “Where are your CDs, Paul? We need some music for the event.”

Paul gulped down the other half, choking a bit on the last of it, and pointed vaguely under his bed. I handed him another bottle before laying on the floor next to his bed and preparing myself for the worst.

I bit back a swear word with a great force of will. Nuala’s eyes crinkled into evil humor, inches away from mine, glowing from beneath Paul’s bed.

“Surprise,” she said.

You didn’t surprise me

, I thought.

“Yeah, I did. I can read your thoughts, remember?” She pointed to the bottom of the mattress. “That’s pretty funny, what you’re doing. Is that real beer?”

I lifted my finger to my lips and silently made my lips go

shhh

. Nuala grinned.

“You’re not a good person,” she said. “I like that about you.”

She pushed Paul’s CD binder to me and rested her freckled cheek on her arms. “See you later.”

I stood up with his CDs and looked over to see how he was faring. He seemed more chipper already. God bless vanishing inhibitions. “So what have you got in here?” I asked Paul, but I started paging through without waiting for his answer. “These are all

dead

guys, Paul.”

“Beethoven’s not really dead,” Paul pointed at me with the bottle. “That’s just a rumor. A cover-up. He’s doing weddings in Vegas.”

I grinned. “Too right. Ohhh, Paul.

Paul

. What the crap. You have a Kelly Clarkson CD in here. Tell me it’s your sister’s. Tell me you

have

a sister.”

Paul was a little defensive. “Hey, she has a good voice.”

“God, Paul!” I flipped through more of the CDs. “Your brain is like a cultural wasteland. One Republic? Maroon Five? Sheryl

Crow

? Are you a little girl? I don’t even know what to put on that won’t make me develop breasts and start craving chocolate.”

“Give it to me,” Paul said. He took the CD case and pulled one out. “Get me another bottle while I put this on. I think it’s working.”

So that was how we happened to be listening to Britney Spears “Hit Me Baby One More Time” when the pizza guy delivered our sausage-and-green-peppers, extra-cheese, extra-sauce, extra-calories, extra everything.

Pizza guy raised his eyebrows.

“My friend is having his period,” I told the pizza guy, and handed him his tip. “He needs Britney and extra cheese to get him through it. I’m trying to be supportive.”

Paul was singing along by the time I got the box open and ripped the pieces apart. I handed him a piece of pizza and took one for myself. “This is awesome, dude,” he told me. “I can see why college kids do it.”

“Britney Spears, or beer?”

“

E-mail my heart

,” Paul sang at me.

I’d created a monster.

“Paul,” I said. “I was thinking some more about this metaphor assignment.”

Paul studied the string of cheese that led from his piece of pizza to his mouth. He spoke carefully to avoid breaking it. “How it sucks?”

“Right on. So I was thinking we could do something else. Together.”

“Dude, I looked them up online. They’re like, forty-five dollars.”

I lifted up the top layer of cheese on my slice of pizza and scraped some of the sauce off. “What are you talking about?”

Paul waved a hand at me. “Oh. I thought you were talking about buying one of those papers online. After Sullivan mentioned it, I looked it up. They’re forty-five bucks to download.”

I made a note to remind Sullivan that we students were young and impressionable. “I actually meant doing something entirely different for the assignment. Would you really buy a paper online?”

“Nah,” Paul said sadly. “Even if I did have a credit card. It’s a sad statement about my lack of balls, isn’t it?”

“Balls isn’t buying someone else’s term paper,” I assured him. “When you’re sober, I have something I want you to read. A play.”

“

Hamlet

’s a play,” Paul observed. He held out his hand. “Lemme read it now.”

I grabbed the notebook from my bed and tossed it to him.

Paul scanned the text of

Ballad

while singing along with Britney. He paused just long enough to say, “This is some good shit, James.”

“I don’t have any other kind,” I said.

“Sullivan!” Nuala warned from under the bed. I looked sharply in the direction of the bed and then headed to the door just as the knock came. I opened the door and stepped out into the hall, shutting the door behind myself.

Sullivan’s expression was pointed. “James.”

“Mr. Sullivan.”

“Interesting choice of music you two have chosen for tonight.”

I inclined my head slightly. “I like to believe that our time at Thornking-Ash has invested in us a deep appreciation for all musical genres.”

Inside the room, Paul hit a really high note. I think the kid had perfect pitch. He’d really missed his calling. He shouldn’t be playing the oboe, he should be touring nationally with Mariah Carey.

“Dear God,” Sullivan said.

“Agreed. So what brings you to our fair floor?”

Sullivan craned his neck to see the sign I’d put on the door. “Pizza. Delivery boy said it looked like one of you was drinking something that looked an awful lot like beer.”

“See if I ever tip him again, if he’s going to trill like a canary first time anyone looks at him funny.”

Sullivan crossed his arms. “So is that why Paul is singing high E over C in there? I know

you

haven’t been drinking. You don’t smell like it and you are definitely just your usual charming self.”

I smiled congenially at him. “I can tell you quite honestly that neither of us is drinking alcohol.”

He narrowed his eyes. “What are you up to?”

I lifted my hands as if in surrender. “He wanted to get drunk. I wanted to see him loosen up. Three bottles of non-alcoholic beer later, and I think”—I paused, as Paul tried for another high note and failed miserably—“I think both of us are happy with the results while being, surprisingly, on this side of legal.”

Sullivan’s mouth worked. He wouldn’t reward me with a smile. “Shocking, considering the person who was the genesis of this plan. And how did you fool Paul?”

“The guy at the bar in town was kind enough to let me have a Heineken box and some caps. I swapped out the caps on six non-alcoholic beers and stripped the labels with some story about discounts for Paul. I think the bartender was a very good sport. Like some of my teachers.” I raised an eyebrow at him, waiting to see if he was going to rise to it.

“The machinations involved are incredible; it pains me to consider how much of your free time this involved. Well, far be it from me to destroy an evening based on camaraderie, deception, and fake beer.” Sullivan looked at me and shook his head. “God help me, James, what the hell are you?”

I blinked back up at him. “Dying to get back in there and see if I can get Paul to wear his underwear on his head is what I am.”

Sullivan wiped a smile off his face with his hand. “Good night, James. No hangovers, I trust.”

I grinned at him and slid back into the room, shutting the door behind me.

Thanks, Nuala

.

“No problem,” Nuala replied.

“Who was that at the door?” Paul asked.

“Your mom.” I handed him a fourth bottle. “You’re going to have to pee like a racehorse.”

“Do you think racehorses pee more than other horses?” Paul asked. “It doesn’t seem like they ought to, but otherwise, why isn’t it just ‘pee like a horse’?”

I took another piece of pizza and lay down on the floor next to his bed. It was several degrees cooler on the floor, and in the draft, I could smell Nuala’s flowery summer breath strongly. “Maybe they drink more water. Or maybe nobody gives a crap if other horses pee.”

“Gives a crap about pee,” echoed Paul with a laugh.

I laughed too, for an entirely different reason, and saw the line of Nuala’s sarcastic smile underneath the edge of the bed.

You could be anywhere and he couldn’t see you. Why under the bed?

“’Cause I wanted to scare the shit out of you,” Nuala said.

I offered her my piece of pizza, and she gave me a really weird, shocked look and then shook her head. It made me think about the old faerie tales, how if you ate any faerie food you were offered in faerieland you had to stay there forever. Except it could work in reverse, I guessed. Above us, the CD changer switched to the next CD, one of my Breaking Benjamin albums.

“Now this is real music,” I told Paul.

On the bed above, Paul thumped his foot in time with the beat. “Britney’s real too, dude. But this is just a little more real.” He paused. “Dude, I think you’re the coolest friend I’ve ever had.”