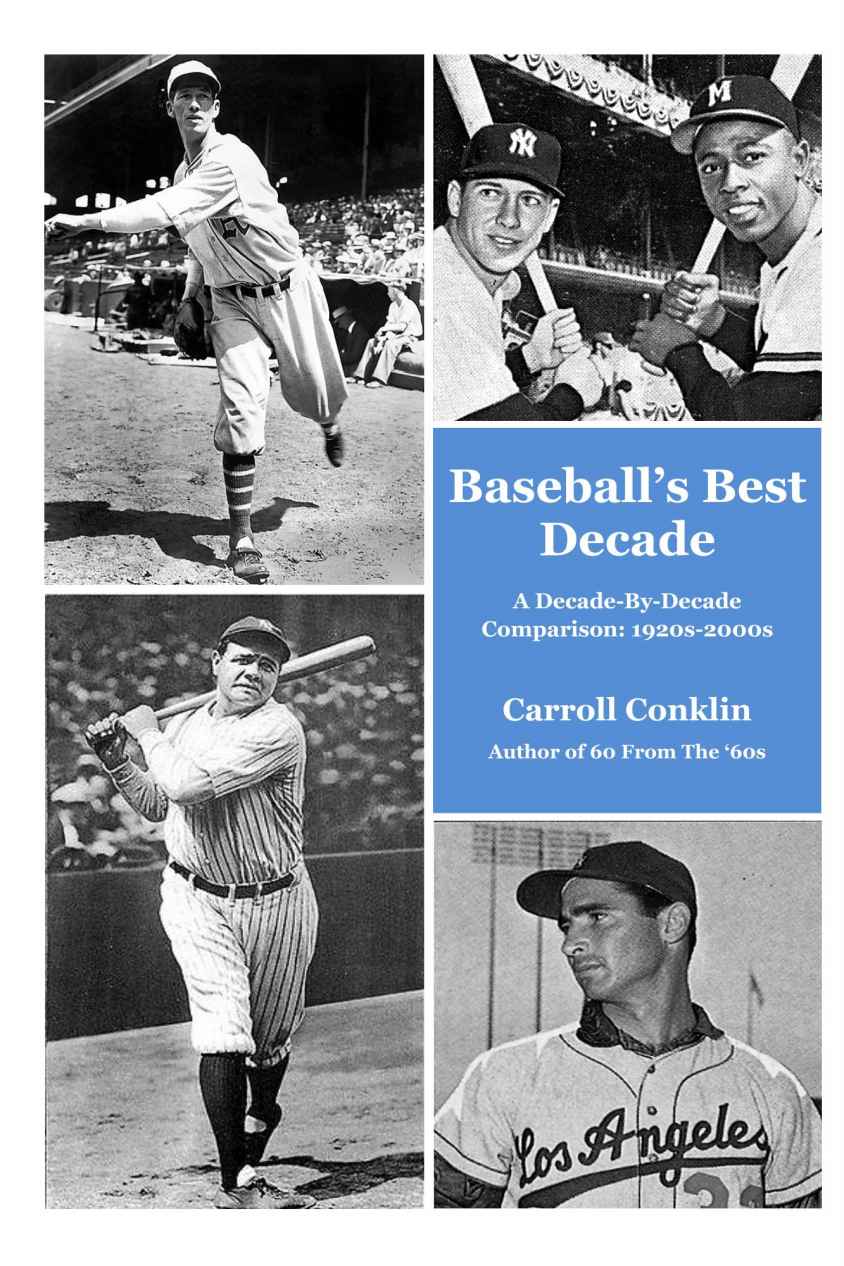

Baseball's Best Decade

Read Baseball's Best Decade Online

Authors: Carroll Conklin

Baseball’s

Baseball’s

Best Decade

A Decade-By-Decade Comparison: 1920s-2000s

Carroll Conklin

Published by

Bright Stone Press

© 2014

Carroll C Conklin

All Rights Reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

Photo Credits

–

Topps Chewing Gum Inc.

,

Library of Congress,

Baseball Digest

,

Jay Publishing, Inc.

,

Fleer Corporation

,

Leaf Brands

,

NU-CARD

,

Bazooka Gum

,

Post Cereal

,

Jell-O, Cincinnati Reds Postcards

,

Bowman Gum Company

,

Exhibit Supply Co.

,

Golden Press

,

Kashin Publications

,

Old Gold Cigarettes

,

Time, Inc.

,

Willard Chocolate

,

Gum Products, Inc.

,

Berk Ross

,

Goudey

,

Worch Cigar

,

Metropolitan Studios

,

Butterfinger

The photos used in this book are in the public domain because their sources were published in the United States before January 1, 1923, or were published between 1923 and 1963 with a copyright notice and the copyrights were not renewed. A search of the The United States Copyright Office Online Catalog for records from 1978 to the present revealed no renewals for the above cited photo sources within the required period for filing.

Contents

Foreword

Baseball’s Best Decade: The Teams, the Players,

the Numbers

The Hits Just Keep On Comin’

Comparing the Hitters, Decade By Decade

Switch on the Power

Comparing the Power Hitters, Decade By Decade

Call to Arms

Comparing the Pitchers, Decade by Decade

All Together Now

Comparing the Major Leagues, Decade by Decade

The Real Golden Age Must Be …

You Decide

Foreword

Baseball’s Best Decade:

The Teams, the Players, the Numbers

More than any of the major sports, baseball is tied to its history. Any player’s greatness today is measured almost automatically against the performances of the past.

No baseball fan can long be an admirer of today’s game without some familiarity of legends long gone. Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb, Cy Young, Ted Williams, Joe DiMaggio – their presence in the game remains. Even the diamond stars of 40 and 50 years ago hold a place in contemporary fans’ imagination. What baseball fan hasn’t heard of Mickey Mantle, Willie Mays, Hank Aaron or Bob Gibson?

In professional football or basketball, the link with the past is just not as strong. The stars of the past in those sports are names whose accomplishments have less of a connection to the feats of today’s stars. For the most part, once their records were broken, their names drifted into the misty memory of only those individuals who were lucky enough (and old enough) to have actually seen them play.

Take the case of the man who may have been the greatest running back in NFL history. I am old enough to have witnessed Jim Brown’s amazing season of 1963, when he rushed for 1,863 yards (the NFL record at the time) in a 14-game season. He was a huge fullback in his day, as big and as strong as any linebacker and as big as

some defensive linemen. Today there are quarterbacks who are bigger. And Division I college football linemen are generally bigger than Jim Brown in his prime. His speed and power allowed him to do incredible things that are still in my memory, things which lack the excitement of their moment when they are experienced now only in black and white archival films.

Jim Brown

Today’s fans can hear about Jim Brown, but they can’t experience for themselves how incredible he was. And as his records have been topped, repeatedly now, by bigger backs in longer seasons, Brown has become a legendary name that today’s generation of fans, especially the younger ones, have little if any attachment to, and for good reason: the Jim Brown who thrilled NFL fans a half-century ago could not do it the same way today. He might be just as good, but he wouldn’t be the same.

That reality also holds

true for NBA legends. The game of pro basketball has been transformed so dramatically over the last 50 years that’s it’s hard to imagine a George Mikan or Bob Pettit being as dominant today as they were in their prime. Bill Russell and Wilt Chamberlain, two of the greatest centers to have ever stepped onto a hard court, would have to be different players today. Talented as they were, it’s difficult to imagine them wielding the same prowess in today’s NBA.

Maybe today’s professional football and basketball players are,

overall, better than the players of a half-century ago. They are certainly bigger, faster and generally more athletic. But more skilled? Who knows? And how can you compare? Both of these sports are so different from their mid-Twentieth Century versions that such comparisons are almost meaningless.

Baseball

is a different animal. In general, today’s major league players are almost certainly bigger, faster and more athletic than the sum of major leaguers decades ago. But they are also, still, mostly normal-sized human beings. And the game, with the exceptions of the introduction of the designated hitter and the calculated management of relief specialists, has changed hardly at all in both its rules and execution. Comparing teams and players from different eras makes more sense in baseball than in any other sport.

Jackie Robinson

The most important change in baseball during the Twentieth Century was the breaking of the color barrier in 1947. The influx of African-American and Latin players into major league baseball vastly expanded the talent pool, and raised the standards for greatness in every aspect of the game. That is the one reason why you will see such a dramatic shift in player performance, as reflected by the statistics compiled in this volume, from the 1950s on. As great as the best players from the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s were, their competition (it could legitimately be argued) was no match for the level of talent all players faced in the integrated major leagues.

In fact, it could be argued that the first expansion of the two major leagues in the early 1960s didn’t dilute the talent at the major league level (as subsequent expansions almost certainly have done). That first expansion, from 16 to 20 teams, actually

raised

the level of play by introducing more great players into the major league arena. (Of course, if you were a New York Mets fan in the early 1960s, you might have trouble accepting that premise based on watching your home team day in and day out.)

While baseball talent improved starting in the 1950s, the game remained essentially the same. Still three strikes to a batter, and three outs to an inning (with no time limit). It may be difficult to imagine a Paul Hornung or Y.A. Tittle performing as effectively in today’s NFL, or a Jerry West or Willis Reed being as dominating as they wer

e 40 years ago in today’s NBA. Yet applying the same inter-era mind stretch to baseball is so much more accommodating, and more intriguing. How would Warren Spahn do facing a Miguel Cabrera four times in a game? How would Jimmie Foxx fare against a Clayton Kershaw or, in his prime, Greg Maddux? Real baseball fans would treasure those kinds of match-ups, far-fetched only by the limits of human mortality. Comparison of players, teams and even decades make sense in history-rich baseball more than in any other major sport.

A Golden Age for Baseball?

I grew up with baseball in the 1960s, hearing all the while that “Baseball’s Golden Age” was the 1920s – the age of Babe Ruth and

Lou Gehrig and Walter Johnson and Rogers Hornsby and the New York Yankees of “Murderers’ Row” fame. In my adolescence, as I was discovering the beautiful intricacies of the national pastime while able to follow the exploits of living legends like Mays and Mantle and Koufax and Aaron, what was drummed into my head was the “indisputable” acceptance of the 1927 Yankees as the greatest baseball team ever. I took that as gospel, at the time. Somebody knew more about baseball than I did, and besides, I never had the opportunity to witness those players and teams.

Today I’m not buying it. A lot of baseball has happened since I starting following the game as a kid, and it’s hard to believe that baseball reached its pinnacle nearly a century ago, and hasn’t been topped since. The integration issue aside, the numbers simply don’t support that claim. When you look at the numbers on a decade-by-decade basis (as this book does), the pitching alone doesn’t stand up to what I w

itnessed during the 1960s. For that matter, major league pitching pre-World War II just doesn’t compare to any decade since the 1960s (at least until you arrive at the bloated ERAs of the 2000s).

Could there be such a thing as a

real

golden age of baseball? It’s a subjective call, even with the wealth of statistics available for each decade. If you search any combination of “baseball” and “golden age” in Google, you’ll find someone claiming that each decade from the 1950s to the present as the real golden age of baseball – even someone making that claim for the war-depleted talent of the 1940s.

What I have tried to do here is to throw some statistical light on the matter of which decade best qualifies as baseball’s

real

golden age. If you’ve visited my Web site (www.1960sbaseball.com), you know clearly where I stand: that the 1960s, despite having the lowest combined batting average of any decade since 1920, represent the real golden age of baseball based on the combination of great pitchers dueling great hitters and 10 exciting seasons. But that’s just my opinion.

I have compiled decade-by-

decade statistics in each of 4 performance categories: hitting, power hitting, pitching and the major leagues’ combined statistics. For the first three categories, you’ll find listed the top five players and teams for each decade. The combined statistics list the decades in order, both for totals and for designated averages. Why by decade? Because this approach does identify those players who demonstrated consistent excellence over an extended period of time, and generally eliminates players with one or two outstanding seasons only.