Baseball's Hall of Fame or Hall of Shame (34 page)

Of the three men, Brown appears to be the most qualified. Certainly, his endorsement by

The Pittsburgh Courier

is a point in his favor. Being included with the likes of Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige, Buck Leonard, and Cool Papa Bell is most impressive. Mendez also had an outstanding reputation, and he received very high praise from those fortunate enough to have seen him play. But he was an exceptional pitcher for only six seasons. Furthermore, he achieved much of his glory playing in the Cuban Leagues. As a result, one can only guess as to the level of competition he typically faced. Therefore, Mendez’s selection would have to be considered the most questionable of the three. Yet, as is the case with all the former Negro League stars, the limited availability of statistical data surrounding the careers of Brown, Cooper, and Mendez makes it extremely difficult to find fault with their 2006 selections by the Veterans Committee.

Ted Lyons

Ted Lyons’ career won-lost record of 260-230 left him with the third lowest winning percentage (.531) of any starting pitcher in the Hall of Fame. However, when one considers that, in Lyons’ 21 seasons with the Chicago White Sox, the team finished out of the second division only five times, his record becomes far more impressive.

Lyons had the misfortune of joining the White Sox in 1923, just three years after several of the team’s best players were banned for life by Commissioner Landis for throwing the 1919 World Series. The commissioner’s edict relegated the Sox to second-division status for the next several seasons, and, unfortunately for Lyons, they remained a weak team throughout much of his career.

Yet Lyons still managed to win 260 games, and was a 20-game winner three times. His first 20-win season was in 1925, when he finished 21-11 with a 3.26 ERA and a league-leading 5 shutouts. Two years later, he had arguably his finest season, leading the league with 22 wins, against 14 losses, compiling a 2.84 ERA, and also leading the league with 30 complete games and 307 innings pitched. He finished third in the league MVP voting that year. Lyons won 20 games for the last time in 1930, going 22-15 with a 3.78 ERA, and leading the league with 29 complete games and 297 innings pitched. He also had two more outstanding seasons later in his career, finishing 14-6 with a 2.76 ERA in 1939, and going 14-6 with a 2.10 ERA in 1942. In addition to his three 20-win seasons, Lyons won at least 15 games three other times, and won 14 games three times as well. During his career, he led the league in wins, shutouts, complete games, and innings pitched twice each, and in ERA once.

However, in six seasons when he was a regular member of the starting rotation, Lyons lost more games than he won, twice losing as many as 20 games. In several other seasons, he was barely over .500, and in six seasons when he was a regular member of the rotation, his ERA was more than 4.00. He finished his career with an ERA of 3.67. On a superficial level, this figure hardly seems overwhelming. However, when one takes into account that most of his prime years were between 1925 and 1935, during a hitter’s era, 3.67 becomes much more impressive. Also, when one factors into the equation the poor teams he played for during his career, his sub-par won-lost records become much more tolerable.

Looking beyond just the sheer numbers, Lyons was an outstanding pitcher for nine seasons, and a good one in another two. Though he was not a dominant pitcher, he was arguably the best pitcher in the game in both 1925 and 1927, and among the top five in both 1926 and 1930. That might not be enough to make him a clear-cut choice for the Hall of Fame, but it should be sufficient to justify his 1955 selection by the BBWAA.

Hal Newhouser

Lefthander Hal Newhouser had a winning record in only seven of his 17 major league seasons, finishing at exactly .500 five other times. However, at his peak, he was the most dominant pitcher of his era, and he was clearly the best pitcher in baseball over a six-year stretch.

Although Newhouser struggled in his first five seasons with the Detroit Tigers, never finishing above the .500-mark, he came into his own in 1944. With most of the game’s top players serving in the military, Newhouser went on a three-year run comparable to any that the game has seen. In that first year, he finished 29-9 with a 2.22 ERA, 6 shutouts, 312 innings pitched, and 25 complete games. He was voted the American League’s Most Valuable Player that year and then again the following season, when he led A.L. pitchers in every major statistical category by compiling a record of 25-9, with an ERA of 1.81, 212 strikeouts, 313 innings pitched, 8 shutouts, and 29 complete games. In 1946, Newhouser fell just short of winning his third MVP Award, something that no pitcher in baseball history has done. That season, with most of the game’s greatest players back from the war, he finished runner-up in the voting to Ted Williams by finishing 26-9 with a league-leading 1.94 ERA, and totaling 275 strikeouts, 292 innings pitched, and 29 complete games.

Although Newhouser’s record fell to 17-17 in 1947, he was still a fine pitcher, compiling an ERA of 2.87, with 24 complete games and 285 innings pitched. He was the best pitcher in baseball once more in 1948, when he finished with a record of 21-12, an ERA of 3.01, and 19 complete games. Newhouser had two more good seasons in 1949 and 1950, winning 18 and 15 games, respectively, before arm problems prevented him from ever again being a dominant pitcher. However, prior to that, in the six seasons from 1944 to 1949, he compiled a record of 136- 67, won more than 20 games four times, led the league in wins four times, and won two MVP Awards. He ended his career with a won-lost record of 207-150 and an ERA of 3.06.

The sole argument against Newhouser would be that two of his greatest seasons occurred while most of the best players in baseball were away from the game. However, his great season of 1946 and his fine performances from 1947 to 1949 serve as proof that, at his peak, he was truly an outstanding pitcher. Therefore, his 1992 selection by the Veterans Committee should not be questioned.

Burleigh Grimes

During his 19-year major league career, spent almost entirely in the National League, Burleigh Grimes pitched for seven different teams. Most of his finest seasons were spent with the Brooklyn Dodgers and Pittsburgh Pirates during the 1920s, seasons in which he rivaled Dazzy Vance as the league’s best pitcher.

After two uneventful seasons with the Pirates in 1916 and 1917, Grimes was traded to the Dodgers, with whom he spent the next nine years. In his nine years in Brooklyn, Grimes won at least 17 games six times, surpassing the 20-victory mark on four separate occasions. He was particularly outstanding in 1920 and 1921, when he finished with won-lost records of 23-11 and 22-13, respectively, and ERAs of 2.22 and 2.83.

After compiling a record of 19-8 with the Giants in 1927, Grimes was traded back to the Pirates, with whom he had his finest season in 1928. That year, he finished 25-14 with an ERA of 2.99, and led the league with 28 complete games and 330 innings pitched. He finished third in the league MVP voting and was the best pitcher in the game for that one season. He followed that up with 17 wins in 1929, which was good enough to place him fourth in the MVP balloting.

In all, Grimes was a 20-game winner five times, won at least 16 games six other times, and finished with an ERA less than 3.00 four times. He led the league in wins twice, strikeouts once, innings pitched three times, and complete games four times. Grimes ended his career with a won-lost record of 270-212 and an ERA of 3.53—very respectable, considering the era in which he pitched. His selection by the Veterans Committee in 1964 would have to be considered a good one.

Red Ruffing/Lefty Gomez

Both Ruffing and Gomez were fine pitchers who were fortunate enough to play on Joe McCarthy’s great New York Yankees teams of the 1930s.

Red Ruffing is a perfect example of how playing on a good team can make a pitcher better. In six-plus seasons with the struggling Boston Red Sox from 1924 to 1930, he failed to win more than 10 games in any season, and was a two-time 20-game loser. His overall record with Boston and with the Chicago White Sox, with whom he ended his career in 1947, was a poor 42-101. In addition, only once in all those years did he finish with an ERA under 4.00 (3.89 in 1928). However, in his 15 seasons with the Yankees, Ruffing compiled an outstanding won-lost record of 231-124 and finished with an ERA under 4.00 thirteen times, three times compiling a mark under 3.00.

The thing that makes Ruffing so unusual is that, in his years with Boston and Chicago, his .293 winning percentage was below that of the rest of the team. Meanwhile, in his years with New York, Ruffing’s winning percentage of .650 was better than the overall mark posted by his team. From this, one could surmise that, when Ruffing was bad, he was really bad, and, when he was good, he was really good. One would also have to conclude that his success with the Yankees was not based solely on the fact that he pitched for a good team. Ruffing must have become a better pitcher once he came to New York because his winning percentage would not otherwise suddenly have become better than the rest of the team’s.

From 1930 to 1942, Ruffing failed to win at least 15 games only twice. He was a 20-game winner four times, won 19 games another season, and finished with 18 victories in yet another. His four best years were 1936-1939, during which time he was a 20-game winner each season, while compiling an overall record of 82-33. He also finished with an ERA under 3.00 in two of those seasons. He was among the five best pitchers in baseball during that period, and was arguably the top American League hurler in both 1937 and 1938.

During his career, Ruffing led the league in wins, strikeouts, shutouts, and complete games once each. He was selected to the American League All-Star team six times and finished in the top 10 in the MVP voting three times, making it into the top five twice. Ruffing ended his career with a won-lost record of 273-225 and an ERA of 3.80.

Ruffing’s teammate on the Yankees for 13 seasons was Lefty Gomez. Like Ruffing, Gomez benefited greatly from playing on some truly outstanding teams. However, unlike Ruffing, he spent virtually his entire career pitching for New York, making only one start for the Washington Senators in 1943. Therefore, his career winning percentage of .649 was considerably higher than Ruffing’s mark of .548, and ranks among the best ever.

In ten full seasons with the Yankees, Gomez was a 20-game winner four times, won at least 15 games three other times, and had only one losing season. Although he won 21 games in 1931, and another 24 the following year, his two best seasons were in 1934 and 1937, when he won the pitcher’s triple crown. In 1934, he finished 26-5, with a 2.33 ERA, 158 strikeouts, and 25 complete games. In 1937, he compiled a record of 21-11, with an ERA of 2.33, 194 strikeouts, and 25 complete games. Gomez was the American League’s best pitcher in each of those years, and among the top two or three in all of baseball (the N.L.’s Dizzy Dean and Carl Hubbell were the number one hurlers in 1934 and 1937, respectively). He was also among the top five pitchers in the game in 1931, 1934, and 1938.

Gomez led American League pitchers in wins and ERA twice each, strikeouts and shutouts three times each, and complete games and innings pitched once each. He was selected to the All-Star Team seven times, and he finished in the top 10 in the MVP voting three times, making it into the top five twice. He was a very good pitcher. But was he any more deserving of Hall of Fame honors than two of his contemporaries, Wes Ferrell and Lon Warneke?

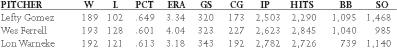

Let’s take a look at the career numbers of all three pitchers:

Both Ferrell and Warneke were actually quite comparable to Gomez. Although both men pitched for lesser teams throughout most of their careers—Ferrell for the Indians and Red Sox, and Warneke for the Cubs and Cardinals—they finished with outstanding winning percentages, and compared favorably to Gomez in most other categories. Gomez was more of a strikeout pitcher, but both Ferrell and Warneke had better control. Gomez’s earned run average was considerably lower than Ferrell’s, but the discrepancy could be attributed largely to the fact that the former was a lefthander pitching all his home games in spacious Yankee Stadium, while Ferrell pitched in smaller ballparks. Also, Ferrell’s last five seasons were poor ones in which his ERA never fell below 4.66.

From 1929 to 1932, then again in 1935 and 1936, Ferrell was one of the two or three best pitchers in the American League, winning at least 20 games in each of those seasons, and surpassing 25 victories on two separate occasions. With the Indians in 1930, he finished 25-13 with an ERA of 3.31 and 25 complete games. With Boston in 1935, he compiled a record of 25-14 with a 3.52 ERA and 31 complete games. Ferrell led the league in wins once, complete games four times, and innings pitched three times, and was one of the greatest hitting pitchers in baseball history. He finished in the top 10 in the MVP voting twice, making it into the top five once.