Batista Unleashed (8 page)

Authors: Dave Batista

Finally, when we were completely exhausted but somehow still alive, he came up to us.

“Forget it,” he told us. “You guys are out of here. You’re done. You’ll never be professional wrestlers. You guys don’t have the fucking heart. Get out of my class.”

So we left.

HEARTBROKEN

It makes you think.

I had this guy who never amounted to anything tell me I would never be a professional wrestler, that I didn’t have what it takes. And a few years later, I was headlining

WrestleMania.

What does that tell you?

I wonder how much talent he chased out of there. The goddamn WCW went under not too much longer after that. Maybe there’s a connection.

In my opinion, Lance had a lot more potential than I ever had. Except for his nose. But Sarge and the experience at the Power Plant stifled Lance’s wrestling ambitions for a long time. He still has a dream, believe it or not, of being a pro wrestler, but he hasn’t made it yet.

Hey, Sarge, if you’re reading this—I think about you every day, you fuckin’ piece of shit.

Yeah. You’re a fuckin’ piece of shit.

On the one hand, though, maybe Sarge did help me, because he pissed me off enough to say, “Fuck, I’m going to make it.”

On the other hand, that sure wasn’t what he was trying to do. He was trying to humiliate us, and he pretty well did that.

On that day, when I went home, I wasn’t feeling like I was going to show him up or prove I could make it in WCW’s rival or any other wrestling franchise. All I was really feeling was heartbroken.

Photo 3

SOMEWHERE IN ILLINOIS

More nights than not, I’m the last one out of the locker room. Which is a pain for the security guys, because they can’t move on until I’m out of the building.

They’re patient tonight. By the time I’m done, the truck has already been packed and is heading up toward Urbana, Illinois, and tomorrow’s show. It’s past midnight; they have a couple of hours of driving ahead of them.

So do I.

It’s started to snow and the Lincoln is covered with a light frost. I brush it off and get into the car. I’m real lucky tonight—not only did a friend of mine start it up for me so it’s nice and warm when I get in, but none of the boys played with the seat or the radio. A lot of nights I get into the car and my knees are slammed against the steering wheel and country music is blasting in my ears.

I like all kinds of music, but not that. Not at one in the morning.

Or is it two?

The GPS system gives me directions and I head out of the parking lot toward the highway. Sixty seconds later, I’m stuck in a back alley behind a utility building, squeezed tight against a fence and a stack of cement blocks.

I can see the highway, at least. I back out, fishtail around and ignore the one-way signs, and finally find the road.

Most weeks, our shows are at night, and I can sleep late the next day. But tomorrow is Super Bowl Sunday. To make it easy for people to see the game after our show, we’re starting early, at one o’clock in the afternoon. Because of that, I had to change around my hotel reservations. I know from experience it will be best to get up to Urbana first and then sleep; the hotel is only a mile or so from the arena, and even if I get to bed late it’ll be easier to get up in the morning and get there on time. But it means driving when I’m exhausted, at the end of a long day.

I break the long, post-midnight run from Carbondale with a stop at a Denny’s somewhere in the dark Illinois countryside. A young waitress who says she’s just working the midnight shift to bring home a little extra money for her family shows me to a table in the back. She looks at me kind of funny as she hands over the menu.

“Anyone ever tell you that you look like Batista?” she asks, ducking her head a little bit as if she’s trying to poke her eyes under the brim of the cap I’ve pulled low over my face.

“Man, I am so tired of hearing that,” I say. Partly that’s a joke, and partly that’s a plea to get away unrecognized.

She seems to think I’m serious and goes away. Truth is, with my cap and street clothes and heavy winter coat, I don’t really look like the World Heavyweight Champion who was strutting into the ring just a few hours ago—at least I don’t think I do.

But the fans know. It’s dumbfounding—and humbling—but they sure do know. It turns out that the waitress really did know but was trying to be polite.

The restaurant manager comes over with my iced tea a short while later. “We do know who you are,” she tells me. “But we want to respect your privacy.”

Fair enough. I appreciate that.

While I’m waiting for my food, I try to call home to see how my daughter did on a test she was going to take today. I have some other calls I’m supposed to return, too, and even though it’s ridiculously late I take a stab at it. But one by one people start losing their shyness and come over to see me. There’s a little girl who’s crying she’s so excited about getting an autograph, and then a waiter comes to talk about how his little brother would really be amazed to get an autograph.

Once you’ve been on TV, people want your autograph. Some fans are really cool about it, waiting until I’m done eating or whatever and asking very politely. Others, a few, can get pretty obnoxious. A few think that the price of a ticket or just turning on the TV entitles them to every part of your personal life. And since you’ve given up your personal life, they can have an autograph any time they want it, even if you’re on the phone or eating—or trying to do both at the same time.

Those are the extremist fans, though. Not everybody’s like that. A lot of people are really pretty polite. And some are so nervous, they don’t even realize they’re being rude.

Tonight, I end up posing for photos with the whole staff. They’re so jittery they have trouble with the camera, and it’s quite a while before I’m back on the road.

When you’re tired and hungry, the attention can be a bit of a strain. But the truth is, I am grateful for my career and I understand what the fans are looking for. They want to connect with the good guy, have a hero in their lives who struggles against all the bad shit that happens to them in this world—a crappy day at the office, tough times at home. It’s all stuff I went through, and still do.

Outside, the snow has stopped. I gas up the car at an all-night gas station nearby and get back on the road…

DUES

In 1999, I turned thirty years old.

In a lot of professions, that’s nothing. If you’re a CPA, a lawyer, a teacher, a businessman, you’re really just getting started at thirty. You can look forward to another thirty-five or forty, maybe even fifty years in your career.

But in wrestling, thirty is damn old. And it’s one thing if you’re thirty and you’re in the prime of your career. If you’re thirty and you haven’t hit the big time, it’s pretty ridiculous to think that you’re going to go anywhere. A lot of wrestlers have to hang up their gear by the time they reach their midthirties. Their bodies just won’t do what needs to be done.

A guy like Ric Flair is an obvious exception—he just keeps going and going—but even Ric was a champion at age thirty.

Me?

I wasn’t even in the ring yet.

CRUSHED

I really had my heart set on wrestling. Despite my fiasco at the Power Plant and Sarge’s bullshit pronouncement that I didn’t have what it takes to be a wrestler, I wanted it in the worst way.

Most bodybuilders think to themselves that they can become a pro wrestler, but most who try to do it find out it’s a lot harder than they think. Instead of trying to change their way of life to make it, they give up.

I didn’t do that. I pursued it with everything I had. It was really out of passion and desperation.

I say desperation because I really was desperate. I didn’t know, I didn’t want, to do anything else. It was all or nothing.

It had taken me forever to figure out what I wanted in life. I’d drifted into bouncing and working in gyms, not really with much of a plan. It was good work and I liked it. I even got paid pretty well at times. But when I started taking an interest in wrestling, it was different. There was a real passion there.

I’m not going to compare it to love. Love is a different thing, something between people. You know that and I know that. But I really felt a deep desire to make wrestling my life. I started watching the shows a lot and thinking of myself as a wrestler, figuring out what I would do. I was really into it. Every other possibility in life suddenly closed off. That was what I wanted.

Being told that I didn’t have what it took, that I would never be a wrestler, crushed me.

For two or three days. Then I started making phone calls.

“YOU SERIOUS, SON?”

One of my calls was to World Wrestling Federation. I was just a voice over the phone to them, but whoever answered initially passed me along to someone. I don’t remember who, but I do remember what he said:

You serious, son?

I said I sure was. He recommended that I go to wrestling school first to learn the basics, and told me about the Wild Samoan Training Center in Allentown, Pennsylvania. He may also have mentioned that I could talk to Jim Cornette, who was helping spot young talent, the next time WWE came to town.

It just so happened that World Wrestling Federation was coming into town for a house show at the MCI Center in D.C. right around that time. So I went down there and went up to someone and asked if I could speak to Jim Cornette.

I’ll take a little time out here to mention Jim Cornette’s background. A lot of his two decades or so in the business has been spent helping develop new talent and getting guys ready for WWE. He’s also done booking and on-camera work, been a promoter, and most recently was with TNA Wrestling. Some fans might remember that he started Smoky Mountain Wrestling in the early nineties. By the time I heard about him, he was with the company, helping develop new faces. I ended up training under him a year later or so at Ohio Valley Wrestling, or OVW.

So anyway, I went down to the arena beforehand and just walked in. Nobody ever said anything to me. I was there for a little bit. One of the promoters at the time, Doug Sharfsburg, came up to me and asked me what I was doing.

“I’m looking for Jim Cornette,” I told him. “I was told I could meet him here.”

“What do you need him for?”

“I was trying to get a job, and—”

“Security!”

Doug called security on me, and before I could get much of an explanation out of my mouth, I was thrown out of the building.

Nobody was going to make this easy for me.

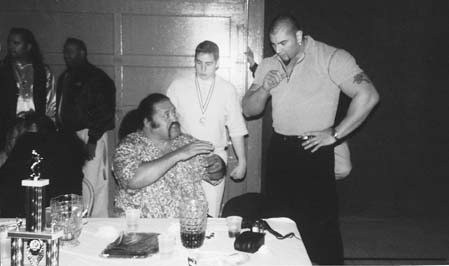

Photo 16

That’s me with Afa.

AFA

Doug was just doing his job. A couple of years after that, when I was with WWE, we were doing a house show at MCI and I ran into him. I reminded him of that night.

“Oh my God, was that you?” he said.

He felt so bad that from that day on, whatever I asked Doug for, tickets, whatever, he’s given me. He’s probably apologized a hundred times. But he thought I was just some guy who wasn’t supposed to be back there. And at the time, I guess I wasn’t.

Where I did belong was in wrestling school, the Wild Samoan Training Center, to be exact. Taking lessons from the Wild Samoan himself, Afa Anoa’i.

Afa is a legend in the pro wrestling world, but not too many people know that he joined the U.S. Marines when he was only seventeen. This was during the Vietnam era, when most people thought joining the military wasn’t really the coolest or smartest thing you could do. He came out of the service and began wrestling during the 1970s.

He was pretty successful, but it wasn’t until after he taught his brother Sika to wrestle that he really catapulted to fame. In the 1980s, Afa and Sika formed the Wild Samoans tag team. I’m not sure how many championships they won altogether, but I know they had the World Wrestling Federation titles at least three times.

Since he’s retired, Afa has become pretty well known in the industry as a trainer. There’s a whole flock of Samoans related to Afa who found their way into the sport because of him. Just in his family, there’s an all-star cast of guys he’s helped: Samu (his son), Rikishi and Yokozuna (his nephews), and Umaga.

Afa’s school is located in Allentown, Pennsylvania. There’s a lot of wrestling history in that area; Vince McMahon’s father used to do television tapings there before World Wrestling Federation expanded into a national franchise. It’s not so far from New York and other big cities that you can’t get there in a few hours, but it’s far enough off the beaten track that a young guy can learn the trade without being completely distracted.

MY FRIENDS WERE THERE FOR ME

Like any other school, the Wild Samoan Training Center charges tuition. Not only did I have to come up with that, but I needed money to live on. Angie was working, but she wasn’t making all that much money and there was no chance of her supporting both of us.

So I talked to my friends Jonathan Meisner and Richard Salas. Both Jonathan and Richard have been my friends for a long time; even today, they’re still two of my very closest friends. I’ve known Richard since high school, when he and I and his brother Wilbur—another close friend—wrestled together. He’s Filipino and we had a little clique going back then. I still kid him because he hooked me up with my first wife—though believe me, I don’t hold it against him. I met Jonathan a few years later through Richard, and we’ve been incredibly close for years and years. He still helps me out. I can’t even tell you how much he helps me out. He’s my closest friend in the world.

When I went to them and told them what I wanted to do, they put their money where their friendship was. They bankrolled everything for me. It was probably around $150,000 altogether. They never ever once said no; they never even asked when they were going to get the money back. All they said was, “We know you can make it.”

Really, they made my dream possible for me. They bankrolled the whole thing. They just did it on friendship. Those are friends. Real friends. I love them both very much.

WHERE HAVE YOU BEEN?

We all went up to Pennsylvania together, my wife, Angie, and Jonathan and Richard, to check out the school.

Afa was there. I recognized him immediately.

And in a way, he recognized me. He came up to me and said, “Where’ve you been?”

It was like I was the student he’d been looking for his entire life. He treated me like a son right off. Afa, he’s a big guy. He’s from a family of big guys. But there were no big guys for him to train there. Until I came. I was kind of like his pet project—his little toy.

To this day, I think of Afa as a member of my family. I call him Pops. Anytime Pops calls me up to do an appearance, if my schedule permits, I make it my business to help him out. I’ve helped him raise money for his charity organization. It’s a debt I owe to him as a wrestler, and also as a person. He’s really been that good to me. I love him for that.

ALLENTOWN

We moved to Allentown, close to Afa. We packed our stuff in a tiny car—my wife owned a Honda Del Sol. I don’t know if you remember the Honda Del Sol, but it was a very small sports car, smaller than today’s Civic. You should have seen me in a Honda Del Sol. It was ridiculous.

Anyway, we moved up to Allentown. The training center was in Hazelton, Pennsylvania, which is about forty-five minutes away. For a while, Angie was traveling back to Virginia to work, because it was so hard to find a job up there. We lived in the nicest apartment complex around, but just outside of where we lived, there were a lot of real rundown buildings.

I don’t know about now, but at the time unemployment was real bad. Allentown was part of the “rust belt.” America’s industrial heartland had basically rusted by the late 1990s, as old industries suddenly found they couldn’t compete. A lot of jobs were lost when manufacturing started going overseas. Unemployment surged. Whole cities and regions were suddenly poor. You had a lot of social problems; still do.

That pretty much described Allentown when I was there. There wasn’t a lot of work, and seeing young teenage girls pushing strollers around was not uncommon.

I actually didn’t train with the class much when I was at the school. I was Afa’s own little pet project. He and his son worked with me a lot, personally, just one-on-one. Simple things. I learned how to run the ropes, how to take falls. Very, very basic stuff, but I had to learn it all.

There was a gym in town called Phoenix Fitness. I couldn’t really afford a gym membership, but one day I went in and, hoping for a cheap rate, introduced myself and told them that I was trying to become a pro wrestler. They actually gave me a free membership for myself and Angie. They felt that I was going to make it as a professional wrestler. I’ll never forget their kindness.

I’d never done much cardio work during my weight-lifting years. I started doing it in the ring, trying to get in better shape. That’s one reason that throughout those early years I consistently dropped weight. You can look back at the pictures and see me getting progressively leaner.

I did a few matches while I was at the school, but they weren’t really matches. I’d go out there and hit the guy with a couple of things and kind of kill him. It’d take about thirty seconds and the match was over; I was out of there. I still had a lot to learn.

THIS GODDAMN ARM

I also had my first injury while I was training with Afa. It was a torn triceps, the same one that’s given me problems in WWE. I believe it must go back to a really early injury when I was lifting weights that were way too heavy. At the time, I didn’t notice any real problem, but I may have been setting myself up for problems later on. It was one of those things that you don’t realize at the time because you’re young, full of piss and vinegar. As you start to get older, the stuff starts catching up with you.

Anyway, I was in the ring and I was doing front bump drills: you jump up in the air and land on your stomach. My arm had been bothering me, God, for a couple of years, to the point where I couldn’t do bench presses anymore, or even push-ups. I never really knew what was wrong with it, but it hurt like hell if I pushed it.

That day it just snapped. It hurt like hell—and then some. I went to the hospital, and they said, “Oh you just pulled a muscle.”

“I don’t think so,” I said. “It’s swelled up twice as big as normal. I don’t think that’s a swelled muscle.”

“Oh, yeah,” said one of the doctors. “Just take some Advil and you’ll be fine.”

Uh-huh.

That same night, my arm swelled up some more. The pain was so bad I had to go to the emergency room. They had MRIs done and we found out it was torn. I had to have surgery to reattach it.