Behind Closed Doors (30 page)

Read Behind Closed Doors Online

Authors: Elizabeth Haynes

Caro nodded. ‘Clive was friends with Annie’s parents. He was a schoolteacher, and Annie’s father was the headmaster at the school where he worked. They married as soon as Annie turned sixteen, with the consent of her parents. They didn’t have the girls straight away, though. I think they were married ten or eleven years before Scarlett came along.’

Sam fell silent, considering.

‘And before you ask,’ Caro continued, ‘yes, we did look at Clive’s relationship with his daughters. But Juliette wasn’t saying anything much, and there were no concerns at Scarlett’s school. Social Services had had no contact with the family, either.’

Sam said, ‘I didn’t realise he was a teacher.’

‘He wasn’t when Scarlett went missing. He gave up teaching when they got married, worked as a manager in an electronics business. Retired from that a few years ago.’

When Sam got back to her own car a few minutes later, a wave of something so despairing came over her suddenly that she had to sit still, taking deep breaths, unable to drive until it passed. There were some houses you went in as a police officer that made you want to go straight home and get in the shower, put your clothes in the wash and scrub your shoes. The Rainsford house hadn’t been like that, it was clean and tidy, but there was something so hideous about it that Sam felt overwhelmed.

Driving through the town centre, she took a detour past the bus station, and then up to the railway station for good measure, looking at all the kids wearing hoodies, looking for a khaki coat, looking for Scarlett’s shape and posture, but there was no sign.

– Sunday 3 November 2013, 14:20

Les Finnegan was loitering in the doorway to Lou’s office. Tempting as it was to tell him to sit down, he’d just been outside for a fag and it was a small room. Lou had been out to the supermarket to find some lunch and the carrier bag was calling her from below the desk.

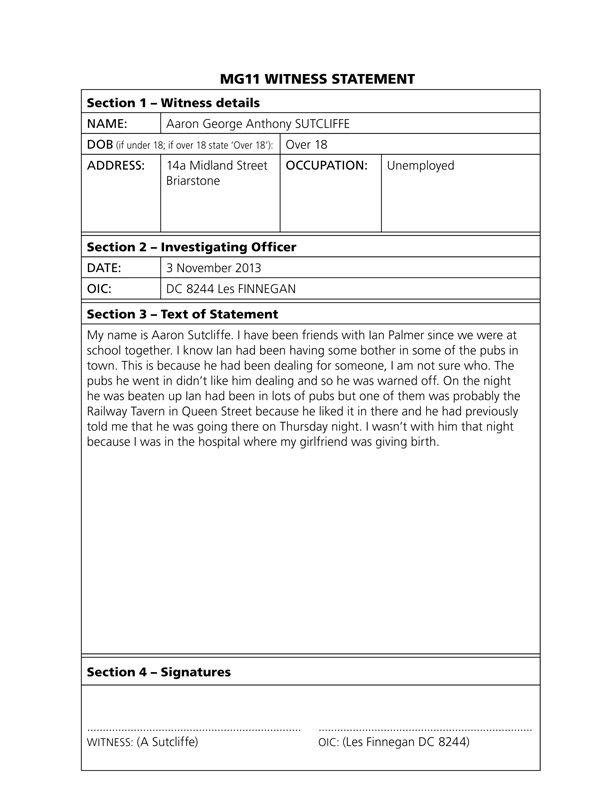

‘So tell me about Sutcliffe.’

‘He ended up not being charged for the assault, so I got him to agree to be interviewed about Palmer before he disappeared. He was basically just mouthing off, half a ton of crap with a little diamond or two buried in there if you know what you’re looking for. Apparently Palmer had been dealing in the Railway Tavern a while back.’

‘McVey liked to keep drugs out of his establishments,’ Lou said. ‘Made him feel like a fine upstanding citizen, or something.’

‘Sutcliffe seems to think Palmer might have been dealing for Darren Cunningham. Or Mitchell Roberts. Or he actually doesn’t know and is trying to pretend he’s smarter than he is.’

‘That’s not in his statement,’ Lou said, reading it on the screen.

‘No, well, when I was taking his statement, funnily enough, he was a bit less keen to sign his name to that bit.’

While Les was talking, Lou could see over his shoulder into the main office where Sam had just come in.

‘I think the dealing link is the way forward,’ she said. ‘Can we try to narrow it down? Maybe Palmer tried to short-change one of them. Didn’t I read something about one of Cunningham’s shipments going wrong? Perhaps Palmer decided to keep some of the stash. We don’t have much at the moment; we might as well work through possible motives.’

Sam appeared behind Les. ‘Afternoon, ma’am, sorry to interrupt…’

‘That’s okay, Sam. I need you, in any case. Les, can you see what you can find on the intel?’

Les nodded and went back in the main office, squeezing unnecessarily close to Sam on the way past.

‘Shut the door,’ Lou said, ‘and have a seat. How’s your morning been? How was Clive Rainsford?’

‘I can’t tell you how much that house gave me the creeps,’ Sam said.

Now that Les was gone, Lou began to dig into her egg salad. It was so cold from the supermarket’s chiller cabinet, it made her teeth ache. There hadn’t been much left to choose from.

‘I haven’t had a chance to look at the updates,’ said Sam. ‘What else has come in on that burglary?’

‘They’ve got the property list,’ Lou said. ‘Interesting mix of small, portable things and then the car. And food, too – specifically bread and a bag of apples, both of which were in a carrier on the kitchen table. You’re thinking it was Scarlett?’

‘I don’t know. It’s just worth considering, I guess.’

Lou was crunching on grated carrot. ‘Just too many slightly odd things,’ she said. ‘But, as you said, we don’t know if she can drive, do we?’

Sam shook her head. ‘I feel awful about the whole thing. I wish we could have got her somewhere decent to stay. She just deserves a chance, and it feels like I let her down.’

‘Sam, you did your best. And she’s not fifteen any more – she’s an adult. But I agree it’s a bloody nightmare.’

‘I’m not surprised she doesn’t want to go home, having met Clive.’

‘From my conversation with Annie yesterday, it feels to me as if she’s not allowed to have her own opinions about anything. Clive’s completely in control.’

‘He was giving a good old show of losing it this morning,’ Sam said.

‘But you didn’t buy it?’

Sam shrugged.

Lou threw the plastic container containing the last few watery bits of salad into the bin. Her stomach was still rumbling but that would have to do – and she had so much else to catch up on, it was quite possible she’d have to miss dinner too. Coffee and KitKats would keep her going till then.

‘So,’ Lou said, ‘this afternoon. Anything you’re already committed to?’

‘I need to write things up, then I was going to go have a look for Scarlett.’

‘Can you do something else for me? Les had a chat with Aaron Sutcliffe this morning – he’s a friend of Ian Palmer’s. Seemed to think Palmer might have been dealing for Darren Cunningham. It’s not much of a link, but we don’t have anything else. Les is looking it up now to see if there’s something to go on, but can you task him or someone else to follow it up?’

– Wednesday 24 October 2012, 09:15

It was only when Scarlett was sitting at the back of a McDonald’s, with a coffee and a breakfast muffin, that she remembered the money she had hidden inside her bra. The woman had given her money and she hadn’t needed it. Scarlett felt a pang of guilt at this, and resolved to pass on the karma somehow. It wasn’t her money to keep. She should give it to someone else who needed it more than she did.

The coat was warm, like a duvet around her. She loved it fervently, passionately already, because she had been given it by someone who cared. And it was hers; it was her lovely warm coat. It was the only thing she owned.

More than that, it had afforded her an unexpected level of protection: turned her from a half-dressed, shivering, terrified-looking girl into someone respectable and therefore invisible. She could do with a pair of jeans and some proper shoes, too – but the coat was a great start.

She had one eye on the door, in case the men should come in, looking for her. But there was something comforting about the bright, cold daylight outside, the sudden bursts of sunshine; the strangeness of being around people in a public place without someone watching her; the fact that, once she’d sat down, she had become suddenly, unexpectedly normal, which meant nobody seemed to be paying her any attention at all.

This was what real life looked like. There were families in here, kids, teenagers chatting and laughing. All sorts of people walking past outside, going about their business as if nothing was wrong.

Yet, a few miles away, a warehouse in a desolate industrial estate was being used to film young women being tortured, being shot. Women who had been through unimaginable hell already; women who had been bought and sold like a commodity and, having reached the end of their usefulness, were being given one last job to do before they were discarded. The coldness of the whole process and the fact that she had escaped from this fate made Scarlett feel detached. She wanted to go up to people, shake them, say,

Do you not know what’s going on, right under your noses?

But who would listen? Who would believe her?

She needed to form some sort of plan, something to focus on. She couldn’t sit here all day; she would start to attract attention. She needed to keep moving, and in order to do that safely she needed a plan. The coffee was helping, the daylight was helping, but inside her the adrenalin was starting to metabolise out of her system and the exhaustion of having been awake for more than twenty-four hours was beginning to overwhelm her.

Focus, Scarlett.

She needed to get far away from here, that much was certain. She didn’t want go to the police. There was nobody she trusted – she was on her own – but this wasn’t entirely a bad thing. On her own she had survived so far, and she had escaped. There was a triumph in that, at least.

She needed to get away from here, then. Once she was out of the town she would find somewhere safe to sleep tonight. This would mean spending some of the money she had, and it would not last long. How could she get more, without drawing attention to herself?

In the pocket of her new coat was a handful of coins. Across the road, in the shelter of an office block, Scarlett could see two green public telephones. They were fixed to the wall of the building, under a concrete overhang which provided shelter for the smokers and the coatless.

She had been away for years. Would Juliette even remember her? Would they even still be living in the same place? What if

he

answered the phone?

Scarlett got out of her seat and left the restaurant, staying close to the building, looking up and down the street in case she saw someone she recognised. Then she crossed the road quickly, to the payphones. One of them just accepted cards, but the one on the right had a slot for coins. The instructions were in English and Dutch. The first time she tried, she forgot to add the international dialling code. The second time, there was a pause, and then the sound of the phone ringing on the other end.

– Sunday 3 November 2013, 15:50

Les Finnegan and Jane Phelps eventually found Darren Cunningham enjoying a smoke outside his office: one of them, anyway, since he had several. The establishment he was frequenting today was also known as YouBet, or David Henderson Bookmakers and Turf Accountants Limited, one of Briarstone’s few independent bookies and Cunningham’s particular favourite.

Les parked the job Peugeot in a space outside the chip shop, two doors down from the betting shop in Turnswood Parade. ‘There he is,’ he said, nodding towards a little group of individuals who were hanging around outside.

There were two lads straddling BMXs, a bloke sitting on the bench and a lad sitting on the railing separating the pedestrian walkway from the car park, which was a good four feet lower, swinging his legs. It would be worth it to watch in case he fell off. All four of them were wearing Sports Direct’s autumn/winter collection, a mishmash of nylon and sweat fabric, greys and navy-blues and blacks, baseball caps worn the wrong way round.

Both officers paused before getting out. It was just possible – you never knew – that some deal was about to go down, which would give them a couple of arrests and a nice little bit of disruption to cheer everyone up. Cunningham didn’t deal on the streets, though; he was way beyond that now, even if he did still live at home with his mum.

The two lads on bikes were moving on. There were some elaborate handshakes, and, by the time Les and Jane approached, the bikes were weaving alarmingly between the pensioners making their way from the bus stop to Iceland. One of the lads passed, turned back and shouted, ‘Daz!’ over his shoulder, alerting Cunningham to the approaching officers of the law. Oh, well. It wasn’t as if they were going for stealth.

The lad on the railing, a long, thin streak of drool with skinny white ankles sticking out of his trainers – no socks; there was something deeply offensive about the lack of socks, in November – jumped to his feet when he clocked them.

‘Don’t want to interrupt,’ Jane said cheerfully.

‘I’m just off,’ said the thin lad. Dark hair, full of gel or grease or something.

‘Stay where you are, mate,’ Cunningham told him.

Obligingly he clambered back up to the railing, snagging the back of his nylon trackie bottoms on the metal and treating Jane to the sight of a hairy white crack above the words ‘Calvin Klein’.

‘Mr Cunningham,’ Les said, leaning casually against the railing. ‘DC Les Finnegan; this is my colleague, DC Jane Phelps.’

‘I know,’ Cunningham said.

Jane remained standing next to the bench. It wasn’t often she had a height advantage and she wasn’t about to waste it by sitting down. To the charmer on the railing she said, ‘I don’t think we’ve had the pleasure. What’s your name?’

The lad looked to Cunningham as if asking permission to speak. ‘Jonny.’

‘Jonny…?’

‘Parkinson.’

‘Look,’ Cunningham said, ‘we’re not doing nothing. What’s the problem?’

Les turned his attention back to Cunningham. ‘No problem, Darren. Just wanted to have a little chat, see how you are.’

Cunningham snorted. ‘Yeah, right.’

‘Sorry to hear about what happened to Ian,’ Jane said.

‘Who?’

‘Ian Palmer. One of your mates, isn’t he?’

‘No,’ Cunningham said. ‘Don’t ring a bell. You know him, Jonny?’

‘No.’

‘Oh? We heard he was working for you – doing the odd bit here and there. And there’s no point pretending you don’t know him, Darren; you’ve been stopchecked in his company before.’

‘What happened to him, then?’ Cunningham asked. He scratched his half-arsed beard with bitten grubby nails.

Jane couldn’t help thinking that he didn’t look like Eden’s current drug overlord, but then she caught sight of the shiny watch, heavy, under his hoodie sleeve. And when your mum did your washing and cooked you pizza and potato waffles for your tea, what were you going to spend your money on? She was willing to bet his bedroom looked as if he’d won

The Gadget Show

’s tech giveaway. He was older than he looked, too – late thirties, but not exactly a magnet for the ladies, despite the wealth. These days his mum was driving around in a 2013-reg BMW, Darren himself not actually able to get behind the wheel thanks to a twelve-month ban. If he had that much money kicking about, no wonder he was spending his afternoons laundering it in YouBet.

‘He got his head kicked in,’ Les continued. ‘Still in hospital. We thought you might have paid him a visit, poor lad.’

‘Look, we ain’t mates. Just ’cause I’ve been seen with him once or twice.’

‘He knows you, all right,’ said Les. ‘Knows you very well. And all about your business.’

Well, that did the trick. Cunningham’s eyes narrowed and he sat up a little straighter.

‘What’s that supposed to mean?’

Jane said, ‘We just wanted to ask if you’d got anything to share with us about what happened to him. His poor mum’s beside herself, you know. And I’m sure it would help you out to get whoever assaulted him put away, wouldn’t it?’

Jonny Parkinson wobbled slightly on his perch.

Cunningham scuffed at the dirty tarmac with the toe of his trainer. ‘Got nothing to tell you.’

Jane gave Les a look.

‘If you change your mind,’ Les said, offering a card, ‘give us a call, right?’

Darren Cunningham glanced at the proffered card, looked pointedly away.

Les pocketed it again. ‘You can always get hold of us, anyway. Dial 101. Might be trickier to get through that way, but I’m sure you can remember the number, can’t you? Just a word to the wise, Mr Cunningham. Be careful who you trust – know what I’m saying? Gets a bit difficult to tell your enemies from your friends, after a while, especially in your line of work, where allegiances change all the time.’