Belisarius: The Last Roman General (12 page)

Read Belisarius: The Last Roman General Online

Authors: Ian Hughes

A large proportion of the infantry force which may have been classed as part of the

paighan,

but which were highly regarded by the Sasanids, were the foot archers. They were armed with the traditional composite bow and, when possible, with a large shield. In attack they were used to disrupt enemy formations prior to the

savaran’s

assault; in defence they were to disrupt, or even halt, enemy attacks.

Allies and Mercenaries

Alongside the native troops were the allies and mercenaries who were used to supplement the army. The Armenians supplied both cavalry and infantry to the Sasanid army and were highly regarded by them. The elite Armenian cavalry were trained and equipped as the

savaran

and were considered their equal. The remainder of the cavalry joined the light horse archers. The Armenian infantry, armed with spear and sling, were also well respected by the Sasanids and boosted the overall quality of the infantry forces available.

Finally, there were the troops supplied by, for example, the Lakhmids, Alans, Kushans, Saka and Hepthalites. Mainly composed of light horse armed with bows and/or javelins, when combined with the Sasanid light horse archers they made formidable opponents.

Although most allies provided light horse troops, the exception was the Lakhmids. An Arab tribe, the Lakhmids were very highly rated, and, like the Armenians, their cavalry was trained and equipped to fight alongside the

savaran.

They were a major ally, assisting the Sasanids in their wars with the Byzantines and helping to neutralise the threat of the Ghassanids, an Arab tribe allied to the Byzantines.

Elephants

One major difference between the Byzantines and the Sasanids was the latter’s use of the war elephant. Imported from India, the elephant was guided by a trained mahout, who sat astride its neck, and a turret-like howdah carrying two or three warriors armed with bows or javelins strapped to its back. The elephant had three functions. One was to provide a missile platform, allowing the archers in the howdah to rain arrows on the enemy from a higher vantage point affording greater vision to the archers and partly negating the enemy’s use of shields for protection. The second was to cause fear and consternation to the enemy. Much has been made of the fear the elephant inspires in horses unused to their presence, yet the sight of such a large creature bearing down would also have been terrifying for enemy foot soldiers. Third, the elephant was capable of smashing into enemy troops and causing widespread death and chaos, which could then be exploited by supporting troops. In order to help the process, it was common to give the elephants alcohol prior to battle. This would aid in making the elephant aggressive, helping to override the serene instincts of an otherwise relatively peaceful creature. In theory, and many times in practice, the elephant could be a battle-winning weapon.

Unfortunately, the theory did not always work in the field. Elephants, like most animals, do not like the noise, confusion and pain found on battlefields, and were therefore liable to become uncontrollable – on more than one occasion turning away from the enemy and running back through their own troops, killing and disordering them as they went.

The double-edged nature of the elephant resulted in it always being a risky weapon to use, and it is noticeable that the Byzantines – ever willing to adopt successful enemy weapons – did not maintain any war elephants for their own use, except in the games. They were rarely used in the wars against the Byzantines.

Organization

In the main, it would appear that the Sasanids organised their own troops – at least their cavalry, if not necessarily their infantry or the allied troops – using a decimal system, although it must be admitted that the evidence is sparse. The smallest unit mentioned was the

vasht.

Although no figure is given for the size of this formation, earlier practice would suggest a strength of approximately 100 men. A larger unit was the

drafsh,

which appears to have numbered around 1,000 men. Finally, the largest division was the

gund,

probably of about 10,000 men.

Although based mainly upon deduction and previous practice, support is given to the theory by the fact that armies were usually stated to have had around 10,000 men, led by a

gund-salar

(general). If we allow for a personal bodyguard of up to 2,000 men, the general might have a total of around 12,000 troops. However, in the field the numbers would have varied due to disease/ illness, injury or any of the other factors that could reduce unit rosters. Also, it should be borne in mind that historians such as Procopius tended to give round figures, meaning that anywhere between around 8,000 to around 12,000 may have been rounded to 10,000, therefore this hypothesis should be treated with caution.

Leadership

A full muster of the standing army, or

spah,

could be led by the king or, more rarely, by his deputy, the

vuzurg-framandar

(great commander). In the main, however, the command of the army usually fell to the

eran-spahbad,

who was usually a member of one of the seven top families. If he was unavailable to lead an army, or the army was simply a small defensive force, command could devolve upon the

spahbad

or the

marzban.

These both combined the roles of general and local governor, though only the

spahbad

appears to have been given the power to conduct formal negotiations.

The total strength of the Sasanid army in the late sixth century has been estimated at approximately 70,000 troops. If this is accurate, then there may have been four

gund,

each of around 12,000 men, with a seperate field army of approximately 22,000 men – including the 10,000

Zhayedan,

the 1,000

pushtighban,

the

gyan-avspar

and other guard units – being called to muster in Ctesiphon, under the command of the king, should the need arise.

Defensive Equipment

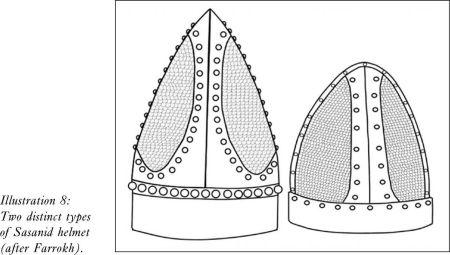

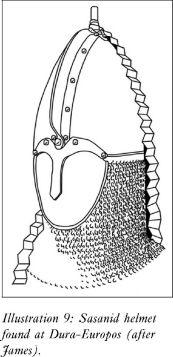

Helmets

Helmets were similar in form to those worn by the Byzantines, both having derived from the same Iranian and steppe originals. They included ridge helmets and spangenhelms, with the addition of chain mail hanging from the rims of the helmets as further protection to the head, neck and face. The main stylistic difference was that in the

bashlyk

type of spangenhelm, the bowl formed a higher peak than in the Byzantine variants, possibly to aid in the deflection of vertical blows to the head.

Like Byzantine helmets, all of these could be overlaid with gold and/or silver or be tinned, and have semi-precious stones attached to improve appearance.

Armour

Again, the armour worn was similar – if not identical – in style to the types worn by the Byzantines. This included lamellar, scale and chain mail armour. However, unlike the Byzantines, it appears that the Sasanids commonly combined the various types into one piece of armour, designed to utilise the best properties of each type to cover the most appropriate area of the body. As a consequence, a

savaran

horseman may have worn chain mail overlaid with lamellar armour to give extra protection to the torso, coupled with laminated defences for the arms and legs. He may also have worn a

bazpan

(armoured glove) to protect one or both hands.

However, probably due to the cost and complexity of manufacturing such complex armour, plain mail seems to have been slowly becoming the norm for the Sasanid army.

Shields

The spearmen of

the paighan

infantry, and on occasion the foot archers, carried a large oblong, curved shield made from wicker and rawhide. The Dailami infantry are described by Agathias (3.7–9) as carrying shields and bucklers. This suggests a mix of types according to personal preference, but possibly tending towards a smaller, round type that could be used for skirmishing. However, it should be noted that Agathias describes these troops as being capable of both skirmishing and fighting at close quarters, so the evidence is not conclusive.

On the whole, the Sasanid horse archers did not carry any shields, relying upon the speed of their mounts to evade the enemy; but some of the allied cavalry contingents, such as the Alans, did carry a form of small buckler to enable them to compete in hand-to-hand combat. It may have been this that motivated the

savaran

to begin wearing a small buckler attached to the left forearm to help protect them when in battle. Yet this may also tie in to a change in outlook for the Sasanid heavy cavalry.

Horse Armour

The heavy defences of the earlier period of the Sasanid Empire were now in decline, possibly as a result of their experience fighting enemies such as the Huns and Hepthalites, who relied on mobility and firepower. The complete covering for horses found, for example, at Dura Europos, were being replaced by a

chamfron

(head) and

crinet

(neck) covering that protected only the head, neck and frontal chest areas of the horse. This marks part of the transformation of the

savaran

back into a force relying on archery followed by momentum and mobility to break the enemy, rather than simply their close-formation charge. Yet even these may have been in decline.

Weapons

Lances and Spears

The lances used by the

savaran,

and the spears used by some allied cavalry and the infantry, are likely to have resembled those used by the Byzantine cavalry of the same period. Unfortunately, none have survived to enable us to have a clear picture of their appearance, although depictions in art such as the basreliefs at Firzubad and Naghsh-e-Rustam give us some idea of their length and thickness, and the manner of their use.

As noted above, the Dailami troops are described by Agathias (3.7–9) as armed with ‘both long and short spears’.

Swords

The swords used by the Sasanids appear to have been long and relatively heavy, being

1–1.11

m in length and between 5 and 8.5cm in width. Unfortunately, excavated examples have been too corroded to allow a full reconstruction, so it is impossible to decide if they were designed mainly for either cutting or thrusting. However, there is a possible clue in the distinctive angled grip. This is very similar to the ’semi-pistol’ grip of the British 1908 pattern cavalry sword, which is generally considered the best sword ever issued to the British cavalry. This is partly because the 1908 sword was optimized purely for thrusting. The angle of the grip ensured that when the arm was extended, the blade naturally aligned with it, so there was a straight line from sword point to shoulder. As a consequence, when charging the sword was positioned to allow the rider to use the point at speed, effectively like a lance thrust, transmitting the full momentum of the horse into the blow; although this is not to say that it was not possible to cut with it too. It is worthy of comment that the Sasanids had the curved grip fifteen centuries before British sword makers, after a long drawn-out process and scientific study, arrived back at essentially the same solution.