Belle (21 page)

Authors: Paula Byrne

The district was only just becoming suburbia, and still had a rural feel. Much of the area was given over to market gardens. It was easily the largest area for vegetable produce on the north side of the river, so close to the densely populated streets of Westminster and the City of London.

6

Pimlico was a far cry from the splendours of palatial Kenwood and its luxuries, but Dido was now her own mistress, and mother to two boys. She had her own home, from which she could not be turned away, or hidden out of sight when visitors came. When she looked at her children it is probable that she felt a sense of belonging and kinship that was denied her at Kenwood. In the sugar islands, such children would have been categorised as ‘quadroon’, meaning they had three white grandparents and one black. But in London, Dido’s children would have something she never had: their legitimacy, and a home where they were raised by their own parents.

What was it like living in London as a mixed-race couple in the early years of the nineteenth century? In the absence of direct evidence about Dido’s experience of married life, we must look to other marriages. One of the better-known is that of Francis Barber, the trusted manservant and friend of the childless Dr Samuel Johnson. Johnson educated Barber, and made him his heir. Johnson’s opposition to slavery was well known: he once made a toast to ‘the next insurrection of the negroes in the West Indies’.

7

Johnson’s devotion to Barber is well documented, and many resented what they perceived as his sway over Johnson, just as people gossiped that Lord Mansfield was in thrall to Dido. Barber was born into slavery in Jamaica, but was raised and educated in England by his owner Colonel Richard Bathurst, who brought him from the West Indies. In his will, Bathurst confirmed Barber’s freedom, and left him a small legacy. Bathurst’s son helped to arrange a job for Barber as Johnson’s manservant, and he lived in Johnson’s household for thirty-four years. Their relationship was complex: Barber ran away several times, but always returned. Johnson had him taught to read and write so that he could act as his secretary, taking care of his correspondence and his manuscripts. Barber asked to read the popular novel

Evelina

, by Johnson’s friend Fanny Burney.

Barber, as Johnson noted with much amusement, was very popular with the female sex. One young woman, a haymaker, followed him to London from Lincolnshire ‘for love’.

8

But he married a beautiful white woman called Elizabeth Ball, and the couple and their children lived in Johnson’s house in Bolt Court, near Fleet Street.

Barber was fiercely jealous of his wife, and was only reassured of her fidelity when she produced a daughter ‘of his own colour’.

9

However, evidence suggests that the child was actually light-skinned, leading to much speculation and gossip: Hester Piozzi, Johnson’s great friend, noted cattily that Barber’s daughter was ‘remarkably

fair

’. It was rumoured that Elizabeth was a former prostitute, and that the children were not Barber’s. Barber’s jealousy of his pretty wife led Mrs Piozzi to refer to him and Elizabeth as Othello and Desdemona.

In fact, Frank and Elizabeth’s marriage was a happy one, and they produced three children. Their son Samuel became a Methodist preacher, and all three of them married whites, as did Dido’s children. Johnson expressed a desire that after his death the Barber family should live in his own home town of Lichfield, and their descendants still live there today.

Another mixed-race marriage was that of Olaudah Equiano (Gustavus Vassa), who married a local white woman called Susan Cullen in Soham, Cambridgeshire. They lived together happily and had two daughters. One of their children died, and the other, Joanna, married a Congregational minister. She inherited £950 on her father’s death, leaving her comfortably off. As the mixed-race daughter of a famous man, Joanna Vassa is the closest comparison to Dido that we have. Like Dido she married a white man and lived in London, although her first years were spent in Devon and Essex. She and her husband were seemingly devoted to one another, and were buried together.

The Barbers and the Vassas are examples of successful inter-racial marriages. One historian has noted that mixed-race marriages in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries ‘tended not to be seen as problematic to the English because they primarily occurred among the lower working classes’.

10

Most were between a black man and a white woman; unions between black women and white men were rare outside plantation life. The few examples tend to be found in the servant classes. Having money could actually be a disadvantage for a black woman in search of matrimony. A white footman named John Macdonald felt himself unworthy of a black woman called Sally Percival, not because of her race but because she was wealthy, having been left an inheritance by her former master.

11

Sally, Joanna and Dido were unusual because their relative wealth gave them status.

So what was Dido’s status in Pimlico as Mrs John Davinier? It is unlikely that she became part of London’s black community or even had black friends, as did Francis Barber. Her elder son Charles was sent to Belgravia House School, a respectable white establishment. Having been given an education, he was in a position to apply for work that might lead to a position as a clerk. He duly applied to the East India Company in 1809, when he was fourteen, naming his parents as John and Elizabeth Davinier, and stating that he was born in 1795. Little is known of the life of the younger brother, who bore the Lord Chief Justice’s Christian name.

Lady Margery Murray, one of the Mansfield nieces who had joined Dido in caring for the Earl in his final years, died in 1799, a ‘spinster of Twickenham’. In her will, proved on 9 May of that year, she left the sum of £100 to ‘Dido Elizabeth Belle as a token of my regard’. This will was written before Dido married, and a codicil dated September 1796 added an important modification: ‘The sum of one hundred pounds left in my Will to Dido Elizabeth Belle, she being now married to Mr Davinier, I leave the said hundred pounds for her separate use and at her disposal.’

12

Lady Margery evidently wanted the money to go to Dido herself, not to Davinier. This was the age before the nineteenth-century Married Woman’s Property Acts, so without such a stipulation the money would automatically have gone to Dido’s husband. Was Lady Margery worried that John Davinier might prove to be a gold-digger, more interested in Dido’s money than in loving and caring for her?

Dido did not live to see the abolition of the slave trade. She died in her early forties, in 1804, of unknown causes, and was buried that July in the St George’s, Hanover Square overspill burial ground on the Bayswater Road.

Four years later, John Davinier was living in spacious rooms above a baker’s on Mount Street, Grosvenor Square – still in the parish of St George’s, but at a more upmarket location than Ranelagh Street. The insurance policy for his property describes him as a ‘Gentleman’.

13

When he married Dido he was a servant. Now that he was a widower, thanks to her money, he had risen to become a gentleman – someone who did not have to work for a living.

The following year, Davinier had a daughter, Lavinia, by a white woman called Jane Holland. Three years after that, in 1812, the couple had another child, a boy, although it was not until 1819 that Davinier married Jane. The last sighting we have of Dido’s husband suggests that he returned to his native France: in 1843 his daughter Lavinia was married in St George’s church, and a newspaper noted that her father, John Louis Davinier, was of ‘Ducey, Normandy’.

14

Dido’s elder son Charles became an officer in the Indian army. Perhaps he was as brave and intrepid as his grandfather. He had a son, also christened Charles. But the Christian name that this boy used was the surname of Dido’s father. In 1901 he signed an Attestation upon joining the Canadian Scouts, part of the Imperial Irregular Corps, at Durban in South Africa.

15

He mentioned his previous service in the Boer War, including participation as a gunner in the Relief of Ladysmith. And he gave his name as Lindsay d’Avinière. While ‘d’Avinière’ is probably a reversion to the correct spelling of his surname, which had been phonetically rendered in English as the identical-sounding ‘Davinier’, the choice of ‘Lindsay’ as his Christian name suggests the family’s pride in their noble and military heritage.

Dido’s grave was moved in the 1970s, due to the redevelopment of the Bayswater area, and the location of the reburial of her remains is unknown. There is no grave to mark her life or death, and for many years she was utterly forgotten. The Kenwood portrait was moved to Scone Palace in Perth, and the family assumed that the beautiful black girl in the background was Elizabeth Murray’s maid. But many visitors to Scone today are irresistibly drawn to Dido, and want to know her story. Who is she? What is she doing in the portrait?

It was only in the 1970s and ’80s that research was undertaken, notably by Gene Adams, a local historian from Camden who immersed herself in documents associated with Kenwood, uncovering Dido’s deep connection to the house and the family. Her presence in the household, and Lord Mansfield’s adoption of her as a cherished daughter, ensured that he viewed the atrocities of the odious slave trade through a personal lens, through the eyes of a much-loved young black woman.

Jonathan Strong, James Somerset, Dido Elizabeth Belle. These were individuals, black people living in Georgian London, who helped to change history, but have been largely neglected. Mansfield knew that the fate of thousands of black people rested in his hands:

Fiat justitia ruat caelum

.

The horrors of the slave trade have receded into the past, though they have not been entirely forgotten. Britain is still a nation of sugar consumers, but not at the expense of a barbaric practice that destroyed the lives of millions of Africans. The economy of the Caribbean sugar islands now chiefly depends on tourism. In Jamaica, guests can dine at the famous Sugar Mill restaurant. In Antigua, tourists can rent the Sugar Mill Villa. Ironically enough, Dido’s last descendant, her great-great-grandson Harold Davinier, was traced to South Africa, where he died in 1975, during the apartheid era. He was classified as a white.

The 2014 feature film

Belle

, directed by Amma Asante and starring Gugu Mbatha-Raw, tells Dido’s story for the twenty-first century. Like all historical-biographical movies, it takes considerable artistic licence even with the few facts that we know about Dido. The

Zong

case, being more dramatic, is made the centrepiece of the courtroom drama, although the Somerset case was really the more significant for the abolitionist cause. And John Davinier becomes an idealistic clergyman’s son, with a little of the Granville Sharp about him, instead of a faceless French servant. But the spirit of the film is true to the astonishing story of Dido’s bond with Lord Mansfield.

Dido’s grave is lost, and she has no living descendants, but the painting once attributed to Zoffany remains as a testimony to her extraordinary legacy. Striding back from the orangery, perpetually in motion, gazing out boldly at the gazer, with her quizzical, dimpled smile, making no apology for her presence and her vitality. She lives on forever in this portrait, rising out of the darkness into the light.

Jane Austen’s Mansfield Connection

Eastwell Park, where Jane Austen met Dido’s adoptive sister

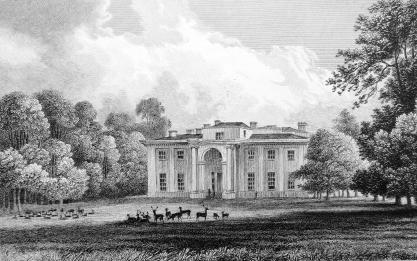

We do not know whether Dido ever visited Eastwell Park in Kent, Elizabeth Murray’s house after she was married. In order to make it a worthy home for a gentleman and his wife, in the 1790s George Finch-Hatton employed Joseph Bonomi, a pupil of the Adam brothers, to make improvements. Ground-floor wings were linked to the

piano nobile

of the main house by descending curved passageways.

1

With its high windows, classical portico and view out to picturesque landscaped grounds grazed by deer, the ‘improved’ Eastwell Park looks exactly like the kind of house in which we can imagine a Jane Austen novel being located –

Mansfield Park

, for example.

Jane Austen’s brother Edward, who lived in Kent, was a friend of the Finch-Hattons, and when she was staying with him in 1805 she visited Eastwell Park.

2

She was disappointed with Dido’s cousin: ‘I have discovered that Lady Elizabeth, for a woman of her age and situation, has astonishingly little to say for herself.’ She was equally unimpressed by Elizabeth’s daughter, but very much liked her young sons: ‘George is a fine boy, and well-behaved, but Daniel chiefly delighted me; the good humour of his countenance is quite bewitching.’ George grew up to be the rather impetuous young man who in 1829 challenged the Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington, to a duel; both men deliberately fired wide.