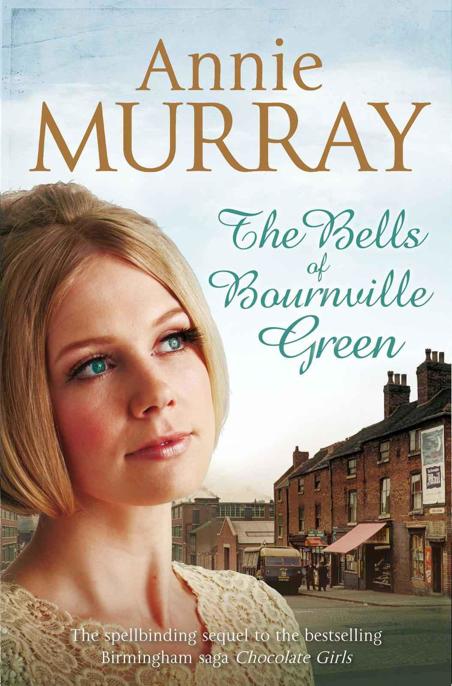

Bells of Bournville Green

Read Bells of Bournville Green Online

Authors: Annie Murray

A

NNIE

M

URRAY

The Bells of Bournville Green

PAN BOOKS

Contents

Part One

Birmingham, 1962–3

Chapter One

December 1962

‘What the flippin ’eck’s the matter with you two today? It’s Christmas isn’t it, not a wet weekend in Bognor?’

They were in the Girls’ Dining Room at Cadbury’s, which was decked out festively with streamers and tinsel. The young woman who had spoken, one of their group of pals, had plonked her soup down on the table and pulled up a chair beside Greta and Pat and the rest of them.

Greta looked up, managing to pull her round, pretty face into its infectious smile.

‘That’s better – yer enough to put me off my dinner – faces as long as Livery Street! Nothing up, is there?’

Greta didn’t want to say what was wrong. Quiet, steady Pat was her best pal from when she started at the Cadbury works three years ago, and she kept some things even from her. She didn’t feel like pouring out what had happened this morning in front of the rest of them: the row with Mom, the angry, bitter words.

‘Oh, I’m all right,’ she grinned. She always tried to be the life and soul. ‘It’s Pat here who’s down in the mouth.’

Pat never had it easy, and today her gentle face looked pale and strained.

‘It’s Josie – she was took bad last night. We didn’t get much sleep.’

Pat’s older sister Josie was severely handicapped and it was all Pat’s Mom could do to look after her. Pat carried a heavy burden of care as well. She was a quiet, sweet-natured girl with thick brown hair, always tidily fastened back for work, and a lovely dimple which appeared when she smiled.

‘What’s wrong with her?’ Greta asked carefully. Josie, a woman of twenty-one, could neither speak nor walk.

Pat shrugged. ‘Dunno really. You know what she’s like – she can’t say. She was running a fever but she was ever so restless all night.’

‘Poor thing,’ Greta said, her blue eyes full of sorrow for her friend.

‘Never mind, worse things happen at sea, eh?’ Pat rallied herself. She never liked to dwell on difficult things. ‘I’ll get this cuppa tea down me and I’ll feel better. I’m just a bit whacked, that’s all.’

‘I bet you are,’ one of the others said sympathetically. ‘You coming to the hop after? Do yer good!’

Every Monday there was a lunchtime dance in the Girls’ Gym, where they jived and bounced during the dinner hour.

‘Oh, not today,’ Greta said. ‘I’m not in the mood.’

‘Ooh dear – you have got it bad, Gret!’

‘Eh—’ Pat nodded across the room. ‘There’s your Mom. Ooh, look at her hair!’

Greta glanced round to see her mother, Ruby Gilpin, advancing across the dining room, like a ship in full sail. She worked at Cadbury’s three days a week, in the Filled Blocks section where there were a lot of part-timers. Buxom, pink-faced and smiling, she had given her hair a peroxide bleach yesterday and it crouched in startlingly bright, lacquered layers on top of her head. She was calling to one of her friends over by the long windows which looked out over the winter grey of Bournville Lane. She completely ignored Greta, as if she was invisible.

‘Can’t get away from the old lady, can I?’ Greta rolled her eyes comically. As usual she acted as if she had not a care in the world, though inside she boiled with hurt and anger. She could still hear the shuddering slam of the front door when she stormed out that morning. The rows had got worse lately, but there had never been one this bad before.

But Pat was watching her. ‘Is everything all right?’ she asked softly.

‘Oh yeah – course.’ She brushed it off, nudging Pat in the ribs. ‘Why wouldn’t it be?’

Pat’s life wasn’t easy, but she didn’t have a mother who had already got through three husbands and several other blokes since, so that you never knew who’d be there when you got home or what might be going on. Greta avoided taking anyone back to the house. God knows, if her employer had any idea how Ruby carried on she’d surely be out on her ear! Cadbury’s, who expected virtuous conduct from their employees based on their own Quaker principles, were very strict about drinking and moral behaviour, but so far Ruby had got away with it. And Greta was ashamed even to tell Pat all of it. Pat’s family had their problems, but Pat had grown up in Bournville, with an apple tree in the garden and piano lessons and a Mom and Dad with a couple of children. And Pat’s Mom looked after Josie beautifully.

Pat looked doubtfully at her but she wouldn’t push it, not in front of the others. She turned to look out of the long dining-room windows.

‘Looks as if it’s coming on to snow,’ Pat said.

‘A white Christmas,’ someone else said. ‘So they say.’

They ate up their soup and cobs and chatted about this and that. Greta and Pat were in the Moulding Block, on the wrapping machines for sixpenny bars of Cadbury’s Dairy Milk. One of their friends was on Chocolate Buttons, which had only been launched a couple of years earlier. Wherever they were working, though, they always tried to make sure they met for the dinner break.

They quickly cleared up their plates and headed off to put their overalls on again to start work, Greta trying to crack jokes and look cheerful. But Pat stopped her, a hand on her arm, pulling her out of the way of the stream of Cadbury women leaving the dining room.

‘You and your Mom had a bit of a ding-dong?’

Greta nodded, shaking her head fiercely because to her annoyance she felt her eyes filling. It all seemed to well up lately, all these angry, desperate feelings.

‘What – over

him?’

Pat winked. ‘Surely she can’t have anything against Dennis – he’s squeakier clean than a freshly washed window.’

Dennis, who worked at Cadbury’s maintaining the machines, was very sweet on Greta, as were several of the other lads, drawn by her curvaceous figure, her sunny golden-haired looks and lively personality. Of all the girls, she had the most attention from the Trolley Boys, who came by at the end of the production lines to take away the packed boxes of chocolate. Most of them were in their late teens and pestered the girls determinedly. Greta had had to learn ways to brush them off with a verbal put-down, as she got pestered more than most, though she enjoyed the spark of flirting with them as well.

Greta couldn’t keep it in any more. She needed to relieve her feelings. ‘Not Dennis!

Him

– Mom’s flaming latest – Herbie Small-Balls!’

She saw Pat crease up with giggles at this and couldn’t help joining in. Greta’s Mom’s boyfriends were always a source of mirth, but of all of them fat, balding Herbert Smail, who fancied himself as a big noise down at the Leyland works in Longbridge, had to be the worst of the lot.

‘Getting serious is it?’ Pat said, trying to contain her laughter and be sympathetic.

‘Yes – and it’s not

funny,’

Greta said, giggling unstoppably as well. She wiped her eyes, careful not to smudge her eye-liner.

‘Come on you two – quit yer tittering and get back to work,’ one of the older women said.

‘I’ll tell you later,’ Greta said gratefully as they headed back over to their block under the ominously grey sky, amid the drifting smell of liquid chocolate which they were so used to they barely noticed it any more. ‘But ta, Pat – you’ve cheered me up already.’

‘Glad to be of service,’ Pat said with a wink.

They went back to the belt by the wrapping machine, with its endless river of little bars of chocolate. Greta looked across at Pat, feeling a bit ashamed. Here she was, making heavy weather of her life when she sensed that Pat had more weighing on her than she ever let on either. She caught Pat’s eye and winked at her.

Where would I ever be without my pals? she thought.

Chapter Two

What had done it that morning was finding Herbert Smail sitting there large as life and twice as ugly at the kitchen table.

‘Morning, Greta,’ he said unctuously as she appeared, fortunately already dressed, instead of wandering down in her nylon nightie as she sometimes did for an early-morning cuppa.

Greta jumped, heart pounding. Refusing to look at him she went to the teapot, to find it had the dregs in it, still warm. She had no idea he was there! And now he’d very obviously spent the night in the house. The only blessing was she hadn’t heard anything – God what a thought!

‘You stricken with premature deafness by any chance?’ Herbert said, rather less pleasantly. He pronounced it ‘prema-tewa’, rolling his r’s in an affected way. He was one of those know-it-all types, thought he’d swallowed the dictionary. ‘I believe I was speaking to you – or was that just a figment of my imagination?’