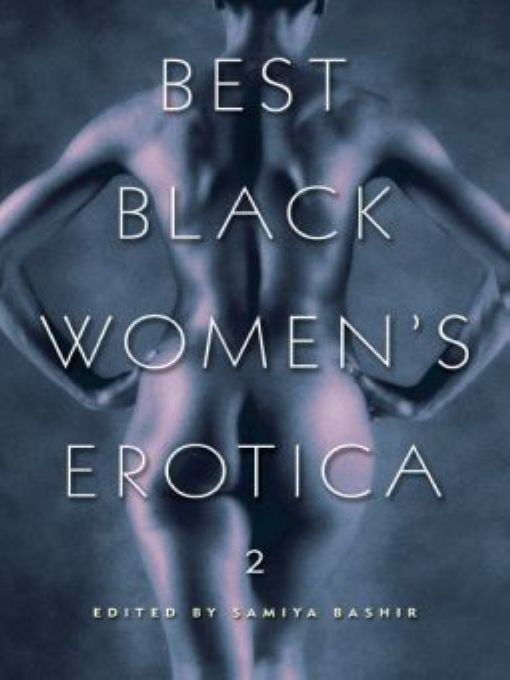

Best Black Women's Erotica 2

Read Best Black Women's Erotica 2 Online

Authors: Samiya Bashir

Table of Contents

Â

Â

Â

For my grandmothers, my mothers, my sisters, and my aunts. For all the women whose love of life and zest for loving fully and completely informs me. For the freaky black girls everywhere who continue to liberate our bodies and our minds.

Love is lak de sea. It's uh movin' thang, but still and all, it takes its shape from de shore it meets, and it's different with every shore.

âZora Neale Hurston,

Their Eyes Were Watching God

Their Eyes Were Watching God

Â

Â

Please get over the notion that your particular “thing” issomething that only the deepest, saddest, the most nobly tor-

tured can know. It ain't. It's just one kind of sexâthat's all.

And in my opinion, the universe turns regardless.

âLorraine Hansberry

Introduction

Samiya A. Bashir

Â

Â

Â

Â

Touch. Like the pages of this volume, we all need to be touched, caressed, flipped, turned, and read with passion. Our senses need inspiration to open and flare, to allow the flow of sensory input, ever present in our world, to wash through our bodies and into the spiritual realm housed within. All too often we go through our everyday lives, accepting an increasing amount of input and information, rarely even stopping to filter it, or (rarer still) insisting on that input which strokes and kisses our imaginations.

I hope that this collection does just that. I hope these stories stretch their tender fingertips to touch you, the reader, in ways that force you to stop and enjoy the sensation. In compiling and constructing this second edition of

Best Black Women's Erotica,

it was important both to be true to the scope of the series and to offer something unique in the process. As I accepted this challenge I reached back to mine my own trunk of memories. I wanted to find not only moments of change and growth, but the inspiration for those moments. What I found illuminated the idea of difference. In this collection, it was

important for me to present as wide a berth of black women's experience as possible. The rangeâwhich covers age, region, physical ability, sexual orientation, identity, and the multiple types of relationships we create for ourselvesâhopes to provide a mirror for some women, and a window to others.

Best Black Women's Erotica,

it was important both to be true to the scope of the series and to offer something unique in the process. As I accepted this challenge I reached back to mine my own trunk of memories. I wanted to find not only moments of change and growth, but the inspiration for those moments. What I found illuminated the idea of difference. In this collection, it was

important for me to present as wide a berth of black women's experience as possible. The rangeâwhich covers age, region, physical ability, sexual orientation, identity, and the multiple types of relationships we create for ourselvesâhopes to provide a mirror for some women, and a window to others.

Best Black Women's Erotica 2

includes twenty stories written by women from diverse backgrounds, each with a unique story to tell. The volume opens with “Rhythm,” Donna Sherard's examination of the erotic in everyday experience. The story takes one woman, getting her hair braided by two experts while waiting for the return of her lover, into the dreamworld of fantasy, led by touch.

includes twenty stories written by women from diverse backgrounds, each with a unique story to tell. The volume opens with “Rhythm,” Donna Sherard's examination of the erotic in everyday experience. The story takes one woman, getting her hair braided by two experts while waiting for the return of her lover, into the dreamworld of fantasy, led by touch.

Opal Palmer Adisa and D. H. Brent craft characters for whom the relationship is not the point, or so they hope; the point is the need to be fulfilled, to feel as the light inside the spark. Camille Banks-Lee, folade mondisa speaks-love, and Michele Elliott imagine relationships that celebrate their sexual selves. Love is explored through the telephone wires and Internet cables, inspired by music and film, and takes place in spaces at once familiar, changed, and completely new. “Palimpsest,” by R. Erica Doyle, takes readers' expectations, and any last grasp at taboo, and puts them through the spin cycle, tumbling faster and faster until they jerk to a stop, and come out hot, changed, slightly singed, and with the smell of rebirth.

The things that we choose to eroticize also speak volumes about how we filter all that input. Robin G. White's story of a gospel organist and her congregant, “Shout,” draws a direct line between the physical and the spiritual, inviting readers to “feel the spirit” in a whole new way. Tracy Price-Thompson mines a driving need that pushes far past fleeting lust to find strength in the desolation of a desert war. In “Shared Heat,” she brings together a photographer and an infantry commander leading his troops to a hopeless and probably

pointless death. Their near-wordless exchange must pack the explosive passion of a lifetime into one cold, silent night. Kimberly White looks into a future where the line between the breath of life and the blink of automation merges with a woman and her made-to-order lover.

pointless death. Their near-wordless exchange must pack the explosive passion of a lifetime into one cold, silent night. Kimberly White looks into a future where the line between the breath of life and the blink of automation merges with a woman and her made-to-order lover.

Throughout this collection, the senses are engaged. In Kiini Ibura Salaam's “Kai Does Redâ¦Again” the story is told to the backbeat of the club music threatening to burst through the bathroom door. Tara Betts explores the sense of sound and the sensuality of speech in “Talk to Me.” Janeé Bolden uses hip-hop as a metronome, and Dorothy Randall Gray's full, powerful, and sensual “Miss Cicero” finds her passion reading Zora Neale Hurston to a longtime friend. In the end, Carol Smith Passariello uses the photographer's lens to break through the barriers of fear and shame as a group of friends learn together how to find their own inner and outer beauty.

Take it in all at once, or stretch it with slow, savory sips. Let the stories enfold you for a moment, let them touch and stroke you, body and spirit. Drink them in, spit them back out if you like, but savor the taste. These stories will have you coming back for more.

Samiya A. Bashir

New York

December 2002

New York

December 2002

Rhythm

Donna Sherard

Â

Â

Â

Â

Living in Kampala requires patience to learn to flourish within the rise and fall of natural movements that mark the passage of the day. Watches are rendered unnecessary. Each day falls into a calculated and undulating rhythm. To the newly initiated, this rhythm creates what may seem to be a haphazard and unplanned environment, regularly punctuated by daily electricity outages, quizzical traffic patterns, and phone delays. I have just begun to realize, however, that only a fool would try to define or label this city as anything abnormal or disorganized. I have begun to understand that life in in Kampala, and especially during the rainy season, is managed by a seductive rhythm guided by daylight and rain that is very methodical, indeed. I have also had to come to terms with the reality that living here happily requires adjustment to this rhythm. Everything here moves to the calculated staccato, yielding a magic that can only be described as both expected and yet very unexpected.

Every day, Kampala's rhythm starts at just before sunrise when something in the easy breeze encourages the rooster,

owned by the neighboring guesthouse, to croak his morning alarm. After three weeks of mornings here with Daudi, I have come to understand the wakeup pattern of our cackling neighbor. His voice is comically rusty at first, sounding almost like a human imitation. Soon after his warm-up, however, his lubricated and lusty vocal cords break out into full alto vibrato that sounds from within the confines of his breast, and screams through his beak.

owned by the neighboring guesthouse, to croak his morning alarm. After three weeks of mornings here with Daudi, I have come to understand the wakeup pattern of our cackling neighbor. His voice is comically rusty at first, sounding almost like a human imitation. Soon after his warm-up, however, his lubricated and lusty vocal cords break out into full alto vibrato that sounds from within the confines of his breast, and screams through his beak.

This Friday, this day fourteen of my twenty-eight-day cycle, also began with the familiar moist pressure in my loins that accompanied the rooster's orchestrated cries. Thirty was seemingly now a curse, as sex for me had lost some of its wild abandon. My innate, physical desire “to get some” was usually now at its greatest crescendo only when I was also feeling the pinch of ovulation. This morning, and in its own timely rhythm, nature's desire to reproduce woke me with an insuppressible and very hopeful horniness. The hopefulness was, unfortunately, irrelevant, for this morning was different. Daudi wasn't here. Having traveled home to Nairobi for work almost a week ago, he wouldn't be coming back until well after Kampala's day's end, long after sundown, and long after the pungent smell of smoking rotâFriday's burned garbageâhad blown to the bottom of the hill.

Today was also the first day of the rainy season, and while it had not yet rained, its promise left our bedroom humid. The still uncooled mid-April heat made the mosquito net feel thick as cheesecloth. I lay still as my overactive imagination felt Daudi's fingers moving up my legs and, finding the joining of my thighs soaking wet and my clitoris hard as tanzanite, he would then straddle me and we'd make love. I was left to merely imagine, however, to bookmark that thought for this evening. Lying spread-eagled across our bed reminded me, again, that he was still not here.

Before he left on Monday we had lain on this same bed

together, still sweaty and nude from our preliminary good-byes. I watched his profile as his lips spilled a litany of of concerns about leaving me alone, in his deep Kikuyu accent. This one week would be our longest separation since I had returned, and he sounded frighteningly like my father.

together, still sweaty and nude from our preliminary good-byes. I watched his profile as his lips spilled a litany of of concerns about leaving me alone, in his deep Kikuyu accent. This one week would be our longest separation since I had returned, and he sounded frighteningly like my father.

“Remember to call Wamala if you need to go anywhere, and please don't forget to lock the car doors at the roundabouts. Can you remember to close the windows at night and spray the room and turn on the mosquito zappers?”

Daudi was forever worried about my falling victim to crimes usually reserved for Muzungus and other foreigners in traffic, and he took my Michigan bloodâand the fact that it had not yet been baptized with malariaâas his single greatest responsibility.

“Babes, I will be fine,” I had assured him.

In actuality, while not at all terrified at his leaving me alone in this house shortly after my relocation here, I had struggled with the onset of two emotions: first, hating that we were about to be separated even for a week so soon after our previous nine-month hiatus, and second, hating the fact that I was feeling so damn needy.

Last Monday, the prospect of the one-week separation had seemed like a lifetime, and I was now emotionally and very physically anxious for his return. Daudi and I, both far too cynical to have pet names for our body parts, never baptized his penis or my vagina with any names other than “dick” and “pussy” (words whose meanings had thankfully transcended our cross-cultural backgrounds). Today, I could think of nothing but their reacquaintance as I opened my eyes on this Friday. With the persistent throbbing in my crotch bordering on ridiculous, I allowed a fleeting thought of quenching my own thirst through a brief tangle with my makeshift soapstone dildoâoriginally, a mildly phallic-shaped figurine Daudi had brought me from Nairobi. I quickly changed my mind as I

remembered that for the past three nights, this had already proved to be an unsatisfying option. While certainly hard, the figurine never seemed to get warm enough, and certainly didn't vibrate like “Pinky,” whom I had left in the States for fear of embarrassment at the Ugandan customs inspection. Although I smiled to myself at the thought of the soaking-wet welcome Daudi would come home to tonight, I somehow knew that my decision to not masturbate away my inflated libido this morning would have its own frustrating consequences.

remembered that for the past three nights, this had already proved to be an unsatisfying option. While certainly hard, the figurine never seemed to get warm enough, and certainly didn't vibrate like “Pinky,” whom I had left in the States for fear of embarrassment at the Ugandan customs inspection. Although I smiled to myself at the thought of the soaking-wet welcome Daudi would come home to tonight, I somehow knew that my decision to not masturbate away my inflated libido this morning would have its own frustrating consequences.

The sun, now close to full throttle, decorated the bedroom with stripes as it passed through the glass-levered windows. The rooster's cacophony had now yielded to the next round of sounds that marked the slow unfolding of the morning. They began in perfectly timed succession with the barking of the German shepherds that volunteered to guard the neighboring Kabira School. The dogs knew, by the tilt of the sun, when breakfast would be tossed at them through the kitchen doors. At the same time, our version of a motorized rush hour passed with the buzzing sound of the moped

boda-boda

taxis that ferried neighbors to the more well traveled Kironde Road. I knew that as they became less frequent it was getting past any acceptable time to get up. My punishment would certainly be meted out if I still found myself lying here unwashed and unfed to hear the slight click of the daily, induced off-cycle of our electricity, and the whirring swell of the generator next door, indicating the end of hot water and the ability to cook my breakfast, not having a generator ourselves. Again, slow to adjust to Kampala's own means of telling time, I still had to confirm through a roll of my body toward the bedroom digital clock what this city already knew, that it was eight A.M., just one hour before my nine o'clock appointment with the hair braiders.

boda-boda

taxis that ferried neighbors to the more well traveled Kironde Road. I knew that as they became less frequent it was getting past any acceptable time to get up. My punishment would certainly be meted out if I still found myself lying here unwashed and unfed to hear the slight click of the daily, induced off-cycle of our electricity, and the whirring swell of the generator next door, indicating the end of hot water and the ability to cook my breakfast, not having a generator ourselves. Again, slow to adjust to Kampala's own means of telling time, I still had to confirm through a roll of my body toward the bedroom digital clock what this city already knew, that it was eight A.M., just one hour before my nine o'clock appointment with the hair braiders.

Other books

After Caroline by Kay Hooper

Where the Streets have no Name by Taylor, Danielle

The Best Casserole Cookbook Ever by Susie Cushner

Love's unending legacy (Love Comes Softly #5) by Janette Oke

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest by Ken Kesey

Prepper's Crucible - Volume Six: The End by Andrews, Bobby

Found: A Matt Royal Mystery by Griffin, H. Terrell

Cold Bullets and Hot Babes: Dark Crime Stories by Arlette Lees

The Rush by Rachel Higginson

Divine Design by Mary Kay McComas