Bette and Joan The Divine Feud (23 page)

"While waiting on the set she knits as she reads, and chews a half stick of gum," said another publication. "Her gum-chewing is audible and at times she cracks the stuff between her teeth. She also smokes." Hopeful that this film would restore her popularity, when asked if she minded the games and infighting that went along with being a star in Hollywood, Joan replied, "Honey, I thrive on that stuff."

Photographed in black and white, the look and the mood of

Mildred Pierce

would later be hailed as a forerunner in Warner Bros.'

film-noir

period. Although the European influence of low-key lighting and unusual camera angles had already been used in

The Maltese Falcon, High Sierra,

and Bette Davis'

The Letter,

it was Joan Crawford's

Mildred Pierce

(followed by

Humoresque, This Woman

Is

Dangerous,

and

Sudden Fear)

that drew the most praise from art critics and enthusiasts. The importance of the moment, however, was lost on the star. "The first time I heard the words

film noir

was in New York," said Crawford. "I was being interviewed by a critic of the 'cinema,' which, as you might know, has nothing to do with the 'movies.' He kept talking about this

film-noir

style and I didn't know what the hell he was talking about. When it came up again sometime later, I called Jerry Wald and I said, 'Darling, what is this

film-noir

style they're all talking about?' He explained it to me, which made me appreciate the film even more. I already knew what a terrific bunch of guys we had on that picture. They weren't just artists, they were geniuses."

It was Ernie Haller, who had photographed Bette Davis in

Jezebel

and Vivien Leigh in

Gone with the Wind,

who was solely responsible for the visuals in

Mildred Pierce,

said Crawford. "Ernie was at the rehearsals. And so was Mr. [Anton] de Grot, who did the sets. I recall seeing Ernie's copy of the script and it was filled with notations and diagrams. I asked him if these were for special lights and he said, 'No, they're for special shadows.' Now,

that

threw me. I was a little apprehensive. I was used to the look of Metro, where everything, including the war pictures, was filmed in blazing white lights. Even if a person was dying there was no darkness. But when I saw the rushes of

Mildred Pierce

I realized what Ernie was doing. The shadows and half-lights, the way the sets were lit, together with the unusual angles of the camera, added considerably to the psychology of my character

and

to the mood and psychology of the film. And that, my dear, is

film noir."

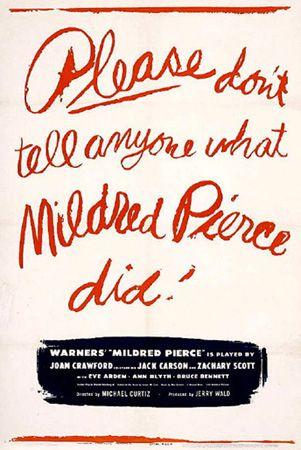

"Mildred Pierce .

..

Loving her

is liking shaking hands with the

Devil. She gave more in her

glance than most women give in

a lifetime. Ssssh

...

Please

don't tell what Mildred Pierce

did."

—AD LOGOS FOR THE FILM

In September 1945 Crawford's comeback film was released, to almost unanimous acclaim for the actress. "Sincere and affecting," said the New York

Times.

"A magnificent performance," said

Life.

James Agee of

The Nation

found the film "gratifying," with Joan Crawford "giving the best performance of her career." Paying close attention to the James Agee review was another leading actress of that day—Bette Davis.

Bette had a major film released a short time before Crawford's—The

Corn Is Green.

The budget was twice that of

Mildred Pierce,

with Davis re-creating the role played by the great Ethel Barrymore on Broadway. Her film was serious art, while

Mildred Pierce

was cheap trash, Davis felt. But the critics, led by James Agee, did not hail Bette as Miss Moffat. Calling Davis "sincere and hardworking," Agee said that the actress as the elderly schoolmistress was "limiting herself beyond her rights, by becoming more and more set, official, and first ladyish in mannerism and spirit, which is perhaps a sin as well as a pity." ("That shit doesn't know

anything

about acting," said Bette, "and furthermore he's illiterate.")

But the audiences seemed to concur with Agee. They stayed away in droves from

The Corn Is Green,

while

Mildred Pierce

posted a "Sold Out" sign at all first-run houses. By the end of the year Joan's picture had outgrossed Bette's three to one. More ignominy for Davis would follow.

In December, Warner's pushed both pictures for Academy Award consideration in all categories. When the nominations were released,

Mildred Pierce

received seven, including Best Picture and Best Actress for Joan.

The Corn Is Green

received two, with nothing for Bette, who was far from thrilled to be knocked off the annual honors list by Joan Crawford. "If you value your life," said Hedda Hopper in her column of January 26, "do not bring up the name of Joan Crawford in Queen Bette's presence."

Louella Parsons was also shocked by the monarch's behavior. "I can hardly believe that Bette Davis is being as rude to Joan Crawford as the spies on the Warner's lot tell me," she said in her Hearst column. "Bette's always been swell about extending the welcoming hand to visiting stars and young players," Parsons explained, telling her readers how Joan went up to Bette's table in the Warner's commissary and extended an invitation to a dinner party. "While Joan stood there, Bette kept eating and barely looked up, and never invited Joan to sit down."

"Maybe she had something on her mind," said Sheilah Graham, reporting the same story.

"I'd hate to think," said Parsons, "that such unusual conduct is because Bette, who is the only actress to win an Academy award at Warner's, is not even in the running this year."

"What a fat silly bitch," said Bette of the columnist, banning her from visiting her set for two years.

Oscar Night

The war was over and the dress code for the night was black-tie formal. To accommodate the crowd of 2,048 guests, the ceremonies were held at Grauman's Chinese Theater. Among the early arrivals were Jane Wyman and Ronald Reagan, Myrna Loy, Frank Sinatra, Guy Madison, Diana Lynn, and Bette Davis, who was not campaigning for Joan.

"You

are going to win," Bette told the candidate from

The Bells of St. Mary's,

Ingrid Bergman. "I voted for you." Also present at the ceremonies were Best Actress nominees Greer Garson

(Valley of Decision),

Jennifer Jones

(Love Letters),

and Gene Tierney

(Leave Her to Heaven).

The fourth nominee, Joan Crawford, was absent, at home in bed with the flu and a bottle of Jack Daniel's bourbon.

"I fortified myself a little too much," said Joan, who lost twelve pounds from stress and anguish the week before the show. "I was hopeful, scared, apprehensive, so afraid I wouldn't remember what I wanted to say, terrified at the thought of looking at those people.... I was never good enough for the Fairbanks, Srs., for Mayer."

She really thought she'd lose, that Ingrid Bergman would win. "I can compete with a servant girl [Greer Garson], with a tramp [Gene Tierney], an amnesiac [Jennifer Jones], but not with a nun [Ingrid Bergman]," said the nervous nominee.

Wearing a nightgown designed by Helen Rose, Joan listened to the show over the radio, then "took a deep breath" when Charles Boyer read off the names of Best Actress nominees. When he announced the winner ... "Joan Crawford," she exhaled with a scream that alerted the newsmen on the lawn below her window that she had won. Jumping out of bed, the ailing star then called for her hairdresser and makeup man, on call in the next room.

"The celebration went on all night," she recalled. "Mike Curtiz arrived with the award, followed by dear Ann Blyth, whose back had been broken in a tobogganing accident a short time before. The phone never stopped ringing. Eventually we had to take it off the hook. Then, at eight o'clock the next morning, the flowers and telegrams began to arrive."

That morning the newspaper photos of Joan receiving her Oscar in bed "pushed all the other winners off the front pages," said Hedda Hopper. At noon Louella Parsons arrived to congratulate "Our Own Joan" personally. "Trailing a black negligee, with her flaming hair high on her head," the star received Parsons in her library, and the two read telegrams to each other. The messages came from extras (the first year they could vote), carpenters, the switchboard operators at M-G-M and Warner's, and from industry notables. "I am so happy for you," said Ingrid Bergman. "I voted for you and not Greer Garson," said her old boss, Louis B. Mayer. "We are all so proud of you," said her new boss, Jack Warner.

Among the yellow-backed telegrams, some four hundred in all, Louella couldn't help noticing that one was from ... Bette Davis. "Isn't that sweet," said Joan, reading the one-word composition from Bette, "Congratulations."

"There is no feud," Joan told Parsons. "My heart is too full. Certainly there is room for both of us at Warner's. We may even do a picture together."

"When hell freezes over," said Bette, when apprised of this news. "One comeback performance does not constitute a career," she commented to a studio publicist that same day. As far as she was concerned, Joan's Oscar victory was a fluke. It changed nothing. She was still the number-one star at Warner's. Having recently set up her own production company at the studio, she was geared to make four films in a row, including

Ethan Frome, Lady Windermere's Fan,

and

The Life of Sarah Bernhardt.

But none of these films would be made; and Joan Crawford, with her Oscar held aloft, would proceed to reap more power and prestige at the Warner's studio. As her star ascended again, Bette's declined. The feud between the two Queens had just begun.

PART TWO

The Years

1946-1977

12

"To be an actor it is essential to

be an egomaniac; otherwise it

doesn't work."

—DAVID NIVEN

I

n the months prior to Joan Crawford's Oscar victory, Bette Davis had more important things to push around on her professional plate than worrying about the threat to her throne from an outsider. In 1945 Bette had been named the highest-paid female in America. Her salary for the year was $328,000 (compared with $156,000 for Crawford), but due to high taxes she kept only ninety thousand of that sum. On the advice of her lawyer and her agent, to save on taxes and to keep tighter control over her film work, Bette formed her own film production company, B.D. Inc. She owned 80 percent; her agent, Jules Stein, got 10 percent; and the remaining ten shares were split between her lawyer and her mother. Warner's would continue to finance and release her movies, and Bette the actress would be paid her star salary upfront, but Bette the producer would receive 35 percent of the profits after production costs were recouped. "Maybe now when she is spending her own money, she'll adhere to a schedule," said Jack Warner hopefully.

The first picture released under the B.D. Inc. banner was

A

Stolen Life,

with Bette acting opposite herself in the lead roles. Playing identical twins, Bette as Kate the good sister was timid and soft-spoken and wore plain clothes. As Pat, the bad sister, she sneered and smoked, and for her sins was drowned at sea—then replaced, in her wealthy home and marital bed, by sister Kate.

Although the film was set in New England, Bette the producer, for time and convenience, decided to shoot the exteriors at Pebble Beach, California, and at Laguna Beach, where she erected an East Coast lighthouse not far from her home. In the studio, Bette the artist insisted on absolute realism in every aspect. She didn't like the dog that Central Casting provided for one scene. "It can't be

any

dog," she explained to Central Casting. "When I decide to impersonate my dead twin sister, the dog knows I'm an impostor when he

smells

me. For that we need a dog that can act."

"She spent an entire day auditioning dogs," the director, Curtis Bernhardt, recalled. "Every professional and semi-professional canine in Los Angeles was brought into Warner's. Big dogs, small dogs; poodles, schnauzers, cocker spaniels, collies; they were paraded in and out for her inspection all day long. The street outside the soundstage was covered with dog-doo. Eventually she picked a wire terrier, but when they got to shooting the scene the little thing was terrified of Bette. He wouldn't go near her; let alone smell her."

Finding a leading man for

A Stolen Life

was also arduous for Bette. For the role of Bill, the handsome lighthouse inspector, the studio insisted she use one of their contract players. She was given her choice of Dennis Morgan or Robert Alda. Morgan, the perennially smiling matinee idol, was too handsome; and the suave, dark-haired Alda (father to Alan), who had just starred as George Gershwin in

Rhapsody in Blue,

looked too much like "a Jewish gigolo," said Bette. It was director Bernhardt who suggested an actor recently discharged from the Army, Glenn Ford. Some Columbia footage of Ford was run for Bette. "Yes! I like

that,"

she said and asked that he test with her. "There was some resistance from Jack Warner," said Harry Mines (who had previously arranged that hot romance between Glenn Ford and Joan Crawford). "Warner didn't want to hire an outsider. So I had to smuggle him onto the lot in the back of my car. Glenn made the test with Bette and she told Warner that she had to have him. So the studio paid something like seventy thousand dollars to Harry Cohn to borrow him."

Ford was thankful for the chance to work with such a big star as Bette Davis, but not grateful enough to carry their love scenes off-camera. Unlike the seductive and lovely Miss Crawford, the supreme Bette was not successful in establishing a personal relationship with the young actor. He was already romancing another star, M-G-M dancer Eleanor Powell. "Bette was very enthused about Glenn Ford at the start of the picture," said director Bernhardt, "but once she found out that he was taken by Powell, she became quite cool and businesslike. She never let him know of her feelings, but she made it miserable for everyone else on the set."

"It was

not

a happy picture. There were many obstacles and upsets to overcome," said Bette, referring in part to the latest in a series of "strange mishaps" she suffered during this time.

Cracked toes, rope burns, twisted ankles, cactus needles in her rear—these were a few of the on-the-job travails suffered by Bette Davis during the production of her movies. Two years before, shortly after Joan Crawford moved in next door to her at the studio, Bette was the victim of what she called a malicious act. During the production of

Mr. Skeffington,

someone went to the star's dressing room and tampered with her special eyewash. Due to the glare from the bright lights, the actress was accustomed to washing her eyes out between scenes. Throwing back her head, she emptied the solution in her right eye and immediately began to scream. Her eye was burning. Her makeup man, Perc Westmore, rinsed out the eye with castor oil, and Bette was taken to the dispensary. The eyewash, when analyzed, was found to contain a deadly fluid known as acetone. Bette demanded that an immediate investigation be made. But when the head of security asked production chief Steve Trilling if anyone on the set of the turmoil-ridden

Mr. Skeffington

was a suspect, Trilling replied, "If you were to line up the cast and crew and ask them: 'OK, which one of you wanted to kill Bette Davis?'—a hundred people would raise their hands."

Walking down a street while filming

The Corn Is Green,

Bette was injured again when a small rock fired from a slingshot hit her on the calf of her leg. Shortly thereafter, while Joan Crawford was on an adjoining soundstage testing for

Mildred Pierce,

a second, more serious injury occurred. Bette was standing on her mark for a scene when a heavy steel cover from an arc light in the crosswalks above came crashing down and hit her on the head, which was protected at the time by the hat and wig she was wearing for her role as Miss Moffat. To alleviate the tension, one of the camera operators, knowing of the antipathy between the star and Crawford, looked up at the flies and yelled, "Is that you up there, Joan?"

Bette screamed, "That is

not

funny!" and walked off the set.

"She suffered from nerves, nausea and severe migraines for weeks," a production memo stated.

During the making of

A Stolen Life,

Crawford was three thousand miles away, on vacation in New York, when Bette smashed her thumb in a faulty door. This meant an absence from the set for two days—"during which the bastards docked me for two days' pay." While she was driving home on a subsequent evening, a careless driver smashed into the rear of her new car, slamming Bette into the windshield. Her headaches increased. On the set the following week, the process shots for the storm sequence of the film were photographed in a huge water tank on the back lot. For the scene where bad sister Kate was drowned at sea, the star asked for repeated takes. Sitting in a boat in the immense tank as the giant wind machines churned up fifteen-foot waves, Bette when cued was washed overboard. On the third take, however, she failed to surface. Her feet got caught in the underwater wires and as she struggled desperately, "convinced she would drown in seventeen feet of water," a frogman was dispatched to find her. "I thought we had lost you," director Bernhardt said when the actress finally surfaced. "Why didn't you dive in and see, you son of a bitch!" a wet and livid Bette replied.

"Bette is outspoken and 95

percent honest. There always has

to be a margin for untruth. She

doesn't like to hide the fact that

she likes and welcomes sex. 'But

it is only work that satisfies,'

she says."

—SIDNEY SKOLSKY

On October 12, 1945, two months after World War II officially ended, Bette attended a gala party at the studio to welcome Ronald Reagan, Wayne Morris, Gig Young, and others home from the war. The guest list totaled four hundred, and although Bette appeared to be smiling in the photos with the happily reunited families and engaged couples, inside she was suffering from an acute case of the blues. With the war over, she was feeling alone and abandoned. Her last, and lengthy, romance—with an Army man she met at the Hollywood Canteen—began to wane when he shipped out without placing a requested engagement ring on her finger. (Shortly thereafter, when the soldier was in battle in Europe, Bette dispatched a "Dear John" letter to him at the front. "The news upset him greatly," she said, "and I was pleased.") To add to her loss, the Canteen was about to close, while another diversion and steady companion, her mother Ruthie, had remarried that same week. At thirty-eight, with her biological clock ticking away, Bette Davis was indeed the studio's top star and America's highest-paid female, but she had no lover, husband, or children to share the renewed bliss of peacetime with. Resourceful, however, and always forward, not to mention impetuous, she would fill up that void within thirty days.

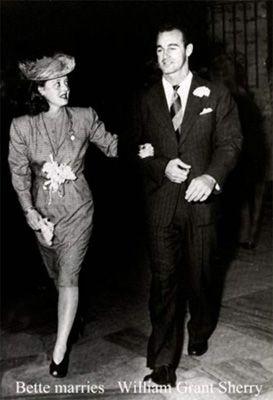

On Saturday night, October 20, Bette attended a party at a neighbor's house in Laguna Beach. "The moment I arrived, a very attractive man brought me a drink and never left my side," she said. His name was William Grant Sherry. He was tall, well built, and soft-spoken. Six years her junior, he was a sailor on leave from the naval hospital in San Diego. "Weekends I would hitch up to Laguna Beach," said Sherry. "I met Bette at the party and we took to each other immediately. We had a lot to talk about, both being from New England. She was interesting, not pretty but attractive and down to earth."

Bette told the good-looking sailor she was an actress. "Neither she nor anyone else mentioned Hollywood, and since she was in Laguna Beach, I figured she belonged to the local theater group," he said. "The name Bette Davis didn't ring any bell in my mind. She was simply a gal I suddenly had a deep romantic feeling for."

Discharged from the Navy two weeks later, Sherry went back to Laguna to pursue a career as a fine-arts painter. "I hoped to see Bette, and I did. She was living there in a simple beach house that I thought belonged to her mother. Nothing indicated she was a movie star, and she never mentioned it. We spent days and most of the nights together."

'Actually I liked the way he looked on the beach in a pair of shorts," she told Sheilah Graham when the columnist reported on the romance.

"Three weeks later I proposed to her and she accepted," said Sherry, "but she said she had to go to Mexico on business, and that we would get married on her return. I convinced her we should get married and drive down together as part of our honeymoon. We got our license in Santa Ana. At the wedding the next day I couldn't believe the invasion of news people and photographers. I was a little stunned and said to Bette, 'Who are you anyway?' She just laughed her hearty laugh."

On a highway outside Mexico City, the groom soon learned who his bride was. "We were late getting to Mexico City, because the tires blew out on our car due to the hot roads. We were sitting on the roadside wondering how we were going to get to town when an army of cars filled with police and officials arrived. When they saw Bette, there was much cheering and handshaking. We were transferred to a big limousine, which drove us into Mexico City. On the way, Bette explained that the Mexican government was using her film

The Corn Is Green

for their illiteracy campaign. It was then I realized she was more than a local actress. I had to explain to her that I never saw any of her movies and she thought that was a huge joke."

In Mexico City the couple were driven to a nightclub, where Bette was given the keys to the city. When they arrived finally at their hotel, her maid from the studio had already prepared their bed in the bridal suite. "The bed was turned down, with my pajamas lying beside Bette's nightgown," said Sherry. "I stood there looking down at Bette and I got very sentimental. It was a beautiful dream. I had a wonderful wife."

"Oh, Sherry," said Bette, "you big sap."

After their stay in Mexico City, where they dined with the President, Dolores Del Rio, and Mary Astor, the couple returned to Los Angeles, where Bette had the studio run off some of her films for her new husband. One afternoon, while he was walking to the Warner's parking lot, a beautiful lady spotted him from the other side of the street. It was Joan Crawford.