Bette and Joan The Divine Feud (4 page)

Joan Goes Straight

"I had always known what

I wanted, and that was beauty

. . . in every form ... a

beautiful house, beautiful man,

a beautiful life and image. I was

ambitious to get the money

which would attain all that

for me."

—JOAN CRAWFORD

Upon the signing of her new contract with M-G-M, Crawford's salary was raised to fifteen hundred dollars per week, with an upfront bonus of ten thousand. She became a member of Louis B. Mayer's ("Call me Papa") family of stars, which also included Lon Chaney, Buster Keaton, Norma Shearer, and Greta Garbo. Crawford was now entitled to receive all of the privileges and protection that the powerful studio could offer. In Joan's case the latter service proved beneficial. She had already been involved in a few legal skirmishes with stores in Los Angeles. Once she was apprehended leaving a woman's specialty shop with merchandise not paid for; another fashion establishment claimed that Mrs. Anna LeSueur, her mother, ran up bills that she refused to pay. Joan had already been cited twice by the Los Angeles Police Department for speeding when a third, more serious infraction occurred. She was driving at a rapid pace along Hollywood Boulevard, ignoring the red lights, when she hit a woman crossing the street. Attempting to leave the scene of the accident, she was apprehended by a policeman. Bursting into tears, Joan then tried to bribe the policeman and was taken to the local Hollywood precinct. Allowed one call, she called Howard Strickling, in charge of publicity at M-G-M. Strickling called L. B. Mayer, who called his friend the chief of police (who would later be hired to head Metro's security division). Joan was released without being booked, and after Howard Strickling visited the injured young woman in the hospital, with a thousand dollars in crisp, clean bills, all claims against the star and the studio were dropped.

Joan in her first M-G-M talking film, "Untamed," November, 1929.

In September 1928 Crawford was not as fortunate in keeping the news of another indiscretion out of the tabloids. That month she was named as "the other woman" in two divorce cases. One plaintiff told the Los Angeles

Herald

that "the Venus of Hollywood" stole her husband and she was suing Crawford for damages. Another woman claimed her husband was the recipient of "expensive gifts" from Joan, and spent long weekends with her in "motels and resorts, up north." Both men, one an assistant camera-operator, the other a carpenter, were employed by M-G-M; after a consultation with their bosses, they returned to their wives, temporarily.

Joan, as a result, was called before Louis B. Mayer. She was now a star, he told her. She had responsibilities, not only to the studio, but to the hundreds of thousands of young people ("My public," said Joan) who wrote to her each week. She had a choice, Mayer went on. She could continue to burn herself out by kicking up her heels with riffraff in speakeasies and hotel rooms, or she could become a bigger star, by practicing selection and discretion in her private life and increased zeal and devotion in her professional one. "He told her she had to put a lid on it," said a Metro publicist. "If she wanted to stay at Metro, she had to behave herself, at least in public."

Joan was no fool. She knew she was the darling of the Jazz Age and that, short of murder, her young fans would forgive her anything. But she also knew this Jazz Age thing wasn't going to last forever (Black Monday was just around the corner), so with tears in her eyes she repented at the knee of the great L.B. She told Papa Mayer not only that she was going to be a good girl and a lady from that day forward, but with his blessing, she intended to become the biggest and brightest star Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer had ever produced.

With this new mantle of responsibility on her shoulders, Joan proceeded to alter her offscreen life-style drastically. She quickly dropped her old friends and made new ones, appearing in public with men, "safe types," who could help her career and contribute to her "growth as a human being." She preferred men to women, she said-"They're smarter and stronger and they seldom want to borrow your clothes." Director Edmund Goulding was the first to advise Joan to practice restraint in front of the motion-picture camera. "Hold back," he told her. "Give the audience just a taste of what you're thinking, not the full meal." (Goulding would offer the same advice to Bette Davis, who refused it, saying, "No! I

am

larger than life and that's what my public wants to

see.")

William Haines, a leading man at Metro, was said to be in love with the charming Joan, but he was "as gay as a goose" and he taught her important things like dress and diet and good posture. She gave up smoking and started chewing gum, "because I heard it was good for the jawline," and learned how to walk three Metro blocks with a brick balanced on her head. "That helped straighten my spine," she said. "It also threw back my shoulders and firmed up my ass." Paul Bern was another good friend and major influence. He was an important M-G-M producer and an intellectual. He wanted to go to bed with Joan. "He sent me a fur, a coat of ermine," she said. "I sent it back. Don't think it didn't take willpower. But I kept his friendship." Bern, who would later counsel and marry Jean Harlow, advised Crawford on what books to read and what parts to play in the future. "He recognized something in me that other men did not care to see—that I had a brain."

One night Bern escorted Joan to the theater. The play was

Young Woodley,

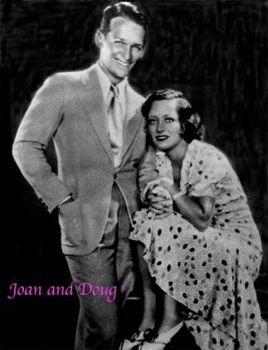

and the handsome young lead, Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., caught Joan's fancy. "He was enchanting, the epitome of suaveness," she said. She wrote him a note, asking him to call her sometime. When he called the next day, she said she was busy all week but he could come for tea on Sunday afternoon. At her request he brought along a small signed photograph. She gave him a large eleven-by-fourteen studio portrait. He thought she was "vital, energetic, very pretty," with two vocal sounds—"one resonant and professional and one more blatantly flat." Although at times "she tried too hard to be what Noel Coward called 'piss-elegant,'" it was Joan's magnetic dynamism that entranced young Doug, and her "gracefully muscled legs." She fell in love with his good looks, and his background. His father was Doug Sr., the world's favorite swashbuckler, and his stepmother was Mary Pickford, Joan's favorite childhood star and the current czarina of Hollywood society.

Doug Jr.'s talents included writing, painting, and the playing of several musical instruments. "He also had a gay delicious wit, exquisite manners, and so much knowledge," said Joan. Some suggested she was using the nineteen-year-old lad to further her own social and financial ambitions. "The money part was a joke," said a Crawford ally. "She was making more than him at the time, and, furthermore, when they met he was supporting his mother and in debt up to his elegant ears. As for the talk about her being a social climber, everyone in Hollywood at that time was trying to scale the walls of Pickfair."

When the press were alerted that the fickle, fun-loving heartbreaker Joan had finally fallen in love, America took the romance of the Charleston Queen and the Prince of Pickfair to their hearts. The daily coverage and the fan-magazine reportage reached epic proportions. "Many 'inside stories' were printed," said Doug, "some invented by studio press agents, some by gossipy friends, and some by dear self-dramatizing Billie."

"I was Billie and he was Dodo," said Joan. "We dined together, bronzed on the beach, played golf and tennis, danced Saturday nights at the Biltmore or the Palomo Tennis Club. We were in love and had a language of our own. It went something like 'Opi Lopov Yopov'—how nauseating can you get?"

Doug introduced her to culture and social graces. "I who all but ate my peas with a knife," she said. "Laughable, patent nonsense," said Doug. "She was a very experienced lady. But one with an inferiority complex, which she used as a whip to spur herself onward and upward."

"From Jazz to Gentility, Joan Crawford is going to be demure if it kills her," said writer Ruth Bren in

Motion Picture

magazine. As the romance progressed, the metamorphosis of Joan the lady became more apparent. "She spoke in a low voice," said Bren, "the raucous laughter was gone, her wardrobe leaned towards softly clinging materials, white gloves and picture hats—outfits obviously planned and more suited to the grounds of Pickfair."

But the gates to the neo-ancestral Hollywood home of Doug Sr. and Mary Pickford did not swing open for Joan Crawford. "She was gay and giddy and Pickfair did not go in for that," said one writer. "What did they think she would do," asked another, "wipe her nose on the drapes?"

The accounts of their exclusion from Pickfair were exaggerated, Doug Jr. insisted. He and Joan were never invited to any of the posh dinners, but they did attend a few screenings, one of which, when the lights came up, found the young man engaged in some heavy necking with Miss Crawford, which brought a stern rebuke from Doug Sr.

"My son's current chorus-girl fling" was how Doug Jr.'s mother described the romance, while his father felt their affair was overexploited, and that Joan was" on the toughie side."

Joan was hurt, of course. Her old image of the carefree, thoughtless flapper was a bad rap, she felt, a disguise for "a very lonely young woman." Dodo knew that. "Just the other night he said to me," said Joan to Katharine Albert for

Photoplay,

"'You know, I didn't change you, Billie. You were always like this, only nobody knew it.'"

M-G-M naturally sanctioned the romance. L. B. Mayer, pleased that "daughter Joan" was pursuing respectable pleasures, took advantage of the couple's widely publicized romance by teaming the two in a sequel to her hit picture,

Our Dancing Daughters.

The new movie was called

Our Modern Maidens,

which in turn led to

Our Blushing Brides.

("What next?

Our Ditsy Divorcees?"

asked one caustic critic.)

Upon the release of the picture, Joan announced her engagement to Doug Jr. in the social pages of the New York

Times

and the Los Angeles

Times.

The news and the proper placement, she felt, would result in an invitation to wed at the home of Doug and Mary. Their silence was cataclysmic to Joan, who realized that her dream of a white wedding on the lawns of Pickfair was not to be. So, to save face, just in case her snobbish in-laws planned on boycotting her wedding in Los Angeles ("They would cheerfully have poisoned me before I married their fair-haired boy," she said later), she and Doug decided they would elope to New York.

In late May 1929, the couple left for New York. At City Hall, to avoid the press, they ducked in a side door and applied for a marriage license. Asked for her birth certificate, which would have proved her true age, Joan swore it was lost, then pulled a letter from her handbag. It was from her mother, swearing she was born in 1908. Doug's real mother, present at City Hall, swore

her

son was born the same year, giving the minor the extra year required by law. ("Had anyone taken the trouble, they could have popped upstairs to find my birth certificate where it is still filed, showing the true year, 1909," said Doug.)

On June 3 the couple were married in the rectory of Saint Malachy's Catholic Church. At the reception afterward at the Algonquin Hotel, when the press asked if Joan intended giving up her career for marriage and motherhood, she replied, "No, fellas, not yet. I've got a studio and millions of fans to please." Those priorities were also agreeable to the happy groom.