Bette Davis (30 page)

Authors: Barbara Leaming

Tags: #Acting & Auditioning, #General, #Biography & Autobiography / General, #Biography / Autobiography, #1908-, #Actors, American, #Biography, #Davis, Bette,, #Motion picture actors and actresses, #United States, #Biography/Autobiography

Bette "cleaning up" at the home of her friend Charles Pollock in Los Angeles.

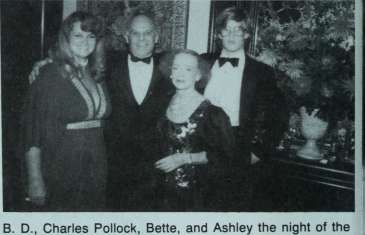

B. D., Charles Pollock, Bette, and Ashley the night of the anniversary party Bette gave for her daughter and her husband in Los Angeles in 1983. Less than a year later, B. D. began to write her devastating memoir of life with Bette, My Mother's Keeper.

Rock Hudson and Bette's son-in-law, Jeremy Hyman.

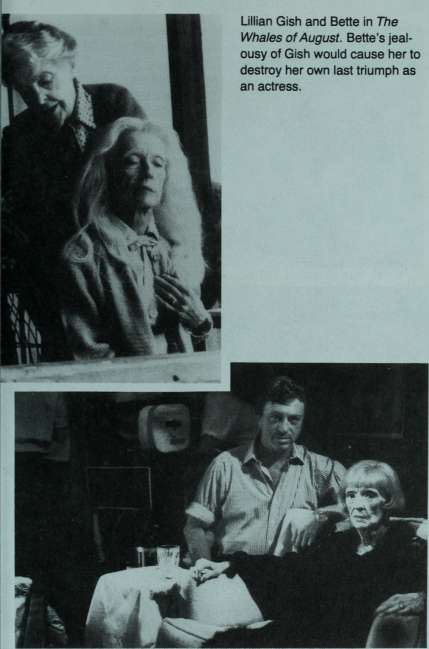

Lillian Gish and Bette in The Whales of August. Bette's jealousy of Gish would cause her to destroy her own last triumph as an actress.

Bette and director Larry Cohen on the set of her final film, Wicked Stepmother. Bette walked out on the project after she saw herself in the first rushes.

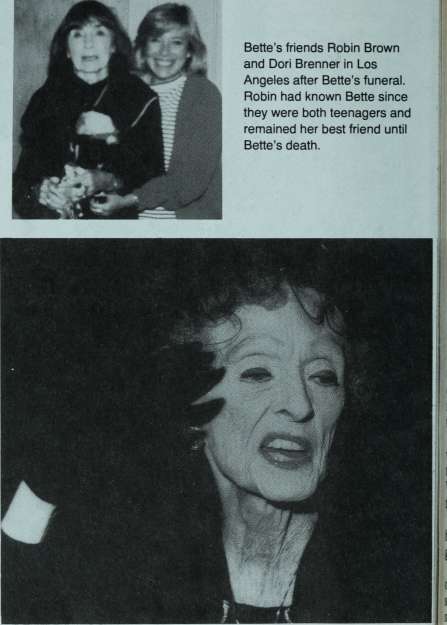

Bette's friends Robin Brown and Dori Brenner in Los Angeles after Bette's funeral. Robin had known Bette since they were both teenagers and remained her best friend until Bette's death.

Bette Davis near the end of her life. Even after cancer and several strokes she was still "Battling Bette."

while, behind her, a desperate Horace struggles to crawl upstairs for the medicine. Where Hellman's screenplay intercuts between Regina (in the living room) and Horace (on the staircase), Toland's deep-focus technique puts the two in a single intricately composed shot.

"I can have him sharp, or both of them sharp," the cameraman told Wyler, who preferred that only Regina be crisply defined in the foreground, in order that we might watch her face and body for signs of what she may be thinking and feeling as she leaves her husband to die.

Bette gets her effect by very gradually lengthening her spine, then extending the back of her neck, as, with great effort, Horace drags himself up the stairs behind her: making Regina's slow ascent in the foreground of the shot a grotesque reflection of Horace's in the rear.

And there are other fine details in Bette's performance: the sense of amplitude she projects with uplifted chest and outstretched arms; the degree of expression she places in her feet and legs, whose sudden "unladylike" extensions deftly embody her character's boldness.

Too often, however, Bette takes her details from past performances, burdening her character with what Wyler derided as meaningless and unnecessary gestures: appropriate for Julie Marsden or Leslie Crosbie, perhaps, but not for Regina Giddens, about whom they communicated nothing. Why, the director wanted to know, does Bette's Regina tug incessantly at handkerchiefs and other fabrics; why does she keep catching errant strands of hair and pulling them back from her face?

' 'What is acting, anyway?'' Wyler would ask. ' 'Are you thinking what the character is thinking or are you wondering, 'Shall I give them a bit of the old profile?' or 'Shall I wave my arm a little?' Well, you know the answer yourself. The camera catches all these things and tattles direcdy to the audience."

When these remarks appeared in the press after she and Wyler had finished their work on The Little Foxes, Bette went wild, angrily vowing never to work with the director again.

At which a gleeful Jack Warner leapt into the fray, to assure Bette of his "indignation" that Willy Wyler would dare to criticize her so. Unlike Wyler, the studio boss clearly had no objection to the star's playing "Bette Davis" on-screen, or to her repeating bits of physical business that had appealed to audiences before. In the past, Bette had repeatedly aligned herself with Wyler; now suddenly, that September of 1941, she found herself writing a note of unprec-

edented unctuousness to Jack Warner. She thanked him for taking her side against Wyler, whom she bitterly accused of having hurt her very deeply.

To which Bette would "grudgingly" reply, "All right, I'll try it. I'll look at the dailies tomorrow and see if I like it."

After the devastating collisions with Wyler during The Little Foxes, this is the film where, with her usual flair for off-screen theatrics, Bette begins to assert her dominion over directors. As if in reaction to Wyler's vexing remarks in the press (clipped from the New York World-Telegram and preserved in her album), henceforth she will stubbornly insist on elaborating her characters from the outside, rather than from within—at length, with unmistakably disastrous results as her art passes into a kind of decadence, a love of ornament and exaggeration for its own sake.

In Now, Voyager, however, the actress's emphasis on externals is dramatically effective because, in large part, those externals constitute the heart and soul of the film, which chronicles the remarkable metamorphosis of Boston Brahmin Charlotte Vale from a meek, neurotic, overweight, prematurely aged spinster to a strong, slender, attractive woman of impressive efficacy and independence. When Warners released the film in 1942, in the aftermath of America's December 1941 entry into World War II, Charlotte's transformation held a special meaning for American women, faced with the necessity of discovering their own inner strength and power. Compelled to assume the jobs and responsibilities left behind by the men who had gone off to fight, American women took immense comfort in Charlotte's message that even the meekest among them was capable of effective independent action. Significantly, Charlotte must finally learn to live without the man she loves; because Jerry Durrance is married to another, Charlotte has to find the strength to care for his daughter, Tina, on her own. Functioning bravely and forcefully in his absence, Charlotte proves her love for Jerry as she gives new meaning to her own life by accomplishing things she had never dreamed were possible. Coming as it did at that historical moment, Now, Voyager consolidated the Bette Davis image as a model of feminine power and independence: an image that, in 1942, resonated all the more strongly and importantly for American women hoping to find similar qualities in themselves while men were away at war.

Now, Voyager was Hal Wallis's first independent production at Warners under a new arrangement with the studio, so that it was only natural for him to take a special interest in the film's day-to-day progress. Interoffice memoranda show an unusually high degree of creative input from Wallis (much of it devoted to quickening the story's pace), of a sort that Wyler would scarcely have brooked but

that the more malleable and diplomatic Rapper apparently did his best to accommodate.

For her part, Bette was a good deal less flexible when Wallis called for several minutes to be reshot because he found the actress's line readings "stagey and artificial/' Davis, apparently overwhelmed by fear, is recorded to have been stricken with laryngitis—almost certainly hysterical in origin—which held up the production for several days.

It was evident that Bette wanted to run the show, and the director was constandy put in the unenviable position of having tactfully to relay Wallis's "constructive criticisms" of her performance, or of other aspects of the production, without rousing her ire. The production head shrewdly steered clear of the set and "Queen Bette," as they called her.

Unit manager Al Alleborn's notes show that another drag on the production was caused by Gladys Cooper, cast in the role of Charlotte's domineering mother. The actress, who had played Leslie Crosbie in the London premiere of The Letter, repeatedly forgot her lines or botched her dialogue.

But mosdy the problem was Bette—as Rapper declared in answer to two curt letters of complaint from Jack Warner when the production fell seven, then nine days behind schedule. Warner wrote to Rapper: "I want to impress upon you that unless there is a marked improvement, I must seriously consider the pictures you will do in the future." "Above all," wrote Rapper in response, "Miss Davis is a very slow and analytical lady whose behaviour had to be treated with directorial care and delicacy. Believe me, that in itself is a full day's work."

"Cut!" cried Rapper, at the close of a scene in which, costumed and made up as a homely old maid, Bette bursts into uncontrollable tears: a signal to the psychiatrist Dr. Jaquith (Claude Rains) that Chariotte is on the verge of a nervous breakdown. (Wallis, it should be noted, had ruled against the original monstrous makeup Davis and Perc Westmore had devised for the spinster Charlotte: a fantastically ugly face that struck the appalled production head as overwrought and self-conscious.) Bette had been sobbing, with tears streaming down her cheeks. Suddenly she turned it off, flashed a big smile at the crew, and shouted lustily, "How'd I do, boys?" Then, abrupdy shifting gears again, a grim-faced Bette headed toward her dressing room as she snapped "Come on!" at Bobby. Day after day, Bobby haunted the set of Now, Voyager, silendy watching her sister from the sidelines.

"Bette was one of the strongest and most determined women

I've ever met, and the sister was one of the weakest," says Meta Carpenter. Painfully aware of Bobby's history of mental illness, studio workers did what they could to be kind to her, especially in light of Bette's brusque treatment: behavior that led Carpenter and others to speculate about the extent to which Bette might actually have been responsible for some of Bobby's breakdowns.

Davis and the script supervisor became better acquainted when the company moved to Lake Arrowhead for location shooting. After the day's work was done, the two women would take long walks together, during which Bette indulged in what Carpenter describes as "gill talk" about her marriage to Ham Nelson. But the more Bette talked, the more it struck her companion that, by this point, nothing was really meaningful or important to Davis except her work. "I don't think Bette was really capable of any great emotional depth or feeling,'' says Carpenter, with evident sadness.' 'Her whole life was her career."

1 'Bette Davis advises that she expects to be paid during the two weeks she devotes her time to the Bond Drive," wrote Roy Obringer to Colonel Jack Warner, on August 13, 1942. "There appears to be no chance of changing her mind on this, as she even went so far as to state that if there were any question, it had better be settled before any publicity broke relative to her going on the drive."

America was at war by now, which might have put into perspective Bette's perpetual, increasingly irrational skirmishes with directors and with her studio. But as Obringer's detailed report to Warner makes clear, when, like a great many other Hollywood personalities, Davis found herself recruited to participate in the War Bond Drive while she was between pictures, as if by reflex she promptly went to war with Warner, demanding that he pay her for her time.

Bette made up for everything, however, through her efforts as president of the Hollywood Canteen on Cahuenga Boulevard in Los Angeles, where American servicemen waiting to be shipped out to the Pacific mingled with their favorite Hollywood stars.

In her photograph albums one discovers numerous images of the actress posed with an endless succession of servicemen at the canteen. In a hurry to get through these bland, repetitious photographs, one might easily pass over several singularly odd shots hidden among them: eight-by-ten blowups of images taken at a considerable distance, presumably from across the former livery stable that Bette had leased to house the Hollywood Canteen, with funds raised by her agent, MCA president Jules Stein. Unlike her other mementos of die canteen, these photographs do not contain Bette, leading

one to believe that she might have taken them—but why? of whom? Only on close inspection does one make out the scarcely recognizable face of William Wyler, repeatedly photographed unawares in his air force uniform, as he prepares to go overseas.

"The Red Cross has nothing to do with Warner Bros.," scribbled Jack Warner, nervously drafting a March 15, 1943, telegram to Bette, who—on holiday at the Hotel Los Galmingos in Acapulco, Mexico, after completing the film Old Acquaintance—had angrily refused to appear at an upcoming reception to launch the Mexican Red Cross. She felt that the studio should pay her to attend

The invitation to Davis had been part of a concerted government effort to strengthen inter-American relations by building up cultural ties. In hopes of countering the Axis countries' antidemocratic propaganda, the United States government regularly invited Hollywood personalities to serve as goodwill ambassadors in Latin America: hence the potential embarrassment to the Roosevelt administration when Bette Davis turned down the Mexican president's invitation to the charity function.

Drafting an answer to Bette's furious telegram accusing the studio of once again trying to dupe her into working for free, Jack Warner began with the sentence about the Red Cross having nothing to do with Warner Bros., then, as his draft notes show, crossed it out. He probably feared that too direct a response to her charges would only set her off again.

Next Warner tried a sentence about being "rather astonished" by her angry wire; but he crossed that out as well, replacing it with the less inflammatory "read your wire."

' 'We are all trying to do everything in our power to cement inter-American relations and assist our sister republic Mexico in launching its Red Cross with this event at which the president of Mexico will take time out twice to meet group," Warner continued, anxious to explain why it was important for Bette to attend.

He went on to remind her that "there is a war on and it's more important than Warner Bros., you, me, or any other individual"— but this, too, he scratched out, presumably because it might further provoke her: the last thing he wanted to do under the circumstances.

By this point, evidently, Jack Warner had taken to dealing with Bette as gingerly as her mother always had: anticipating the inevitable explosions, humoring her when they occurred, meanwhile doing everything possible to avoid setting her off anew. However, he seemed not to have comprehended the particular configuration of events that had sent her over the edge in Mexico.

After playing a secondary role in director Herman Shumlin's film version of Lillian Hellman's Watch on the Rhine, Bette undertook preparations for her next star vehicle, Old Acquaintance, to be directed by Edmund Goulding. She had been allowed to ride roughshod over Irving Rapper while filming Now, Voyager, and during preparations for Old Acquaintance Bette had expected to do the same with the infinitely less tolerant Edmund Goulding. Finally, Goulding issued Jack Warner an ultimatum—"Either I am working for Warner Bros, or Miss Davis and there is a difference." Before a choice was made, Goulding suffered a massive heart attack and was replaced by thirty-six-year-old Vincent Sherman.

"I was just a beginning director at that time," says Sherman. "Bette was a big star, who had won two Academy Awards. She was far above me, not just in standing at the studio but in terms of salary." Before long, the young director appeared to make a momentous decision about how to deal with his persistently out-of-control leading lady. "He went and slept with her," recalls Meta Carpenter. "After that, the next morning she was an angel. She came on the set a changed person." On several occasions, when shooting was finished for the day, Carpenter found herself asked to stay late while Bette and her director were alone together in her dressing room. Ordinarily, the couple would invite Carpenter in for a drink afterward. One night, however, while the script supervisor was reluctantly standing guard, Farney appeared at the gate, in search of his wife. When Carpenter informed Bette, the enraged actress sent word that her husband was not to be admitted to the studio grounds.