Between Giants (4 page)

Authors: Prit Buttar

Tags: #Between Giants: The Battle for the Baltics in World War II

In March 1918, following the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, Germany announced that it recognised Lithuanian independence on the terms that the Vilnius Council had announced on 11 December. Wrangling over the precise nature of this independence continued, and in June, the council invited the Count of Württemberg to become monarch of Lithuania. This placed an intolerable strain on the council, and several members resigned. In any event, the German government refused to accept this arrangement, and prevented the would-be King Mindaugas II from travelling to his new country.

11

The frustrated members of the Vilnius Council found that Germany blocked almost every attempt they made to formulate policy, a deadlock that continued until the collapse of Germany in November. At this stage, the council revoked its invitation to the Count of Württemberg. It also expanded its membership to include Jewish and Belarusian members, in an attempt to increase its popular appeal with these two communities; at first, the Jewish community was offered two seats, but this was declined, with the Jewish leaders demanding that their membership should be proportional to the Jewish population within Lithuania. Consequently, they were offered a third seat. A new Lithuanian government was proclaimed, with Augustinas Voldemaras as prime minister. Antanas Smetona, who had chaired the council when it first formed, became President.

Lithuania found itself in a chaotic state. Groups of German soldiers, often refusing to follow the orders of their officers, crossed the country in a steady stream towards Germany. The new government had no means of collecting taxes, and consequently was unable to carry out any significant functions. Voldemaras announced that Lithuania did not intend to threaten its neighbours, and therefore concluded that there was no urgency to create an army. Unfortunately for Voldemaras, the Bolsheviks had a very different attitude, and swiftly overran the eastern parts of Lithuania. On 5 January 1919, they reached Vilnius.

The historical capital of Lithuania was a multi-ethnic city. A German census in 1916 suggested that half of the city’s population was Polish, and a substantial part of the remaining population was Jewish, leaving the Lithuanians in a very small minority; however, other surveys suggested that the population of the surrounding area was predominantly Lithuanian.

12

Indeed, the Jewish population of Vilnius had earned the city the appellation of the ‘Jerusalem of the North’ from Napoleon. Such a multi-ethnic mix was bound to create additional tensions, which could be exploited by any outside power that chose to do so. Belatedly, the Lithuanian nationalist government started to raise troops, but these were in no position, either tactically or in terms of their strength, to defend Vilnius; the most active defenders were pro-Polish partisans, but they were unable to prevent the Red Army from seizing the city. From here, the Bolshevik troops gradually advanced west, but their drive ran out of momentum as their almost non-existent supply lines failed to replenish the troops. The Lithuanians had also succeeded in raising German volunteers to fight for them, particularly in Saxony, and these veteran soldiers proved to be a formidable force.

Another army that was operating in the area was that of Poland. Already at war with Russia, the Poles launched a major offensive against the Red Army in the spring of 1919. Józef Piłsudski, the Polish head of state, planned the operation with his customary meticulous attention to detail, launching diversionary attacks on Lida, Navahrudak and Baranovichi. His main objective, though, was Vilnius, with a force of 800 cavalry, 2,500 infantry and artillery assigned to the task. Rather than wait for the slower infantry to arrive, the Polish cavalry commander, Colonel Wladyslaw Belina-Prazmowski, decided to attack with his horsemen on 18 April. He swept around the city and attacked from the east, taking the Soviet garrison by surprise and overrunning the suburbs. As the Bolshevik forces rallied, the Polish infantry began to arrive, and with their support – and aided by Polish partisans from Vilnius – Belina slowly gained the upper hand, clearing the city of Russian forces by the end of 21 April.

13

By the end of June, the Red Army had been driven out of almost all of Lithuania, and negotiations now began about the border between Poland and Lithuania. This proved to be a difficult business, not least because Piłsudski did not wish to see the creation of an independent Lithuania, favouring the restoration of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Deadlocked over the future status of the Vilnius region – claimed by both countries, but occupied by Polish troops – the Lithuanians and Poles asked the Conference of Ambassadors of the Entente Powers to intervene. At this stage, the difference in diplomatic status between Lithuania and Poland became starkly apparent. Poland had been recognised by the Entente Powers, and was even specifically mentioned in one of Woodrow Wilson’s famous Fourteen Points:

An independent Polish state should be erected which should include the territories inhabited by indisputably Polish populations, which should be assured a free and secure access to the sea, and whose political and economic independence and territorial integrity should be guaranteed by international covenant.

14

By contrast, Lithuania had not yet received international recognition. In many circles, particularly those that favoured a restoration of the Russian Empire, Lithuania’s independence was distinctly unwelcome. It can therefore have been of little surprise to anyone when the Conference of Ambassadors chose not to return Vilnius and the surrounding area to Lithuania.

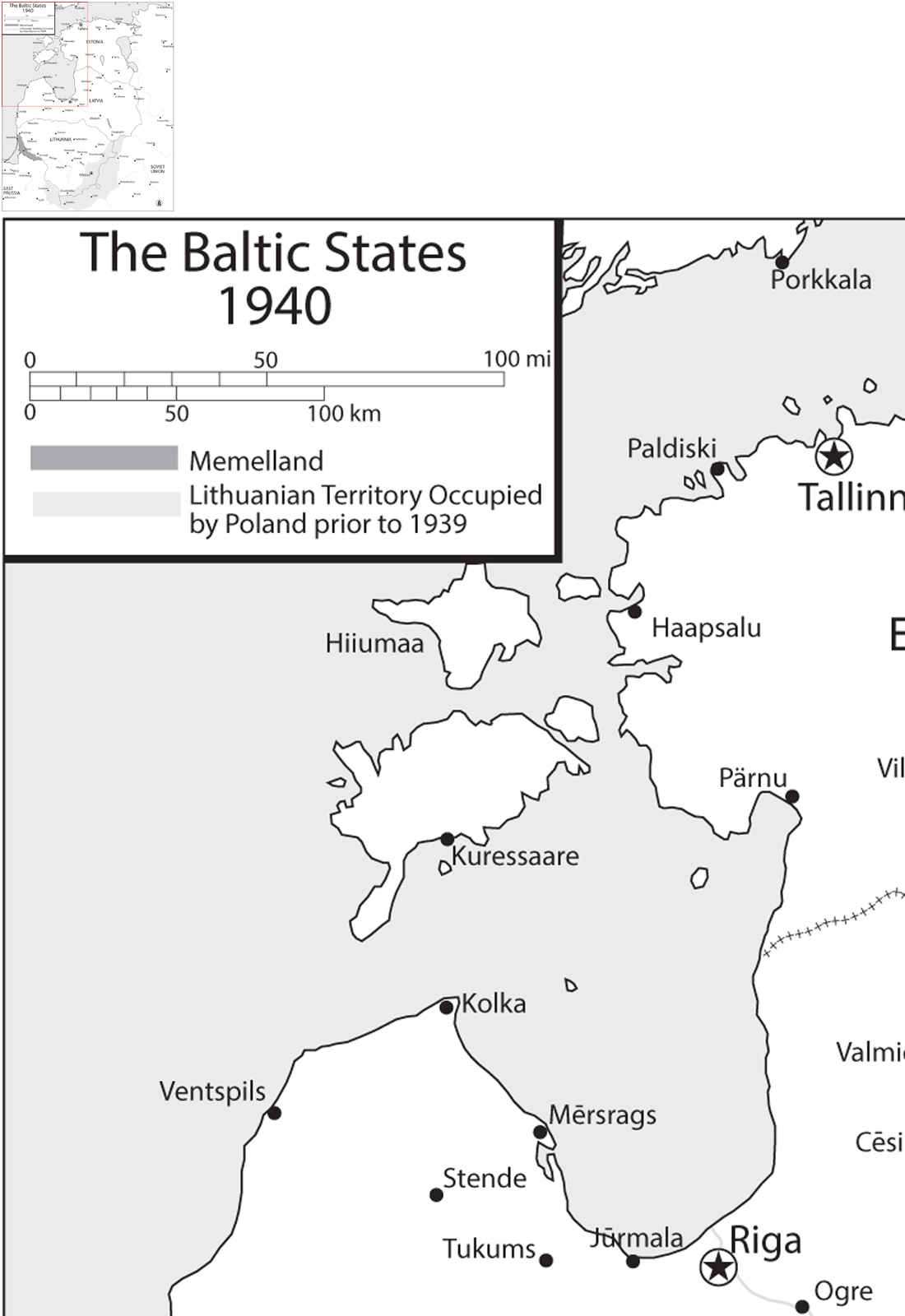

Although he was opposed to Lithuanian independence, Piłsudski was acutely aware that any future commonwealth could only succeed with the agreement of the Lithuanian people, and he made every effort to persuade the Lithuanians to cooperate with his plans. He and his subordinates proposed that the fate of the Vilnius region be decided in a plebiscite, but the Lithuanians rejected this. But the Bolsheviks were not quite finished. In 1920, a revitalised Red Army once more invaded, driving the Poles out of Vilnius. Shortly after, Soviet Russia and Lithuania agreed a peace treaty, as part of which the Vilnius region was assigned to Lithuania. Such an arrangement was unacceptable to the Poles, and in October the Polish general Lucjan Żeligowski apparently mutinied and marched on Vilnius, taking the city on 9 October. He then declared the creation of the Republic of Central Lithuania, which merged with Poland in 1923. It later transpired that Żeligowski’s mutiny was nothing of the sort, and had actually been ordered by the Polish head of state, Piłsudski. Vastly outnumbered, the Lithuanian army could do nothing to counter this seizure of the region, and the Vilnius question remained a source of severe friction between the two countries throughout the inter-war years, preventing any possible cooperation between Poland and Lithuania. The Baltic wars of independence were therefore a manifestation of the conflict between two alternative visions: on the one hand, the three states had strong nationalist aspirations, while on the other hand, their more powerful neighbours – Soviet Russia, Germany and even Poland – regarded them as too small and weak to survive without being part of a larger power bloc. This question would be subjected to even more brutal inspection in the Second World War, and the resolution of the issue would take over 70 years and cost millions of lives before independence was finally achieved towards the end of the century.

MOLOTOV, RIBBENTROP AND THE FIRST SOVIET OCCUPATION

The decade that preceded the Second World War saw major changes in all three Baltic States. Originally created as republics, they all adopted totalitarian rule. Estonia’s head of state, Konstantin Päts, used a threatened coup by hard-line anti-Soviet and anti-parliamentary nationalists to declare rule by decree in 1934. In the same year, the Latvian leader, Kārlis Ulmanis, also dismissed his parliament, partly as a response to the worldwide economic situation. In the case of Lithuania, a military coup in 1926 – triggered by growing criticism of the government for its attempts to negotiate with the Soviet Union – abolished parliament and placed Antanas Smetona in command of the country. It is noteworthy that in all three cases, a powerful motivation behind the unrest that led directly or indirectly to dictatorship was growing anti-Bolshevik sentiment. Much of this was due to persisting concerns that the Soviet Union might one day attempt to restore Russian control of the region. At the same time, resentment at German attempts to establish hegemony in the region in the aftermath of the First World War remained strong. Consequently, the people of the Baltic States, and their leaders, watched developments between their powerful neighbours with concern. The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, announced on the eve of the German invasion of Poland in 1939, came as a shock to the Western Powers, and an even greater shock to the Baltic States, appearing to confirm that neither neighbour was remotely interested in the ongoing independence of the three nations. But the background to the Pact was that despite their dramatic ideological differences, the two nations had attempted to define non-aggression treaties for many years.

In the aftermath of the First World War, Weimar Germany signed two treaties with the Soviet Union. The first was the Treaty of Rapallo in 1922, in which the two powers renounced any territorial or financial claims against each other. This was followed four years later by the Treaty of Berlin, which declared a five-year pact of non-aggression, and neutrality by either power should the other be involved in a conflict. In 1931, an extension to the latter treaty was agreed, but almost immediately relations between the two countries deteriorated, a process that accelerated after Hitler came to power in 1933. Persecution of the German Communist Party, overt hostility in diplomatic arenas and the publication of the second volume of

Mein Kampf

, calling for German expansion into Russian territory and equating communists with Jews, all played a part.

Maxim Maximovich Litvinov, the Soviet Commissar for Foreign Affairs for most of the 1930s, regarded Nazi Germany as the greatest threat to the Soviet Union. His preferred policy to contain the German threat was to build strong links with France and Britain, but Stalin’s insistence that any such alliance had to include the right of the Soviet Union to station troops in Estonia and Latvia made agreement almost impossible, given the role that France and Britain had played in helping Estonia drive the Red Army from its territory during the wars of independence. For Stalin, the proximity of the border between the Soviet Union and the Baltic States – particularly Estonia – and key locations, such as Leningrad, made a Soviet military presence in the three states a defensive necessity. In 1936, the NKVD (

Narodnyy Komissariat Vnutrennikh Del

or ‘People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs’, the Soviet Secret Police) reported that there were growing links between many Estonian government officials and Germany. In addition, the NKVD report continued, the Estonian government believed that the Latvians were already ‘completely in the service of Germany’. By contrast, the ordinary people of the two countries were reported to be pro-Soviet.

1