Beyond Belief (27 page)

Authors: Jenna Miscavige Hill

“But how do you

know

?” he asked.

“I just do,” I replied authoritatively.

But the truth was, I really didn’t know. This was what I had been told since my earliest childhood, and I believed it; however, I couldn’t say why I believed it. I’d never thought of myself as just a body. I’d never thought of myself as

just a piece of meat

, the phrase Scientologists always used to refer to the human body. The idea that Martino believed differently made me think about the whole concept of a Thetan with a scrutiny that felt foreign.

Other times, we found ourselves talking about Scientology’s most precious secret—the OT Levels. Because Flag was one of the few bases where the higher OT Levels could be administered, there was an air of secrecy about them everywhere. Frequently, the higher ups briefed the staff about the increased security around the OT Levels, taking pride in the fact that the levels were safer than ever. They’d make announcements listing out the various measures that had been taken to make the delivery of the OT Levels completely secure—some parts of the base that dealt with the OT Levels were only accessible through a combination lock and special key card, and there were other special security measures as well.

Not surprisingly, all of this secrecy only made me more curious about the levels themselves and the secrets that they held. I can’t say whether it was deliberate strategy by the Church, but the end result of this security talk was a powerful desire to learn the truth. I couldn’t wait to climb the Bridge and find out what the OT Levels were. I figured they had something to do with how we all came to exist, which was something I often wondered about. Occasionally, I’d try to get the librarian to reveal information about the levels to me or at least hint at it, but not surprisingly she refused. She knew as well as I did that there was a risk I could be physically harmed if I learned the levels out of order.

Compelled as I was by the mystery of the levels themselves, this concept of physical harm also perplexed me. Talking all this over with Martino, I kept coming back to this simple question: how can information hurt you physically? It made sense that information could upset you emotionally—but physical harm was a different story. I tried to imagine what that harm would be. Something about the whole idea seemed wrong, but the threat of pain and even death inspired fear nonetheless.

My discussions with Martino always possessed an openness that I hadn’t encountered before; they weren’t regimented or scripted, they just sort of unfolded depending on how comfortable we were and what we felt like sharing. It wasn’t long before I confided in him that my mom was in trouble and on the RPF. As I told him the story of what had happened, he was visibly moved by my words. From then on, he would always ask for updates about my mother, often becoming as excited as I did when a letter from my mother arrived. Since Mr. Rathbun always kept the letters, I could never show them to him, but he was enthusiastic about them nonetheless.

More than anything, it was this sincere concern that made me feel more comfortable with the skepticism he displayed about the Church. Because he was so good-natured, I could see that it didn’t come from some sinister desire to be troublesome or get me in trouble. He wasn’t a bad person and he wasn’t trying to undermine the entire Church. He was just trying to understand the world he had grown up in, and in doing so, was asking some uncomfortable questions.

It wasn’t just Martino’s earnest approach that opened me up to these ideas; after everything I’d been through with Justin’s departure and my mom almost leaving the church, I was also at a point where I’d started to acknowledge that plenty of people, including those I cared about most, had these kinds of thoughts. If I’d met Martino just a year earlier, I probably would have dismissed his questions as invasive and dangerous. Now, in part because of what had happened to Justin, I found his preoccupations becoming my own.

It wasn’t one big issue he raised, just a lot of little ones. Why had I been separated from my parents? What did these courses really mean? Why did we all have to work as we did? What does it really mean to be a Thetan? It was a lot to take in, but it was also energizing to think about these issues in such a different way. Of course, the tricky thing about these little questions was that, once I started asking them, it was hard to stop.

A

FTER A FEW MONTHS,

M

ARTINO WAS BY FAR THE BEST FRIEND

I had. He knew everything about me, and I about him. He understood things in a way that my friends in CMO didn’t. Now they all seemed so fake and so robotic. I became friends with his friends. Tyler was in that group. He was cute, a goofball, and a good friend, but by now I’d fallen for Martino. The best part was that he clearly felt the same way about me.

The only problem was that because he wasn’t in the Sea Org, he and I weren’t supposed to even talk outside the course room, so we had to do our best not to let others know what was going on. Neither of us let the fact that we were not supposed to speak get in the way of our friendship, but it certainly complicated life. Being friends with Martino made it much harder to relate to other people in the CMO. People in the CMO didn’t think like he did and didn’t have discussions in the same way. It was hard to go from being open and honest to stifling everything. This was especially true with Olivia and Julia, with whom I worked.

They’d always been intense about their work, but, after I began to spend time with Martino, I started to see they weren’t just intense; they used the power of their positions to intimidate the rest of the group. The policies for our department instructed that we were supposed to

help

people do their jobs—help them find a disturbance or down statistic in any part of the organization, investigate that disturbance, and root out anyone who was causing it. Instead, Julia, in particular, became obsessed with enforcing the rules and checking people’s mail, and Olivia often went along with her although I could tell her heart wasn’t really in it. They would walk around with swagger sticks—sticks carried by Sea Org members to add an authoritative presence—which they would slam on someone’s desk if that person was resistant when asked to show his daily statistic graph. Julia would yell at anyone whose statistics were down, leading many people, including myself, to falsely report their statistics. If you were found to have done this, of course, you would get into even more trouble and be assigned to a lower condition. People who flunked meter checks would be put into a metered ethics interview, during which Julia would yell at them to come clean with their transgressions, while she loomed behind the E-Meter operator.

Around this time, members of the CMO staff were chastised in front of the entire group for going to the canteen at night and fraternizing with Flag staff. Some were brought up in front of the group for daring to wear tank tops, which were considered too skimpy. The CMO group as a whole was put in a condition of “Danger,” and movies, outings, and libs were canceled until that changed.

Prior to that, my libs day had been a cherished part of my schedule. I only had one or two a month, and I would usually spend them with my dad’s mother, Grandma Loretta, or his sister, my aunt Denise. They were the only family I had in Clearwater, and they would bring me shopping, buy me what I needed, and take me out to eat. Sometimes, we went to the beach, and I would hang out with my cousins, Taylor and Whitney. I’d see my cousins when they came to the base for courses. Because they were all public Scientologists, not Sea Org members, their lives seemed amazing and fun.

It was awkward that I could not tell them that Mom was on the RPF. In retrospect, I wish I had. They were the few actual support people I had, and they would have given me the help I needed. However, Mom had been a top executive at Flag, so telling them would have been seen as “out PR” for Flag, Int, and my family name, even though they were Miscaviges, too. When it came to matters of ethics for Sea Org members, it was not the business of people in lower orgs or outside the Sea Org to know about them. Mom’s case was even more classified, because she was David Miscavige’s sister-in-law.

The risk of embarrassing people and my family was too great and I was afraid of the consequences, but I should have trusted my grandma. She was very human—probably one of the most compassionate people I knew. There were a few times when I was on libs that she had broken down and told me that she wished she could see my dad more. He was at Int and rarely had time off. She also complained about Aunt Shelly, who had made my cousin Whitney cry by criticizing her because Whitney wasn’t in the Sea Org.

It wasn’t just Aunt Shelly who Grandma Loretta had a problem with. She didn’t understand some of her son’s own rules. A medical nurse by training, she didn’t like the fact that the local RTC Reps oversaw her exercise program, and she couldn’t understand why she wasn’t allowed to be a nurse herself. According to her, Uncle Dave didn’t allow it, but I had no idea why it wasn’t allowed or if it was even true. I assumed that Uncle Dave didn’t want his mother working as a nurse because the medicine field was looked down upon for often prescribing drugs. Nursing work was also an admission of the power of the body. Regardless, I didn’t ask questions, because the stakes were too high. Delving into Grandma Loretta’s disagreements with my uncle could put me in dangerous territory, and I might be questioned as to why I didn’t defend Scientology’s leader, who was so hardworking and doing so much for us. I sympathized with her, though, since there were so many things I too had to give up because of my Miscavige name.

Instead of being a nurse, Grandma worked as an assistant/bookkeeper for Greta Van Susteren, the Fox TV anchor, and her lawyer husband, John Coale, both public Scientologists. Not being allowed to watch television, I had no idea who they were, but on some of my libs days, I’d go to their beach house. It was gorgeous, right on the ocean, three stories high, with an elevator. They also had a yacht, which I went out on a few times. They were both very nice to me. John was sarcastic and self-deprecating, like my grandma. Greta was tougher and hard-nosed, somewhat like my Aunt Shelly.

While not having libs days was hard, my grandmother was in the same course room with me, so I would get to see her and chat with her throughout the day. My friends met her, too, and we would all joke around together before class. I could tell that Grandma really enjoyed it. She was happy knowing that I had friends, as it provided a degree of normalcy in my life. Because she was a public Scientologist, normal was actually something that mattered to her.

Looking back, I think that’s one of the reasons why my libs days with her meant so much to me: She showed me that there was this other existence outside the walls of the Sea Org. She showed me that while people like Olivia and Julia and Mr. Anne Rathbun became obsessed with the implementations of rules and punishments, there was a way to be a Scientologist without having to have so much responsibility. For all Loretta’s belief, and the fact that her son was in charge of the entire Church, she’d managed to keep her feet on the ground throughout her life.

Unlike other people in the Church, she didn’t take herself so seriously, a quality I loved about her, and one that I saw and admired in Martino.

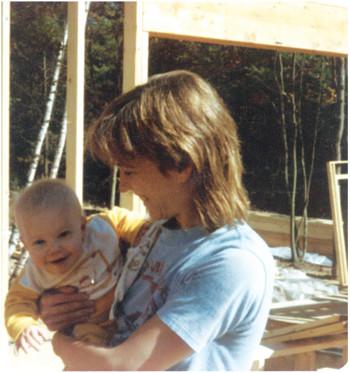

I’m less than a year old in this photograph of my mother and me in New Hampshire. Behind us are the beginnings of the dream house my parents were building.

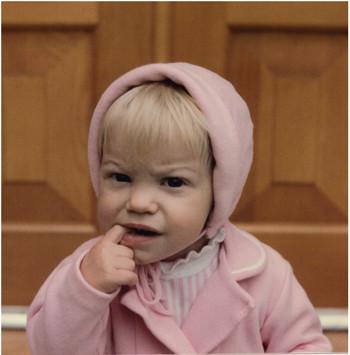

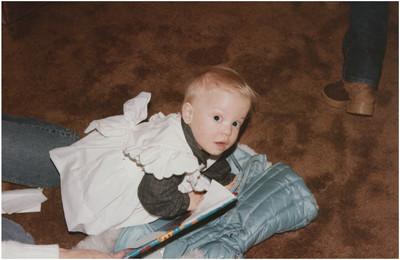

This is from my first Christmas. I can’t believe how much I looked like my own daughter does now.