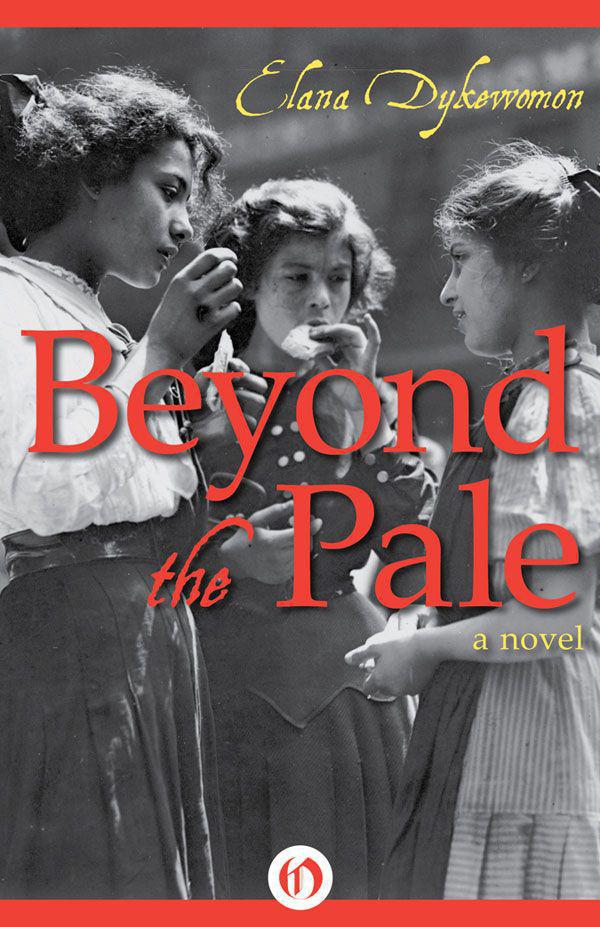

Beyond the Pale: A Novel

PRAISE FOR

BEYOND THE PALE

“One of the most compelling novels I have ever read … a work of remarkable importance.”

—Village Voice

“Sensuous, moving, inspring,

Beyond the Pale

is a wonderful novel.” —Sarah Waters, author of

Fingersmith

“Truly great novels aren’t written very often, but

Beyond the Pale

deserves all the glowing adjectives available … filled with memorable scenes and glorious characters.”

—Bay Area Reporter

“A wonderful novel … I wept like a fool for pages; these characters had become so strongly defined, I too felt like family.”

—Columbia: A Journal of Literature and Art

“Skillfully interweaves historical details—from the conditions of life in Eastern Europe’s ‘Pale of Settlement’ to the mechanics of early printing presses … [A] moving chronicle.”

—Publishers Weekly

“A page-turner that brings to life turn-of-the-century New York’s Lower East Side, with its teeming crowds, its sweatshops, the Henry Street Settlement House, and events like the Triangle Shirtwaist Company fire … Recommended for all collections”

—Library Journal

Beyond the Pale

Elana Dykewomon

Contents

The Needle Goes In, The Needle Goes Out

If We Were Really Free to Choose

For my mother, Rachel

Preface

Welcome to the new e-book edition of

Beyond the Pale

! Sixteen years after its appearance, my hope is that the digital age will introduce this book to new readers and keep it in circulation. Books are remembered by word of mouth—talk and write about the works you want to keep alive. (The

Preface

below is the one that appeared in the 2003 Raincoast edition, and best represents my process and responses to readers’ questions.)

In the three years following the publication of the first edition of

Beyond the Pale

in 1997, I gave over fifty readings. These included a 14-city tour in Germany, Belgium and England after the German and British editions were published. Many of the audience’s questions surprised me. For instance, in Germany I was almost always asked if I was a Jew. I came to interpret this as a query about whether

Beyond the Pale

was authentic, in the voice of a “real” Jew. If I wasn’t the first Jew many of these Germans had met, I was certainly the first whom they could question. To some audiences, it was a revelation that a Jew could be a secular radical lesbian; for other audiences, the revelation was that a secular radical lesbian would want to write historical Jewish fiction. Discussion periods like these give us opportunities to interrogate the text in ways that bridge cultures and build communities, which is my ambition as a cultural worker. In this preface, I’ll address the most-asked questions—but if you catch me at a reading, feel free to ask anything.

Sometimes I date the starting point of

Beyond the Pale

to 1975, when I “heard” a woman sing. She sang her life as a Jewish immigrant, a single woman coming alone to America. This song came in through the window of the third floor tenement in Northampton, Massachusetts, where I then lived—I wrote down the song and forgot about it. Then, in 1987, I “received” a poem in the voice of that same woman. She was now traveling west on a train, struggling with her grief (the poem eventually turned into the journal entry on the next-to-last page of the novel). Writers occasionally admit to hearing voices, but likely you also hear them: your mother’s voice, or a schoolteacher from childhood or, in the quiet moments before or after sleep, a few lines from a song you can’t quite place. When I was lucky enough to have the moments of receptivity that became this book, it was because my ear was pressed against the howling wind of the early 20th century. I listened. And I began to transmit what I heard.

If I had known how much work this book was going to entail (ten years!), I might never have started. But I wanted to know: Who was the singing woman? In her song and poem, she had told me about her life as a young adult, but I didn’t know where she came from. So I went to the Berkeley Public Library and started to read books about Russia at the turn of the century (those books are now relegated to a library warehouse where writers like me, trying to follow hunches, will probably never come across them). My partner Susan, a librarian, helped me by recovering books from library basements; friends gave me other leads. In hundred-year-old books I found clues about the quality, the dailyness, of Russian anti-Semitism. As I read, I realized the woman who was crooning in my ear had come from Kishinev.

Research gave me a genealogy for my character, whom I named Chava Meyer, and I started to write her life. When I began, I was aware that I was using this “voice” to engage my own grief over the loss of a lover, and later in the process, the death of my father; it is possible for writers to work on four or seven levels at once. My personal losses made me long to understand how people survive the wrenching, catastrophic events that litter history—how they are once again able to play gin rummy or offer a cup of tea to a stranger. And alongside the “big” events is the grinding quality of repressive systems. The Jews of Russia lived under a brutal form of apartheid, their every move regulated by anti-Jewish laws that were enforced with periodic violence. How can we imagine that life? I wanted to avoid romanticizing my characters, making them quaint stick figures or the cold heroes of social realism. As I worked through these problems, a larger theme emerged: I realized I was writing about a sense of community among women.

Many immigrant stories have been written by immigrants themselves and by their progeny, who recorded family anecdotes and triumphs over adversity. I read many such stories while doing the research for this book. The difference between a memoir and a novel, in this respect, is that a memoir has one hero while a novel—this novel, at least—tries to provide readers with many kinds of women with whom they might identify.

Beyond the Pale

attempts to show that, while stories must be told from specific points of view, the story of one woman is linked, is made possible, by the stories of others.

When I was a young lesbian activist in the 1970s, I looked around and saw many Jewish women working for social change—far out of proportion to our statistical probability. As I wrote this book, I realized I was writing our ancestors into being: the documented ones, those Progressive Era settlement-house and labor visionaries; and the imagined ones, the women who left no record. All these women fought for sexual, economic and racial justice before we were born. My generation did not spring full-blown from the intellectual head of 1960s civil rights and anti-war movements, as is often claimed (and as important as those movements were to our moral development). We are the bodies of hope, of women’s possibility. We are resilient, coming to life generation after generation, because the ways we love each other, the ways we love life, are impossible to repress for long. We are literally re-generation.

I also wanted to better understand my identity as a secular Jew. So, in addition to focusing on women, I set out to recover those parts of Jewish tradition that give me strength and encouragement—social activism, a sense of humor, the pleasures of scholarship, the ability to adapt while holding on to core values, the patience to take the long view of history. Of course, being a Jew also involves coming to grips with why many people hate you, and hated your great-grandparents. In

Beyond the Pale

, I worked to expose the length and breadth of anti-Jewish sentiment, without referencing the Holocaust. My intention was to show that the Holocaust was one manifestation of a worldwide system of bigotry. Wherever a stateless people exists—whether they are lesbians, diaspora Jews, Palestinians, immigrant populations of any kind or indigenous people who have been conquered or displaced—these people are made “other” by the institutions, the men, in power. The difference between communities of people who have a common interest in each other’s welfare and “the state” is not simply one of scale. It is the difference between creating a power everyone shares and a system of power over others.

I used to think we lived in the most advanced age—that our politics and “raised consciousness” were the pinnacle of human evolution. Writing this book taught me that this is not true. History is cyclical. The women of the Progressive Era were as politically sophisticated and effective as we have ever been. And the times they lived in offered more opportunities for radical analysis, for engaging institutions head-on. I envy them their strikes on every street corner, their late night debates on the merits of socialism over anarcho-syndicalism, their passion.

But passion does not get used up. It lives within us and expresses itself in many forms. At the beginning of the 21st century, as at the beginning of the 20th, millions around the world are putting their ideals into action. And women continue to form the word “peace” in our mouths like a kiss. Those kisses might still change our destiny.

The women in these pages may not have always felt that joy was their companion in struggle, but I have come to experience joy in seeing how their visions persist. May the next cycle bring us closer to them again.

—Elana Dykewomon,

2003 and 2013

Part One

A Tiny Shofar

I am original alphabet.

Letters unfurl

from my spine

cutting ciphers in

my mother’s cells.

I scan my fate

on the wrinkled walls

of that first room

clenching

in my red fist

scraps of prophecy.

I

N

K

ISHINEV THE

R

IVER

Byk is frozen. The oven is stuffed with coal, yet Miriam lies shivering on a small bed in one of the few stone houses on Gostinaya Street, cursing the walls: “Everything is ripped out. Stone—why did you let yourself be cut off the mountain, for what? I can’t, I can not go through this again. Stone—”

Gutke pulls Miriam’s dark, damp hair back, ties and tucks it behind her neck. Her fingertips push into the soft furrows of Miriam’s forehead, as if she could smooth the strain away. One of Gutke’s eyes is as black as Miriam’s, the other flecked gold. Miriam stares into one eye and then the other, working out a puzzle, letting the midwife’s gaze travel inside her, all the way to the second heartbeat. Her breathing calms.

Gutke pours wine from a jar onto a rag and runs it over Miriam’s lips. “Go on, say what you like. It’s just me here, listening. Women bring forth in sadness. We fulfill the word, God’s judgment on Eve.”

“I’m not Eve. I don’t deserve this pain.” She clutches at Gutke’s stained skirt.

Gutke shrugs. “You know yourself pain is never a matter of deserving. We’ll get through this together. Watch my eyes.”