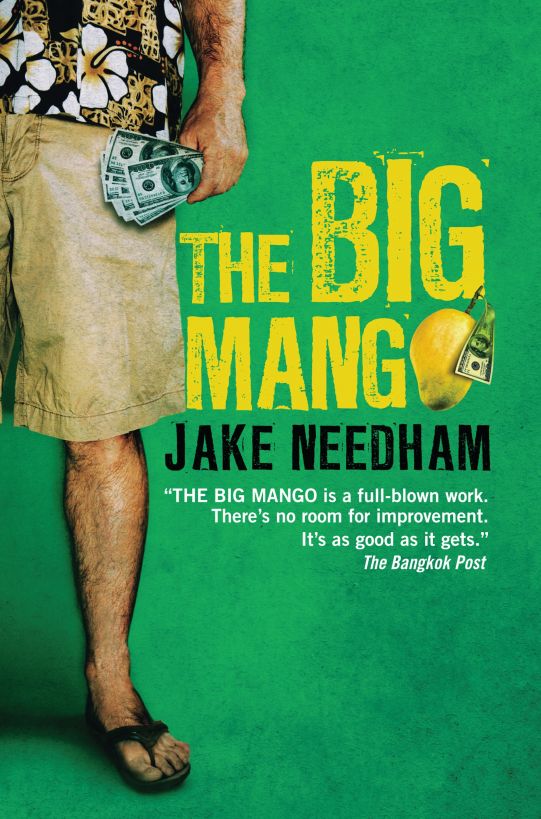

Big Mango (9786167611037)

Read Big Mango (9786167611037) Online

Authors: Jake Needham

Tags: #crime, #crime thrillers, #bangkok, #thailand fiction, #thailand thriller, #crime adventure, #thailand mystery, #bangkok noir, #crime fiction anthology

SAYS ABOUT JAKE NEEDHAM

“THE BIG MANGO is as good as it gets.”

--

The Bangkok Post

“No clichés. No BS. Thrillers written with a

wry sense of irony in the mean-streets, fast-car, tough-talk

tradition of Elmore Leonard. Needham has found acclaim as one of

the best-selling English-language writers in Asia.”

-- The Edge

(Singapore)

“Mr. Needham seems to know rather more than

one ought about these things.”

-- The Wall Street Journal

Asia

“Needham is Michael Connelly with steamed

rice.”

-- The Bangkok Post

“Needham is Asia’s most stylish and

atmospheric writer of crime fiction.”

-- The Straits Times

(Singapore)

“Jake Needham has a knack for bringing

intricate plots to life. His stories blur the line between fact and

fiction and have a ‘ripped from the headlines’ feel. Buckle up and

enjoy the ride.”

- CNNgo

“THE BIG MANGO is a witty, inventive, and

most of all thrilling thriller; a heady, bloody, luxurious, sordid

fictional romp.”

-- The Nation (Thailand)

A novel

by

Smashwords edition published by

Half Penny Ltd.

Hong Kong

THE BIG MANGO, copyright © 2011 by Jake

Raymond Needham

This e-book is licensed for your personal

enjoyment only. It may not be re-sold or given away to other

people. If you are reading this book and did not purchase it or it

was not purchased specifically for your use, please purchase a copy

for yourself. Thank you for respecting the work of the author and

the publisher.

Excerpt from LAUNDRY MAN, © 2011 by Jake

Raymond Needham

Smashwords ISBN:

978-616-7611-06-8

English-language print publication

history

First edition: Asia Books Co Ltd, Bangkok,

1999, ISBN 974-8237-36-2

Second edition: Chameleon Press, Hong Kong, 2002, ISBN

962-86319-4-2

Third edition: Marshall Cavendish International, Singapore, 2010,

ISBN 978-981-4276-60-3

All e-book editions published by Half Penny

Ltd, Hong Kong

Smashwords Edition October 2012

What the Press Says About Jake

Needham

Aey, James, and Charles.

But then, everything is

for them

.

I would

be glad to know which is worst: to be ravished a hundred times by

pirates, to have one buttock cut off, to run the gauntlet among the

Bulgarians, to be whipped and hanged at an auto-de-fen, to be

dissected, to be chained to an oar in a galley; and, in short, to

experience all the miseries through which every one of us hath

passed … or to remain here doing nothing?”

“This,” said Candide, “is a grand question.”

Voltaire

Candide, 1759

ON

April 21, 1975, sometime

late in the afternoon, Nguyen Van Thieu abruptly resigned as

president of the Republic of South Vietnam and abandoned to the

North Vietnamese what little was left of his weary and wasted

country.

Just before dawn the following morning, a

C-118 belonging to the South Vietnamese Air Force rolled almost

unnoticed down a darkened runway at Tan Son Nhut. The plane was

heavy, crammed with boxes and crates that had been trucked to the

airfield from the Presidential Palace during the night. Gaining

altitude and turning its back on the approaching dawn, the big

plane crawled slowly into the moist early morning darkness and

lumbered away.

Four nights later, on April 25, an aging

DC-6 provided by the American Ambassador flew Thieu and nine of his

confederates quietly out of Vietnam. Each of them was carrying a

document personally signed by President Gerald Ford authorizing

their entry into the United States.

By daybreak on April 26, the rumors were

racing through Saigon. Thieu and his cronies had fled, the whispers

went, but they had not gone empty-handed. The vaults of the Bank of

Vietnam were bare. Thieu had secretly spirited all the bank’s

reserves out of the country before he left.

It made a good story, but it wasn’t

true.

The C-118 that departed Tan Son Nhut in the

early morning darkness of April 22 carried only a few of Thieu’s

personal possessions and some government archives he hoped might

win him sympathetic treatment from future historians. The Bank of

Vietnam’s gold and foreign currency reserves were still there in

South Vietnam.

The rumors did have one thing right,

however. The reserves were no longer in the vaults of the Bank of

Vietnam. They were in the basement of a nondescript warehouse on

Phan Binh Street, a narrow, shell-cratered road just north of the

American Embassy. The currency and gold were there and not in the

bank’s vaults because the CIA had launched an operation to get them

out of the country before they fell into the hands of the North

Vietnamese.

Several weeks earlier, a United States

marine captain trusted by the CIA’s Saigon station chief had been

given the task of secretly preparing the reserves of the Bank of

Vietnam for shipment to safety, and he had done his job well. That

was no surprise to the station chief. He knew the officer to be a

reliable man, a bit of an oddball perhaps, but well educated,

intelligent, and resourceful. It was even said by some that he

wrote poetry, but the station chief had never read any of it

himself and he had never asked the captain if that were true.

That the man did have an intellectual bent,

however, was readily apparent from the code name he selected for

the undertaking. He called it Operation Voltaire. No one ever asked

him why.

Two American members of the CIA’s Saigon

station packed a total of almost 20,000 pounds of currency, mostly

American dollars, as well as a small amount of gold bullion into

wooden crates. Some embassy employees, locals who had no idea what

was in the crates, then trucked them to the warehouse on Phan Binh

Street. The captain organized a small detachment of marines to

guard the building and settled back to wait for orders to fly the

crates to safety outside of Vietnam.

Those orders never came.

As the noose around Saigon tightened, the

CIA pressed what was left of the South Vietnamese government to

approve the implementation of Operation Voltaire and allow them to

ship the Bank of Vietnam’s reserves to Switzerland, but the

frightened men abandoned by Thieu dithered. They clung to their

daydreams like drowning men to driftwood.

Maybe the North would accept a negotiated

settlement, they hoped against all reason. If it did, then letting

the Americans fly the Bank of Vietnam’s gold and foreign currency

out of the country would suddenly look like a very bad idea. After

the North Vietnamese took over, they would certainly tag anyone who

had been rash enough to endorse such a plan as a traitor, a label

that would undoubtedly prove fatal.

Then April 30, 1975, came, and it didn’t

matter anymore.

North Vietnamese artillery pounded the city

remorselessly, Saigon began to burn, and the population spiraled

into an ugly panic. The State Department ordered all remaining

Americans in Saigon evacuated, but it took a cordon of American

marines on the walls of the embassy compound, bayonets fixed to

their M-16s and thump guns popping canisters of tear gas into an

angry mob of Vietnamese, to make it possible.

By the time the last helicopter load of

Americans lifted off the roof of the gutted embassy building and

clattered through the dense smoke to the aircraft carriers waiting

in the South China Sea, the crates of currency and gold stored in

the warehouse on Phan Binh Street had become nothing but 20,000

pounds of excess baggage. Operation Voltaire was forgotten.

As the years passed, the few people who had

known about Operation Voltaire retired or died and the more

informed speculation about what happened to the Bank of Vietnam’s

reserves disappeared along with them. Within a little more than a

decade, the colorful story of a vast hoard of gold and currency

abandoned by the fleeing Americans in the flames of Saigon was

reduced to a footnote in the rich annals of Washington folklore.

Only half-believed at most, and even then only by a few, the tale

was filed away with Deep Throat and the grassy knoll and largely

forgotten.

Then, in 1995, reconciliation became the

flavor of the day. Vietnam and the United States resumed diplomatic

relations, reopened their embassies, and exchanged diplomatic

personnel.

The newly appointed second secretary at the

American Embassy in Hanoi, a position frequently reserved for a

senior intelligence officer, was a man who had begun his career,

not coincidentally, with a brief tour in Saigon in 1975. That

posting had been minor, he had been listed on the embassy personnel

roster as nothing more than a junior cultural attach, but the

second secretary was one of the few people still in public life who

knew for certain that the story of tons of money and gold left

behind in the ruins of Saigon was not folklore. And he had not

forgotten.

As far as the second secretary knew, no

trace of that 20,000 pounds of currency and gold had ever surfaced

anywhere, so the first time he found an excuse to travel from Hanoi

down to Saigon—now known as Ho Chi Minh City in what he thought a

particularly graceless brutalization of history—he naturally took a

stroll around to Phan Binh Street.

The warehouse was gone.

The second secretary glanced at the empty

space where it had once stood; he took in the mounds of broken

concrete and the rusting rebars that were all that remained; and he

walked on without stopping.

As nearly as the second secretary could

calculate with any certainty, the ten tons of gold and currency in

that warehouse in April 1975 would now be worth at least

$400,000,000. Since plainly the money was no longer where it had

been left, the second secretary thought he might ask around,

diplomatically of course, to find out what the North Vietnamese had

done with it after they rolled into Saigon.