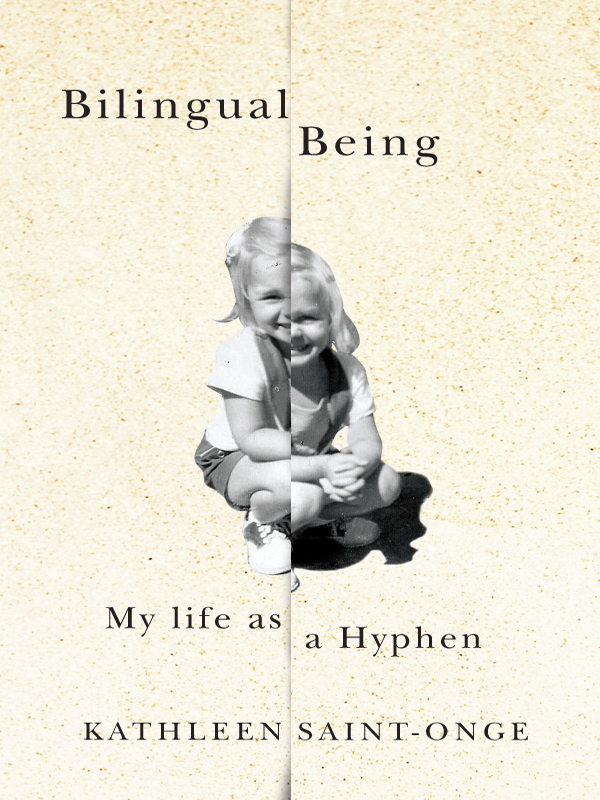

Bilingual Being

Authors: Kathleen Saint-Onge

BILINGUAL BEING

Bilingual Being

MY LIFE AS A HYPHEN

KATHLEEN SAINT-ONGE

McGill-Queen's University Press

Montreal & Kingston | London | Ithaca

© McGill-Queen's University Press 2013

ISBN

978-0-7735-4119-1

Legal deposit first quarter 2013

Bibliothèque nationale du Québec

Printed in Canada on acid-free paper that is 100% ancient forest free (100% post-consumer recycled), processed chlorine free

McGill-Queen's University Press acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program. We also acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for our publishing activities.

The epigraphs appearing on page 1 are from

Aesop's Fables

(trans. Vernon Jones: Kahley Publishing, 2007) and Jacques Derrida's

Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression

(trans. Eric Prenowitz: University of Chicago Press, 1996).

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Saint-Onge, Kathleen, 1957â

Bilingual being : my life as a hyphen / Kathleen Saint-Onge.

ISBN 978-0-7735-4119-1

1. Saint-Onge, Kathleen, 1957â. 2. Saint-Onge, Kathleen, 1957 â Childhood and youth. 3. Adult child sexual abuse victims â Québec (Province) â Québec â Biography. 4. Bilingualism â Québec (Province) â Québec. 5. Catholic Church âQuébec (Province) â Québec. 6. Québec (Québec) â Social conditions â 20th century.

I. Title.

HV

6570.4.

C

3S259 2013Â Â Â Â 362.76'4092Â Â Â Â

C

2012-908045-4

Set in 11.5/14 Adobe Garamond Pro with Scala Sans

Book design

&

typesetting by Garet Markvoort, zijn digital

Pis c'est pour toé surtout, c'te liv'-là ,

ma belle cousine Sonya.

Tu rêva' bin d'enseigner l'angla' itout un jour,

mais là , tu respire l'air fra' du ciel pour tou'es jours.

En haut, ousse que t'es, tu-vois-tu nos vra' pères là bas â

ceux qu'y ont mangé tant d'not'merde pour c't'affaire-là ?

T'sais, t'as perdu ta voix binque trop jeune,

mais moé, j't'entends encore quand même.

C'fa'q'ej dédie c'te travail-là bin fort à ton honneur,

pis el maudit silence, on l'perce ensemb' astheure.

[And it's for you most of all, this book,

my beautiful cousin, Sonya.

You, too, dreamt of teaching English some day,

but now, you breathe the fresh air of heaven every day.

Up where you are, do you see our actual fathers there â

those who ate so much of our shit because of this mess?

You know, you lost your voice far too young,

but as for me, I still hear you anyhow.

So I dedicate the present work sincerely in your honour,

and the damned silence, we pierce it now, together.]

CONTENTS

1 My Mother Tongue/My Mother's Tongue

3 A New Linguistic Landscape

8 Religion: The Language of the Bedroom

9 My Brother: My Flip Side

POEMS

Letter

Dear Elder,

Did I make you nervous?

Or did you just happen to dislike me?

At parties, you didn't look me in the eye.

I never got a hug or smile, or conversation.

You were austere and unapproachable â

but why only with me?

Was my mother right?

Is this what I brought upon myself,

simply by becoming “so damned English” â

«mauditement froide pis indépendante»?

*

Rejecting «ma patrie» for elsewhere,

and for this other tongue?

Or was my mother wrong?

Did you remember all along

what I'd forgotten until now?

Were you afraid my memory would trigger,

so you helped me move away from home,

by showing me I was already absent?

Is that it, my dear Elder?

Because if it is, then I think history

will reveal that when our culture foundered,

and our folk abandoned distant shores,

it was too late for us to run, or hide.

The enemy was among us, deep inside.

Signed,

«Une p'tite fille d'l'famille»

__________

*

Damned cold and independent (the latter being a very harsh criticism in French-Canadian culture, certainly not intended as a compliment).

Clockwork

«C'est l'temps qui passe

entre deux mains.»

*

One, two:

decade through.

Hands right on time.

Movements as regular

as clockwork.

One. 1963.

A crowd in here.

The dark red folding chairs

in the basement in the suburbs.

Family party. Too much champagne.

Miscellaneous uncles and male friends.

Two hands appear underneath my rump

under my dress, touch my frilly underwear.

That's precisely when the mechanism triggers,

the numbing switch. Controls skin, mind, soul.

Sensing fingers, as if anaesthetized but awake.

As if pressure pushes a perfectly frozen self,

looking at the girl sitting on the lap.

It is not necessary for someone

to intervene. Someone has.

I feel nothing

but time.

Two. 1973.

Alone down here.

The little orange couch

in the basement in the suburbs.

Weekend evening. Too much beer.

My date, a year older, already driving.

Two hands appear underneath my rump

under my jeans, touch my cotton underwear.

That's precisely when the mechanism triggers,

the numbing switch. Controls skin, mind, soul.

Sensing fingers, as if anaesthetized but awake.

As if pressure pushes a perfectly frozen self,

looking at the girl sitting on the lap.

It is not necessary for someone

to intervene. Someone has.

I feel nothing

but time.

__________

*

“This is (the) time spent (passing) between two hands.”

PROLOGUE

Apologia: A formal defence of a position or belief

There's a classic French children's song, «Chère Ãlise,» about a girl who has a little hole in her bucket. It's famous, if that can be said about old songs and rhymes. I could hear it daily, weekly, in the songs of my mother, my grandmother, my great-grandmother â around my home, my street, my world, Quebec City. From the year I was born, 1957, a story from the knee, and after that, year by year. I hear it resonate in my head even as I write this.

In my mind, the voice is usually my mother's, and I try to join in, to echo the string of tricky phrases. There's a wave of tones, rising and falling, and some forgetting and laughing, and the comforting sensation that this Ãlise is at least a bit funny if not terribly smart â and that her song is a bit soothing though tiresome too. For me, Ãlise has many dimensions in French, complexity and depth. There's feeling wrapped up inside her â the smells and sounds of both ordinary and special days, remembrances of time past and moments never quite erased, however the years have unravelled their difficult scenarios.

In French, she's opaque, tangible, and sensual. And so her song has a place in the treasures of my childhood, a particular place of its own, like my soft cat with the plastic face and chewed-off ear. Or my favourite pink «jaquette en flannalette» [flannel nightie], as the language of home said then. A «jaquette de flanelle,» as the “reformed” language of home says now.

In English, the song's called “Dear Liza,” but I don't know it half as well. I have a sense that not so many people sing it in English, but I'm

told many do â anglo children. In English, there's no accompanying music in my head, no memories, no echoes, no presence of this material registering psychically in any way. But I can convert the words easily enough. In English, Liza is, becomes, a translation rather than a person. Transparent, constructed. A projection of Ãlise. Purely linguistic.

It's a classic children's round, its humour based on an interminably repetitive narrative. There's a hole in the bucket and Liza doesn't know how to fix it. What should she do? She needs straw to plug the hole. But the hay isn't cut. She needs a sickle. But the sickle isn't sharp enough. She needs a sharpening stone. But the stone isn't wet. She needs water. But the water hasn't been brought up from the well yet. She needs to fetch water. But there's a hole in the bucket.

Ah, poor Liza. She's a bit of a dunce, this girl, neither terribly autonomous nor independent. And quite illogical, too, no? Circular, even. As though everything she needs to do hinges on something before it, and that thing itself leans on something else that must be done before that ⦠and when she backs up completely toward the past, step by step, she's right back where she started. We regard her with a kind of pity that we somehow don't feel.

Ãlise

and

Liza. Ãlise

or

Liza. We perceive our protagonist slightly differently in each of her languages, don't we? Her identity seems changed, and her personality is subject to reinterpretation, this way or that. Academics might say she has a presentation of self that varies with her languages as her bilingual identities play out like alters, fluctuating and flickering, influenced by the passions of affect, culture, and the primary allegiances of the soul. Our young multilingual, multicultural subject is quintessentially postmodern, multiple, fragmented, hybrid, liminal, fluid. A pin-up girl for the times. Chic split.

Is she a bilingual mess or a psychological virtuoso? It's hardly a question of interest to her. For all that she cares about other than that broken bucket is that she exists â she survives. The question of far greater value is how it feels for Ãlise-Liza to live like this, with a foot in each language. Is she comfortable? Happy? Does she enjoy playing in the wide space between her worlds â or does she feel lost between them? Does she belong everywhere, to everyone â or nowhere, to no one? And what's the impact of her shifting loyalities on those who love her and interact with her in one language or the other?

Now let's imagine that one day, as Ãlise-Liza is walking with her problematic bucket, she runs into a charming young woman her age who's also carrying a bucket, and they begin a cheerful conversation. The new friend, Jill, speaks only English. But Ãlise-Liza puts her bilingualism to good use in the months that follow, as they meet at the well each day. That's how Ãlise-Liza learns that Jill has a brother named Jack who's responsible for carrying water to the well, too. Some days Jack comes along with Jill, while on other days he runs out of the house and does it on his own. Ãlise-Liza is fascinated by this idea that a boy can do the well chore, while a girl can choose to avoid it.

When she returns home, the usual drips following behind her on the ground, she's still dreaming of her new friend, Jill, and this other world. Of course, she says nothing of what she's thinking, for it's her private world, too precious to share even with her own mother. So she feels herself becoming a bit distant from her family, with her own thoughts. And she looks forward to each day's trip to the well to learn more. Her mother watches her skip away into the distance and yells after her, «Erviens bin vite!» [Come back fast!] But Ãlise-Liza does not come back quickly. She lingers at the well as long as she can, delighted to think of new possibilities for her life, ignoring the dripping bucket.