Bind, Torture, Kill: The Inside Story of BTK, the Serial Killer Next Door (7 page)

Read Bind, Torture, Kill: The Inside Story of BTK, the Serial Killer Next Door Online

Authors: Roy Wenzl,Tim Potter,L. Kelly,Hurst Laviana

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #Serial murderers, #Biography, #Social Science, #Murder, #Biography & Autobiography, #Serial Murders, #Serial Murder Investigation, #True Crime, #Criminology, #Criminals & Outlaws, #Case studies, #Serial Killers, #Serial Murders - Kansas - Wichita, #Serial Murder Investigation - Kansas - Wichita, #Kansas, #Wichita, #Rader; Dennis, #Serial Murderers - Kansas - Wichita

I don’t think you want to, Rader shouted back. I’ll blow your head off!

With the shades drawn, it was dark in the bedroom at midday. He made the woman lie facedown on the bed, her head at the foot of it. He tied her feet to the metal head rail, and ran a long cord to her throat.

She threw up on the floor.

Oh, well

, he thought.

She said she was sick

. And he had said this would not be pleasant.

Not for her, anyway.

He walked into the kitchen and fetched her a glass of water, to comfort her, or so he said later. He considered himself a nice guy. When Julie Otero had complained that her hands were going numb from her bindings, he had adjusted them. When Joe had said his chest hurt from lying on the floor with broken ribs, he had fetched Joe a coat to rest on. Now, in the darkened bedroom of the house on Hydraulic, he gave the sick woman a sip of water.

Then he took a plastic bag out of his hit kit and pulled it over her head. He took the cord that was tied to the bed and wrapped the far end of it around her throat four or five times, along with her pink nightie.

And he pulled. He had rigged the cord so that it tightened as she struggled. The kids screamed louder and hammered their hands on the wooden door as their mother died.

He stood up, disappointed.

He wanted to do more�suffocate the boys, hang the girl. But the phone call worried him.

Before he walked out, he stole two pairs of the woman’s underpants.

Bud, the eight-year-old, picked up something hard and shattered the bottom pane of the bathroom window. They were all still screaming, and Steven now worried that Bud would get in trouble for breaking the window. But after Bud crawled out, Steven followed, dropping to the ground. They ran to the front door, then into their mother’s bedroom.

They found the man gone, their mother tied up, a bag over her head. She was not moving.

At 1:00

PM

a police dispatcher radioed a cryptic message to Officer Raymond Fletcher: “Call me back on a telephone.” Dispatchers asked for a telephone call when they wanted to have a private conversation not broadcast on police scanners. When Fletcher called, the dispatcher gave him an address and said there was a report of a homicide.

On South Hydraulic, James Burnett waved Fletcher down and said that two neighbor children had come screaming to his house. His wife, Sharon, had run to the boys’ home. In the living room, she saw a little girl sitting on the floor, sobbing. In the bedroom, Sharon Burnett found their dead mother.

Bud Relford broke the bathroom window and escaped to alert the neighbors.

James Burnett led Fletcher to Shirley Vian’s house. An ambulance was on the way. Fletcher, a former emergency medical technician, searched for a pulse as soon as he saw her, just as he had when he was one of the first two officers to walk into Kathryn Bright’s house. He felt a twitch under his fingertips, not a pulse but something faint. Fletcher yanked off the cord and nightie, but took care to leave the knots intact. He began CPR, pushing on the woman’s chest. Firefighters were coming in. He told them to preserve the knots�they were evidence.

It was so dark with the blinds drawn that they could barely see. They carried the woman to the living room and restarted CPR.

It was too late.

Fletcher radioed dispatch. Send detectives, he said. It’s a homicide.

In the living room, Fletcher saw the girl sitting on a couch, still crying.

He carefully laid the knots aside and studied the rooms and the body. It did not occur to him that this murder could have been committed by the same guy who had killed Kathryn Bright. Aside from a trickle coming from Shirley’s ear, there was no blood. But something about this scene rang bells with him: the knots and multiple bindings, the bag over the woman’s head. He had seen things like this written about in the Otero reports. He remembered that Josie Otero had been sexually defiled. Fletcher searched the house, looking for semen stains. He did not find any, but he called dispatch.

Stephanie Relford was found crying in the living room when the police arrived.

“It looks like the same thing as the Otero case.”

A lot of cops who showed up at Shirley Vian’s house thought the same thing. Bob Cocking, the sergeant assigned to secure the crime scene, said it out loud to detectives when they arrived. They whirled around and told him he did not know what he was talking about. Cocking, feeling insulted, walked away.

But it wasn’t just detectives arguing with officers. They argued with each other. Supervisors told them to stop guessing and work the evidence. If BTK had killed Shirley Vian, it meant he was a serial killer, and the brass didn’t want to leap to that conclusion or set off a panic.

Some of the cops were already leaking information that would get into the next day’s newspaper. Their supervisors then stepped outside and said the evidence of a link was unclear.

The

Eagle

’s new police reporter, Ken Stephens, didn’t buy that and wrote a story that noted similarities in the Otero and Vian crimes.

The plastic bag and rope Rader used to kill Shirley Vian on her bed.

Bill Cornwell, head of the homicide detectives, had visited the Vian scene “just to make sure it wasn’t the Otero killer again.” He privately noted a number of differences between the cases: there was no semen and no cut phone line at Shirley’s house. The Otero children died; Shirley’s children survived. But his gut told him it might be the same guy.

Cornwell and LaMunyon also briefly considered whether this case might be linked not only to the Oteros but to the unsolved murder of Kathryn Bright. Most detectives still thought someone else killed Bright. So did Fletcher, a first responder at the Bright and Vian crime scenes.

Shirley’s children tried to help the cops.

Steven, the six-year-old, broke down and cried and told them everything he had seen. He had gone for soup, talked to man with a briefcase about a photograph, then let the man in. He blamed himself for that. He had let in the man who killed his mother. He said the man was dressed real nice. He described a man who was in his thirties or forties and had dark hair and a paunch. But as the boy talked, a uniformed officer walked up.

Shirley Vian’s body is taken to be autopsied.

The boy pointed.

The bad guy looked like that man, the boy said.

The detectives looked at the officer: tall, in his twenties, with a trim, athletic body. No paunch. The detectives glanced at each other and closed their notebooks. The boy’s description was useless.

By this time, investigators, including Cornwell, had rejected a theory they had clung to for a long time: that the Oteros died in a drug-related revenge killing.

Bernie Drowatzky, one of Cornwell’s better detectives, had been proposing another idea. Some of his bosses didn’t think much of it, but Drowatzky was saying that maybe they were dealing with a sex pervert who chose his victims at random. And if the guy who killed the Oteros had now killed Shirley Vian, that meant he was a serial killer.

No, no, other cops said. The FBI said serial killers were incredibly rare.

LaMunyon was not a detective, but instinct told him it was the same guy. It seemed obvious. But saying this publicly might cause a panic. If the evidence was there, he would stand before the notepads and TV cameras and say it. It would be embarrassing to admit he could not protect people, but if that was the truth, then he needed to warn people.

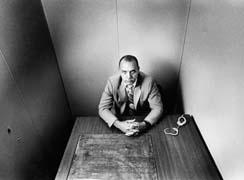

Bernie Drowatzky, one of the primary detectives during the early years of the BTK investigation.

In the days that followed Shirley’s murder, LaMunyon and the detectives reviewed every similarity and difference. The Otero killer had boldly walked in on them. This killer had walked in on Shirley and her children. The Otero killer had tied hands behind backs; so had this guy. The Otero killer had tied Joe Otero’s ankles to the foot of his bed; this killer had tied Shirley’s feet to a headrail. At both scenes, a killer had pulled a plastic bag over someone’s head.

The cops had not turned up a single useful fingerprint at either house.

Some detectives argued there was not enough evidence to link the murders. What about the differences?

The differences looked small, LaMunyon said.

Detectives pointed out something else: the experts said serial killers couldn’t stop once they started. The FBI had only recently begun to study serial killers in depth, but it was saying that no serial killer had taken three years off. It was probably not the same guy.

In the end, based on the advice of some of his detectives and his own desire to be more sure before risking public panic, LaMunyon decided to not make an announcement. He thought publicity might inspire BTK to kill again. He made the decision with one grim thought: the strangler would probably make it necessary to change his mind.

Steven Relford, Shirley Vian’s youngest son, would grow up bitter, drinking, drugging, and paying artists to cover his body with skull tattoos. He would remember the screaming.