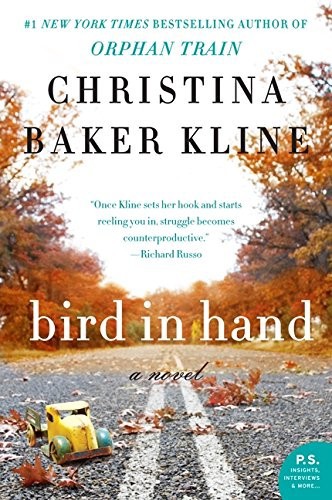

Bird in Hand

Authors: Christina Baker Kline

It is a queer and fantastic world. Why can’t people have what they want? The things were all there to content everybody; yet everybody has the wrong thing.

The Good Soldier

Contents

For Alison, these

things will always be connected: the moment that cleaved her life into two sections and the dawning realization that even before the accident her life was not what it seemed. In the instant it took the accident to happen, and in the slow-motion moments afterward, she still believed that there was order in the universe—that she’d be able to put things right. But with one random error, built on dozens of tiny mistakes of judgment, she stepped into a different story that seemed, for a long time, to have nothing to do with her. She watched, as if behind one-way glass, as the only life she recognized slipped from her grasp.

This is what happened: she killed a child. It was not her own child. He—he was not her own child, her own boy, her own three-year-old son. She was on her way home from a party where she’d had a few drinks. She pulled out into an intersection, the other car went through a stop sign, and she didn’t move out of the way. It was as simple as that, and as complicated.

Something happens to you in the moments after a car crash. Your brain needs time to catch up; you don’t want to believe what your senses are telling you. Your heart is beating so loudly that it seems to be its own living being, separate from you. Everything feels too close.

As she saw the car coming toward her she sat rigid against the seat. Shutting her eyes, she heard the splintering glass and felt the wrenching slam of metal into metal. Then there was silence. She smelled gasoline and opened her eyes. The other car was crumpled and steaming and quiet, and the windshield was shattered; Alison couldn’t see inside. The driver’s door opened, and a man stumbled out. “My boy—my boy, he’s hurt,” he shouted in a panicky voice.

“I have a phone. I’ll call 911,” Alison said.

“Oh, God hurry,” he said.

She punched the numbers with unsteady fingers. She was shaking all over; even her teeth were chattering.

“There’s been an accident,” she told the operator. “Send help. A boy is hurt.”

The operator asked where Alison was, and she didn’t know what to say. She’d taken a wrong turn awhile back, gone north instead of west, and found herself on an unfamiliar road. She knew she was lost right away; it wasn’t like she didn’t know, but there had been nowhere to turn, so she’d kept going. The road led to other, smaller roads, badly lit and hard to see in the foggy darkness, and then she came upon a four-way stop. Alison had pulled out into the intersection before she’d realized that the other car was driving straight through without stopping—the car was to her right and had the right of way, but it hadn’t been there a moment ago when she had moved forward. It had seemed, quite literally, to have come out of nowhere.

Alison knew better than to explain all this to the operator, but in truth she had no idea where she was. Craning her neck to look out the windshield, she saw a street sign—Saw Hill Road—and reported this.

“Hold on,” the operator said. “Okay, you’re in Sherman. I’ll send an ambulance right away.”

“Please tell them to hurry,” Alison said.

She called her husband from the hospital and told him about the accident, about the car being totaled and her injured wrist, but she didn’t tell him that all around her doctors and nurses were barking orders and the swinging doors were banging open and shut, and a small boy was at the center of it, a small boy with a broken skull and a blood-spattered T-shirt. But Charlie knew soon enough. She had to call him back to tell him not to come to the hospital; she was now at the police station, and there was silence for a moment and then he said, “Oh—God,” and whatever numbness she’d had was stripped away. She flinched—told him, “Don’t come”—and he said, “What did you do?”

It wasn’t the response she’d expected—not that she had thought ahead enough to expect anything in particular; she didn’t know what to expect; she didn’t have a response in mind. But her sudden realization that Charlie was not with her, not reflexively on her side, was so profoundly shocking that she braced for what was next.

“Do we need a lawyer?” he said when it was clear she wasn’t going to answer, and she said, “I don’t know—maybe. Probably.”

“Don’t say anything,” he said then. She could tell he was flipping through scenarios in his mind, trying to lay things out in a methodical way. “Just wait until I get there.”

“But I already said everything. A boy is—a little boy is—they don’t know yet—hurt.” She said this, although they’d already told her there was swelling on the brain. The police weren’t wearing uniforms, and they didn’t handcuff her or read Alison her rights or any of the other things she might have expected. The boy’s parents were weeping; the mother was wailing

I let him sit on my lap; he was cold in the back and afraid of the dark

, and the father was slumped with his hands over his face. The walls of the lobby vibrated with their sadness.

“Jesus Christ.” Charlie breathed. And she thought of other times he’d been exasperated with her—on their honeymoon, when, after two days of learning to ski, she suddenly froze up and couldn’t do it; she was terrified of the speed, the recklessness, of feeling out of control; she was sure she would break a limb. So she spent the rest of the time in the lodge, a calculatedly cozy place with a gas flame in the fireplace and glossy ski magazines on the oak veneer coffee tables, while Charlie got his money’s worth from the honeymoon. She tried to think of an experience comparable to what was happening now, some time when she had done X and he had reacted Y, but she couldn’t come up with a thing. Eight years. Two children. A life she didn’t plan for but had grown to love. Friends and a hometown and a house, not too big but not tiny, either, with creaky stairs and water-damaged ceilings but lots of potential.

Potential was something she once had a lot of, too. Every paper she wrote in college could have been better; every B+ could have been an A. She could have pushed ahead in her career instead of stopping when it became easier to do so. She hadn’t known she wanted to stop, but Charlie said, “C’mon, Alison, the kids want you at home. It’s a home when you’re home.” But after she quit he complained about bearing the heavy load of responsibility for them. There was no safety net, he said; he said it made him anxious. He wanted her at home, but he missed the money and the security, and she knew he missed seeing her out in the world, though he didn’t say it. He saw her at home in faded jeans and an old cotton sweater, he saw her at seven o’clock when the kids were clamoring for him and strung out and cranky and he had just endured his hour-long commute from the city.

And yet—and yet she thought she was lucky, thought they were lucky, loved and appreciated their life.

But tonight she was living a nightmare. Her friends—some of them, at least—would probably try to comfort her, provide some kind of solace, but it would be hard for them, because deep down they would think that she was to blame. And it wasn’t that they couldn’t imagine being in her position, because every mother has imagined what it would feel like to be responsible for taking the life of someone else’s child.

But worse, every mother has thought about what it would be like to have her child’s life taken from her.

Alison could hear Charlie asking for her, out at the front desk. Polite and deferential and panicked and impatient—all of that. She could read his voice the way some people read birdcalls. She almost didn’t want him to find her. As she looked around at the dingy lights, the dirt-sodden carpet, heard the clatter from the holding cells down the hall, she wondered what it would be like to stay here—not here, perhaps, but in prison somewhere, cut off from other people, penitent as a nun. Or in a convent, a place with stone walls, small slices of sky visible through narrow slits, neatly made narrow beds. A place where she could pay for this quietly, away from anyone who had ever known her.

You might expect that she’d have thought of her children, and she did—peripherally, like a blinkered horse looking sideways; when she tried to think of them straight on, her mind went blank. Her own boy’s brown curls on the pillow, her six-year-old daughter’s twisted nightgown, her covers on the floor … Alison saw them sleeping, imagined them dead—just for an instant. Imagined explaining—and stopped. The only thing she seemed able to do was concentrate on the minute details of each moment: the cold floor, hard seat, dispassionate officers tapping on keyboards and shuffling papers. The tick of the wall clock: 11:53.

At a four-way stop every vehicle must come to a complete halt before proceeding one at a time across the intersection, regardless of whether there is any other traffic in sight or not.

If two or more vehicles draw up to one of these junctions and stop, waiting to proceed across it, then they should proceed in the same order in which they arrived. If two vehicles arrive at one of these junctions at precisely the same time, so that it is impossible to tell which arrived first, then in theory the vehicle on the right has priority. However, many drivers are unaware of this rule and there are complications due to all the possible permutations of turns.