Black Genesis (29 page)

BLACK GENESIS: YEAR ZERO

We in the modern world consider the Year Zero of our calendar to be the presumed birth of Jesus, which, today, is thought to have been 2,010 years ago.

*54

This, however, is purely an arbitrary date. Indeed many other peopleâsuch as the Muslims, the Jews, the Chinese, and the Japaneseâhad (and some still have) other Year Zeroes for their own calendars. Usually, years are numbered from the date of a historical person, either an ancient person, as in the case of the Muslim, Jewish, and Christian calendars, or a sequence of emperors, as in ancient China or modern Japan, where legal documents are dated “year Heisei 22.”

When was the Year Zero of the ancient Egyptians? How can we calculate its date? This is where we can note an interesting issue regarding study of the drift of the civil calendar relative to the heliacal rising of Sirius.

Sirius was known as the Sparkling One, the Scorching One, or, less flatteringly, the Dog Star or Canicula.

â 55

These epithets derived from the fact that the heliacal rising of this star occurred in midsummer, when the sun was at its hottestâthe so-called dog days of the Roman year. The Greeks called this star Sothis, a name that perhaps derived from the ancient Egyptian Satis, the goddess of the Nile's flood at Elephantine whom the Egyptians identified with

Sirius.

55

Modern astronomers know it as Alpha Canis Major or by its common name, Sirius. It is the star that shines the brightest in the skyâits brightness in absolute terms is twenty-three times the brightness of our sun. It is also twice as massive as our sun and much hotter, and its 9,400-degrees-Kelvin temperature makes it appear to be brilliant white. The American astronomer Robert Burnham Jr. tells us that it is “the brightest of the fixed stars . . . and a splendid object throughout the winter months for observers in the northern

hemisphere.”

56

The star Sirius, however, does not stand alone. It is, in fact, part of a bright constellation we call Canis Major, the Big Dog, which trails behind Orion the Hunter. As the brightest of all the visible stars, Sirius is almost ten times more brilliant than any other star and can be seen in broad daylight with the aid of a small telescope. Its color is a brilliant bluish white. Quite simply, it is the crown jewel of the starry world.

When the very first pyramid in Egypt was built around 2650 BCE, Sirius rose at azimuth 116 degrees near modern Cairo. In 6000 BCE, when the prehistoric astronomers of the Sahara also observed it, Sirius rose at azimuth 130 degrees at Nabta Playa. As we can see in appendix 1, in the centuries around 11,500 BCE, Sirius rose almost due south at azimuth 180 degrees as seen from the Cairo area. It is a well-established fact that the Egyptians observed the rising of Sirius, especially its heliacal rising, since at least 3200 BCE. Because of the effect of precession, the time and place on the horizon of the heliacal rising of Sirius will slowly change. Today it takes place in early August. In 2781 BCE the rising occurred on June 21, the day of the summer solstice, when the Nile also began to rise with the coming flood. Of course, this propitious conjunctionâthe summer solstice, the heliacal rising of Sirius, and the start of the flood seasonâwould have been so for the prehistoric people of the Sahara, except that it was the playa flood season that started with the monsoon season.

The Nile and the New Year

The summer solstice may have originally marked the first day of the civil calendar. This idea was first proposed in 1894 by the astronomer Sir Norman Lockyer. The German chronologist E. Meyer also proposed it in 1908. Recently the Spanish astronomer Juan Belmonte revived this idea and further proposed that the summer solstice was the basis of the original calendar. According to the archaeoastronomer Edwin C. Krupp:

In ancient Egypt this annual reappearance of Sirius fell close to the summer solstice and coincided with the time of Nile's inundation. Isis, as Sirius, was the “mistress of the year's beginning,” for the Egyptian New Year was set by this event. New Year's ceremony texts at Dendera say Isis coaxed out the Nile and caused it to swell. The metaphor is astronomical, hydraulic, and sexual, and it parallels the function of Isis in the myth. Sirius revives the Nile just as Isis revives Osiris. Her time of hiding from Set is when Sirius is gone from the night sky. She gives birth to her son Horus, as Sirius gives birth to the New Year, and in texts Horus and the New Year are equated. She is the vehicle for renewal of life and order. Shining for a moment, one morning in summer, she stimulates the Nile and starts the

year.

57

The British astronomer R. W. Sloley reminds us, and with good reason, that “ultimately, our clocks are really timed by the stars. The master-clock is our earth, turning on its axis relative to the fixed

stars.”

58

Further, the American astronomer and director of the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles, Ed Krupp, points out that “celestial aligned architecture and celestially timed ceremonies tell us our ancestors watched the sky accurately and

systematically.”

59

What we may most want to know is whether Egyptians also used the stars for long-term computations of time, such as the Sothic cycle of 1,460 years. Perhaps this is why the ancient Egyptians deliberately opted not to have the leap yearâso that their slipping calendar could also work for long-term Sothic dates.

Providence would have it that a Roman citizen named Censorinus visited Egypt in the third century CE and witnessed the festivities in Alexandria that marked the start of a new Sothic cycle. This is what he reported: “The beginnings of these [Sothic] years are always reckoned from the first day of that month which is called by the Egyptians Thoth, which happened this year [239 CE] upon the 7th of the kalends of July [June 25]. For a hundred years ago from the present year [139 CE] the same fell upon the 12th of the kalends of August [July 21], on which day Canicula [Sirius] regularly rises in

Egypt.”

60

To put it more simply, the Egyptian New Year's Day (1 Thoth of the Egyptian calendar) recoincided with the heliacal rising of Sirius in the year 139 CE.

*56

Egypt was at that time a dominion of Rome and was ruled by Emperor Antonius Pius. This calendrical-astronomical event was clearly regarded as having great importance and was commemorated on a coin at Alexandria bearing the Greek word

AION,

implying the end or start of an era. At any rate, this information provided modern chronologists with an anchor date from which they could easily work out the start of previous Sothic cycles by simply subtracting increments of 1,460 years from 139 CE. Thus we know that Sothic cycles began on 1321 BCE, 2781 BCE, 4241 BCE, and so forth. Yet do the Sothic cycles hark back ad infinitum, or is there a Year Zero, as in other calendrical systems?

Even though the ancient Egyptians were obsessed with the idea of eternity, they also believed in a beginning of a secular time they called Zep Tepi, literally, the First Time. The British Egyptologist Rundle T. Clark comes tantalizingly close to the very heart of ancient Egyptian cosmogony when he writes that all rituals and feasts, most of which were linked to the cycle of the year, were “a repetition of an event that took place at the beginning of the

world.”

61

According to Clark,

This epochâ

zep tepiâ

“the First Time”âstretched from the first stirring of the High God in the Primeval Waters. . . . All proper myths relate events or manifestations of this epoch. Anything whose existence or authority had to be justified or explained must be referred to the “First Time.” This was true for natural phenomena, rituals, royal insignia, the plans of temples, magical or medical formulae, the hieroglyphic system of writing, the calendarâthe whole paraphernalia of the civilization . . . all that was good or efficacious was established on the principles laid down in the “First Time”âwhich was, therefore, a golden age of absolute

perfection . . .

62

The start of Sothic cycles, as we have seen, can be computed simply by moving backward or forward in increments of 1,460 years using Censorinus's anchor point of 139 CE. At the resulting years of Sothic cycles, the heliacal rising of Sirius coincided with New Year's Day (1 Thoth) of the calendar of ancient Egypt, but can we track these cycles back to Zep Tepi, the First Time . . . to the Year Zero of this calendar?

THE GREAT PYRAMID AND ZEP TEPI

In 1987, Robert Bauval sent a paper to the academic journal

Discussions in Egyptology

presenting a new and controversial theory on the Giza pyramids. The theory had been developed when, in 1983, Bauval was working in Saudi Arabia in the construction industry. One night while there, in the open desert, he made an unusual discovery involving the stars of Orion's belt and the Giza pyramids. While looking at the three stars of Orion's belt, it struck him that their pattern and also their position relative to the Milky Way uncannily resembled the pattern formed by the three pyramids of Giza and their position relative to the Nile. This curious similarity did not seem a coincidence, for not only did the ancient Pyramid Texts identify Orion with the god Osiris, who in turn was identified with the departed kings, but the ancient Egyptians also specified Orion as being in the celestial

Duat.

63

The correlation between the three stars of Orion's belt and the three pyramids of Giza was striking, if only for one reason: Orion's belt is made up of two bright stars and a less bright third star. This last is slightly offset to the left of the extended alignment created by the two other stars, much the same way that the third, smaller pyramid is slightly offset from the other two.

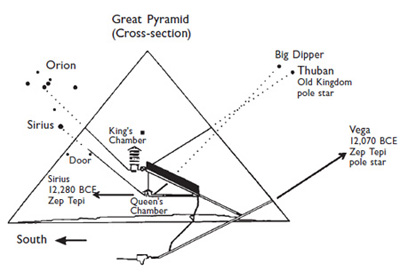

A fact that adds to this correlation was discovered in 1964 by two academics from UCLA, the Egyptologist Alexander Badawi and the astronomer Virginia Trimble, who proved that a narrow shaft emanating southward and upward from the King's Chamber in the Great Pyramid had once pointed to Orion's belt in about 2500 BCE, the date traditionally ascribed to the building of this monument. Later, in 1990, Bauval published another article in

Discussions in Egyptology

showing that from the Queen's Chamber is another shaft that points to the star Sirius at that same date. In 1994, Bauval published

The Orion Mystery,

which presented his theory to the general public.

*57

Figure 6.1. The pyramids of Giza and the stars of Orion's belt as they appeared in 2500 BCE and 11,500 BCE

The book, which has been the subject of numerous television documentaries, caused quite a stir at the time of its publiction and is still the subject of much controversy. More recently, in his book

The Egypt Code,

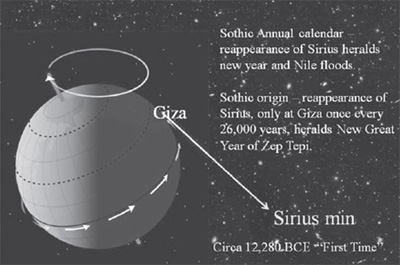

Bauval puts forward the final conclusion that the Giza pyramids may have been modeled on an image of Orion's belt not at the time of their presumed construction circa 2500 BCE, but at a much earlier time, circa 11,450 BCE. In other words, in deciphering the astronomy embedded in the design of the Giza pyramids, we can note the locking of two dates: 2500 BCE, which marks the time of construction, and 11,500 BCE, which marks the significant time that might allude to the First TimeâZep Tepi. This is our reasoning: If today you observe from the location of Giza the star Sirius cross the meridian it will be at 43 degrees altitude. If you could see the same event in 2500 BCE when the Great Pyramid was built, Sirius would have culminated at 39.5 degrees altitude, which is where the south shaft of the Queen's Chamber was aimed. Going even further in time the altitude of Sirius would drop and drop until, at about 11,500 BCE, Sirius would be just 1 degree altitude. Beyond this date Sirius would not have been seen at all because it would not break above the horizon.

In appendix 1 we look in detail at the motion of Sirius and find that Giza was actually the place on Earth where Sirius went down to rest briefly exactly on the horizon at the lowest point of its twenty-sixthousand-year cycle, and that occurred basically in this same epoch, circa 12,280 BCE. Further, we find that the light of the Mother of All Pole Stars, Vega, shone down the subterranean passages at Giza and Dashur in the same epoch, 12,070 BCE. In appendix 1 we also review how the Orion's belt-to-pyramids layout dates are also in this same general epoch. It is now well accepted that in the Great Pyramid the southern shaft of the Queen's Chamber marks the date of 2500 BCE, around the construction date of the monumentâbut what other shaft elsewhere in the Great Pyramid marks Zep Tepi?

The internal design of the Great Pyramid has been the source of numerous theories, none of which have provided a satisfactory solution to the many questions it poses or solves the great mystery that has baffled generations of researchers. In spite of this, Egyptologists are nonetheless adamant that the Great Pyramid served a funerary purpose, and they point for evidence to the so-called King's Chamber and the empty and undecorated sarcophagus in this otherwise totally barren and totally uninscribed room. At first this consensus appears convincing, but for the troublesome fact that there are two other chambers in the pyramid: the so-called Queen's Chamber, which lies some 21 meters (69 feet) beneath the King's Chamber, and also the so-called subterranean chamber that is 20 meters (66 feet) beneath the pyramid's base and cuts into the living rock. At a loss to explain why three sepulcher chambers would be needed for only one dead king, Egyptologists for a long time had assumed that the subterranean chamber and the Queen's Chamber were abandoned and that the ancient architect had for some reason changed his design three times regarding where the burial chamber should be. Today this abandonment theory has itself been abandoned. Most modern architects and construction engineers believe the entire monument was constructed according to a well-established plan, which was executed without any major alterations. There is, too, the nagging fact that no mummy or corpse was ever found in the Great Pyramid or, for that matter, in any other royal pyramid in Egypt. True, many pyramids contained empty sarcophagi, but this does not necessarily mean that these sarcophagi were meant for dead bodies. They could easily have served a ritual function rather than a practical function as coffins. Perhaps the most convincing fact that the Great Pyramid was not a tombâor at least, not only a tombâis that its design contains detailed and accurate astronomical and mathematical data that, if properly understood and decoded, seem to suggest a completely different message than that claimed by Egyptologists.

Figure 6.2. The Great Pyramid of Giza's subterranean passage and internal platform aligned to the North Star, Vega, and to Sirius at Zep Tepi. The star shafts built into the upper portions of the completed pyramid aligned to the same and related stars during the Old Kingdom fourth dynasty.

Returning to the question of the date of Zep Tepi and the internal design of the Great Pyramid, the fact that the southern shaft of the Queen's Chamber was aimed at Sirius about 2500 BCE, when the star was at 39.5 degrees and was at essentially 0 degrees in the centuries around 12,200 BCE, when it rested on the horizon as seen from Giza, and the fact that the cycles of Sirius were used by the pyramid builders for both long-term and short-term calendric computations justifies a surmise that the horizontal passage leading to the Queen's Chamber was intended to mark the 0-degree altitude of Sirius at its southern culmination. If the Great Pyramid was designed to symbolize one thing, it is, without question, the sky vaultâfor the perimeter of the pyramid's square base relative to its height represents the same ratio as the circumference of a circle to its radius. We are to think of the Great Pyramid, therefore, not as a pyramid at all, but as a symbolic hemisphere or as a reduced model of the hemispherical sky vault above it.

The southern shaft in the Queen's Chamber invites us to consider two altitudes of the star Sirius, one at 39.5 degrees and the other at 0 degrees, thus determining two dates: 2500 BCE, which is probably the actual construction date of the pyramid, and 12,000 BCE, which represents a date in the remote past that has to do with the beginning or first time of the ancient Egyptians' history defined with calendrical computations of the Sothic cycle and precession cycle of the star Sirius. But is there confirming evidence of such long-term date reckoning in Egyptian pyramid designs?

Figure 6.3. Sirius culminated south so that it just met the horizonâas seen from the latitude of the Great Pyramid at Giza.