Black Gold of the Sun

Read Black Gold of the Sun Online

Authors: Ekow Eshun

Black Gold of the Sun

Searching for Home in England and Africa

EKOW ESHUN

Illustrations by Chris Ofili

HAMISH HAMILTON

an imprint of

PENGUIN BOOKS

HAMISH HAMILTON

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London

WC2R 0RL

, England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

M

4

V

3

B

2 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen's Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi â 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany, Auckland 1310, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London

WC2R 0RL

, England

First published 2005

1

Copyright © Ekow Eshun, 2005

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Illustrations copyright © Chris Ofili, 2005

All rights reserved

Without limiting the rights under copyright

reserved above, no part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system,

or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior

written permission of both the copyright owner and

the above publisher of this book

EISBN: 978â0â141â90158â9

For Kobby

Thirty-five thousand feet over the Atlantic â Saturday night on Oxford Street â Boomerang â The night crawlers of Adabraka â Joseph Eshun and the Sugar Babies â An outstanding example of a tragic conflict

Burenyi in Accra â Esi, Elizabeth Taylor and Block O â Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali in Accra â The pierrots of Independence Square â Ants â Joe and Adelaide at the Happy Bar â Joe vanishes â Adelaide alone â The Eshuns depart for London

The exoticism of suburbia â My racist friends â Watching the Black and White Minstrels â Jerry Rawlings's coup â The vanishings â Kodwo as Reed Richards â At the Ghana High Commission

The summer of red, black and green â The discovery of the Gold Coast â The walls of Elmina castle â Inside the male slave dungeon â Through the Door of No Return â The troubled life of Jacobus Capitein

The wild spree of Horace de Graft Johnson â Escaping the past â Death and marriage on the Gold Coast â Great-uncle Nana Banyin â The two sons of Joseph de Graft â The Negro Prince of Prussia â The morality of slavery

Busua Beach Resort â Drinking at Zion â Big Men and Small Boys â Mr Prempeh returns to Kumasi â The sermon of Bishop Maxwell-Smith â The mysterious death of Richard Wright â Pursued by nightmares â The face of my killer

The elephants of Mole â Chris Ofili's vision of freedom â Flying ace Alhaji â Bob Marley day in Bolgatanga â Tupac and Osama â Hegel and racial science â The border of Ghana â Inside the slave camp â W. E. B. DuBois and

The Souls of Black Folk

â Kodwo and Black Atlantic Futurism â Sun Ra and the rings of Saturn â The City of London â Caribs' Leap

Thirty-five thousand feet over the Atlantic â Saturday night on Oxford Street â Boomerang â The night crawlers of Adabraka â Joseph Eshun and the Sugar Babies â An outstanding example of a tragic conflict

âWhere are you from?' he said. âNo, where are you

really

from?'

It was the businessman who wanted to know. He'd been slumped beside me with his eyes shut and his mouth open

since we'd left London. As the Boeing 777 dipped towards Accra he heaved himself up straight.

âWhere are you from?' he repeated.

The overhead light glistened off the darkness of his skin. He wiped the film of sweat from his forehead.

I gave him the usual line.

âMy parents are from Ghana, but I was born in Britain.'

In all the times I'd been asked the same question it was still the best answer I'd come up with. It wasn't a lie. It just wasn't the whole truth.

âThen you are coming home, my brother,' he said, leaning across me to empty a miniature of Teacher's Scotch into the plastic glasses on our foldaway tables.

âAkwaba,' he said, raising his glass. âWelcome home.'

As we drained the whisky I thought of all the other ways I could have answered his question.

Where are you from?

I don't know.

That's why I'm on this plane.

That's why I'm going to Ghana.

Because I have no home.

I'd caught the plane that afternoon: a British Airways flight straight down the Greenwich Meridian line from Heathrow to Kotoka airport in Accra.

We'd risen above the clouds and, seated over the wing with the whine of the jet engines in my ears, I'd tried to concentrate on an anodyne movie about a gang of con artists breaking into the vault of a Vegas casino, before

giving up to watch the plane's shadow ripple against the clouds below instead.

At Lagos, the flight made a stopover, and I caught my first glimpse of Africa since childhood. The sun was low and from out of the shadows ground crew in blue overalls hastened across the tarmac. A staircase thunked against the plane's flank. The doors sighed open. Tropical warmth filled the cabin. A stewardess with brittle make-up sprayed gusts of rose-scented insect repellent along the aisle.

âThey treat us like animals,' grumbled the businessman.

A line of passengers in heavy cloth robes joined the plane, haloed with sweat. I compared their faces to mine. I looked as African as they did. But I didn't know how far that affinity stretched. Did it reach beneath the skin or did it end on the surface, in the slant of our eyes and the fullness of our lips?

It was April 2002, and I was thirty-three years old.

I was flying to Ghana to find out what I was made of.

My name is Ekow Eshun. That's a story in itself.

Ekow means âborn on a Thursday'. The Ghanaian pronunciation of it is

Eh-kor

and that would be fine if I'd grown up there instead of London where, to the ears of friends, Ehkor became Echo. Throughout my childhood I was pestered by schoolyard wags who thought it hilarious to call after me in descending volume: âEcho, echo, echo.' It was my first lesson in duality. Who you are is determined by

where

you are.

My parents arrived in London from Ghana in 1963. They

never meant to stay. And even though they have spent most of the past forty years in Britain, Ghana is still their home. When I was a child growing up in London, its sounds and smells pervaded our house. Ghana was there in the hot pepper scent of palm nut soup tickling your nostrils as you entered the house; the highlife songs rising from the stereo; the sound of my mother shouting down a capricious telephone line to her sister in Accra.

But Ghana was their home, not mine. I knew this from experience.

I was born in 1968 in a red-brick terraced house in Wembley, north London. I was the youngest of four children. When I was two my parents moved the family to Ghana. We lived in Accra for three years. In 1974, we returned to London. I was five years old. I didn't plan to go back.

My last sight of the place was a country in meltdown. A military junta had taken power shortly before we left. I remembered long speeches by generals on a black-and-white television. The hourly price rises for a bag of rice. Strikes and shortages and demonstrations. What was there to return to?

I asked myself the question I'd been turning over since I first booked my flight: why make this trip?

During my late twenties I began to feel I couldn't live in London any more. The bigotries of the city weighed down on me. I saw condescension in the eyes of bank clerks and malign intent in the store detectives watching me from the end of an aisle. Lynch mobs chased me

through my dreams. I fantasized about taking a machine gun to the streets.

From the extremity of my mood, I guessed that something more fundamental was at work than disaffection with the city. I knew my state of mind wasn't good. My fantasies were getting more violent. I needed to heal myself. I started to think about a childhood spent in London, then Ghana, then London again. Had I lost a part of myself in that toing and froing? Maybe by returning to Ghana I could become whole again.

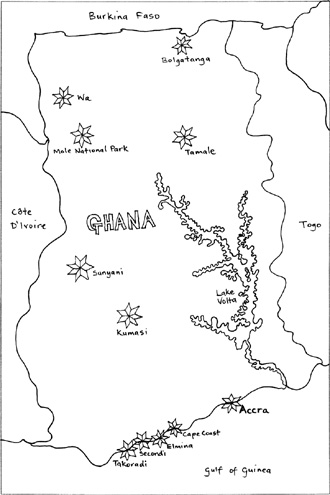

Even though my roots were in Britain it was a white country, and I'd felt like an outsider there all my life. In Ghana I'd be another face in the crowd. Anonymity meant the freedom to be myself, not the product of someone else's prejudice. I bought a map of the country and studied its cities and rivers. I plotted a trip from the Atlantic coastline in the south to the dry north. I wanted to discover the whole country. I wanted to call it home.

I gave myself five weeks. I'd spend the first two exploring Accra, the capital. After that I'd travel west along the shoreline to Elmina, the town where Europeans first settled on African land in 1482. Then I could visit the neighbouring town of Cape Coast, Ghana's former capital, where my parents both grew up. That would take another week. In the remaining fortnight, I'd start heading north. I'd go to Kumasi, capital of the old Asante empire, in Ghana's central region. Then I'd keep going all the way through the arid northern plains until I reached the border with Burkina Faso.

By the time I was ready to go it was 2002 â twenty-eight years since I'd left the country as a child. I was looking for an antidote to London. I wasn't sure if that was too much to ask. All I knew was that if Ghana didn't live up to my hopes I'd have nothing left to hold on to. Then I really would be lost.

From Lagos the Boeing skirted the African coast.

I peered at the Atlantic, 35,000 feet below. This ocean had once been scattered with tall ships. Sails taut they had fought their way to Africa from Venice, Portugal and other states of Europe. Against the force of the northern trade winds masts had snapped. Boats had sunk. Men brave and timid had died. When they eventually succeeded in the fifteenth century it was no less an accomplishment than crossing the Sahara or traversing the Arctic. On 19 January 1482, a Portuguese fleet carrying 600 soldiers, masons and carpenters, holds filled with numbered blocks of granite, weighed anchor on the Ghanaian shoreline. At the town of Elmina they built São Jorge castle, the first permanent European settlement in Africa.