Black Sea (4 page)

Authors: Neal Ascherson

In Yalta, next morning, the hotel staff and the coach driver and the Ukrainian interpreter all evaded our eyes. The television in the foyer, which had been working the day before, was now out of order.

Puzzled, we boarded the coach to visit Bakhchiserai, the old capital of the Crimean Tatars, and after a few miles on the road our guides told us. Mr Gorbachev had been taken suddenly ill. A Committee of National Salvation had been established to exercise his powers; it included Gennadi Yanayev, the Vice-President, Vladimir Kryuchkov, head of the KGB, and General Dimitri Yazov, minister of defence. A proclamation had been issued, stressing certain errors and distortions in the application of

perestroika.

They thought that a state of emergency existed, at least in the Russian Republic if not in Ukraine (to which Crimea belonged).

Now I remembered the ambulance guarding the crossroads at Foros and the men standing about. Illness? Nobody among us believed that. But everybody in the coach, and everyone we were to meet that day, believed in the force of what had happened, and to that they knelt down in homage, whatever their private emotions might be. The interval of liberty, that faltering experiment in openness and democracy called

glasnost,

was over. Nobody in Crimea, neither the officials in the provincial capital of Simferopol nor the holiday crowds at Yalta setting out on their morning pilgrimage to the shingle beaches, supposed that the coup might be reversed or resisted. The Crimean newspapers contained only the rambling proclamations of the Committee, without comment. On the coach, the radio by the driver was out of order too.

I sat back and reflected. Would the airports be closed? We were delegates from the World Congress of Byzantinologists which had just taken place in Moscow, and we were near the end of a post-Congress tour of historic sites in Crimea. The biggest group on the coach was Genoese - historians, archivists and journalists. They had come with their families to see the ruins of their city's mediaeval trading empire along the northern Black Sea shore. Now they grew animated, then uproarious. To live through genuine barbarian upheavals on the fringe of the known world seemed to them another way of following in their ancestors' footsteps.

The coach ran through the little beach resort of Alushta and turned inland towards the mountain pass leading to Simferopol. I tried to imagine the panic in the world outside, the cancelled lunches and emergency conclaves at

nato

in Brussels, the solemn crowds which would be gathering in the Baltic capitals to resist with songs and sticks the return of the Soviet tank armies. There might, I thought, be a few demonstrations in Russian cities; some devoted boy might try to burn himself alive in Red Square. But the putsch -as an act of force - seemed to me decisive. I had seen something like it ten years before, in

1981,

when martial law was declared in Communist Poland. That blow had proved irresistible. So, I assumed, would this one.

At that moment in the summer of

1991,

the Soviet Union still overshadowed the whole of northern Eurasia from the Pacific to the Baltic. The outside world still believed almost blindly in the reforming genius of Mikhail Gorbachev, and few foreigners as yet understood, or even wanted to understand, that Gorbachev's ambitious programme

oiperestroika

structural reform had come to nothing. They could not grasp that his personal following among the ruling oligarchy of the Soviet Union had leaked away during the previous year, nor that the Communist Party - the only effective executive instrument in the land - was now refusing to go further with the political changes which were dismantling its own monopoly of power, nor that the military and police commanders had begun to disobey their orders and act on their own initiative, nor that Gorbachev was no longer respected or even liked by the Russian people.

It was only because I had spent the previous week talking to Russian friends and foreign journalists in Moscow that I had begun to realise how serious Gorbachev's failure was. The phase of reformed, liberalised Communism was over. And the illusion that plural democracy and free-market economy could be simply ordered into existence by the Kremlin - that had collapsed too. But at the same time I knew that this putsch in Moscow could solve nothing. The way ahead was blocked, certainly. And yet the way back offered by Gennadi Yanayev and his fellow-conspirators — a reversion to police tyranny and imperial reconquest — also led nowhere. In the longer term, the plotters had only ensured an even steeper descent into chaos and decay for the Soviet state. But in the short term, I was convinced, they had succeeded and they would be obeyed.

In the palace of the Tatar khans at Bakhchiserai - unloved and faded -1 caught the glance of a Russian woman in charge of a band of girl students. It was a dark, hot glance; she halted her girls by pulling roughly on their yellow plaits, as if on a train's alarm cord, and came over to talk. This morning, I have two thoughts,' she began. The first is for my son, who is in Germany: now I shall never see him again. The second is that there is no vodka in the shops, so I have no way to forget what is happening. You are from Britain? May we please export to you some of our big surplus of fascists?'

Beside us, a fountain carved with a marble eye wept tears of cool spring-water, mourning for a slave-girl who died before she could learn to love the Tatar khan. Alexander Pushkin, touched by the legend, first floated a rose in the basin of the fountain, and they still put fresh roses there for the tourists. All about us I saw Russians uncomfortably looking away. They did not understand our words, but they recognised our tone of voice: a dangerous one. A holiday had ended that morning with the news on the radio, and the season of prudence had returned. Only the students watched us with their round blue eyes, heads cocked, indifferent as birds.

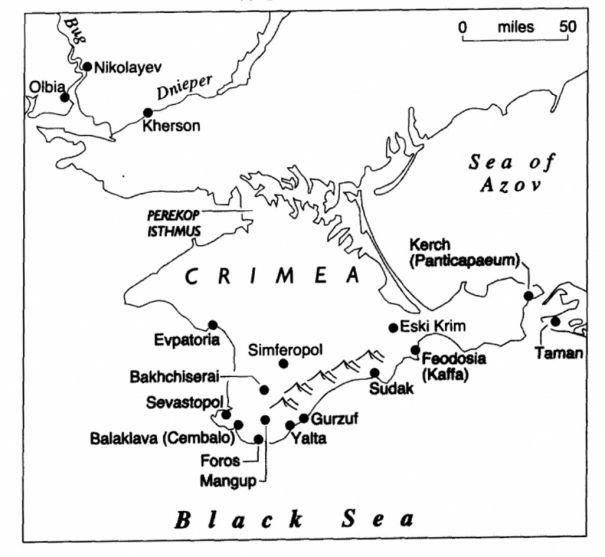

Crimea is a big brown diamond. It is connected to the mainland only by a few strings of isthmus and sand-spit, by a natural land causeway at Perekop on the west and by watery tracks across the Sivash salt-lagoons on the north and east. In history, Crimea consists of three zones: mind, body and spirit.

The zone of mind is the coast — the chain of colonial towns and port-cities along the Black Sea margin. For nearly three thousand years, with interruptions of fire and darkness, people in these cities kept accounts, read and wrote books, enforced planning controls with the aid of geometry, debated literary and political gossip from some distant metropolis, locked one another up in prisons, allotted building land for the temples of mutually hostile cults, regulated advance payments on the next season's orders for slaves.

The Ionian Greeks reached this coast some time during the eighth century BC, and under its steep, forested capes, they set up trading-posts — much like European 'factories' on the Guinea coast of Africa two thousand years later — which grew into towns with stone walls and then into maritime cities. The Roman and Byzantine empires inherited these coastal colonies. Then, in the Middle Ages, the Venetians and the Genoese, licensed by the later Byzantine emperors, revived the zone of the mind, enlarged the Black Sea trade and founded new cities of their own.

In the early thirteenth century, Chingiz ('Genghis') Khan united the Mongolian peoples of east-central Asia and led them out to conquer the surrounding world. China fell, and the Mongol cavalry rode westwards to conquer not only the central Asian cities but the lands which are now Afghanistan, Kashmir and Iran within the next few years. But it was not until

1240—

1, ten years after the death of Chingiz, that a Mongol army led by Batu reached Russia and eastern Europe (where they were mis-named 'Tatars' after another tribe which had once been powerful in central Asia but which Chingiz had exterminated). Batu's cavalry eventually withdrew from east and central Europe without any serious attempt to make their conquests permanent, and settled on the Volga. There the 'Golden Horde', as this western part of the Mongol-Tatar empire came to be known, remained for three centuries after the death of Batu in

1255.

From its capital on the Volga, the Horde controlled both the steppe north of the Black Sea and the Crimean peninsula.

There were times when the Horde burned and looted cities on the Crimean coast. But the Mongol presence also brought those cities

great fortune. There was now a single authority in control of the entire Eurasian plain from the Chinese border in the east to what is now Hungary in the west. With stability in the steppes, long-range trade became possible. Trade routes - the 'Silk Routes' - appeared, reaching from China to the Black Sea by land and from there by sea to the Mediterranean. One route led westwards across the lower Volga to terminate at the Venetian colony of Tana, on the Sea of Azov. Later, in the fifteenth century, another Silk Route opened connecting the Persian provinces of the Mongol empire with the Black Sea at Trebizond.

An end was put to all this transcontinental commerce after 1453, when the Turks finally captured Constantinople and destroyed the remains of the Byzantine Empire around the Black Sea, which was closed to Western voyagers. The cities of the coast were mostly abandoned, and their ruins were covered by the dry red earth and the mauve herbs of the Crimean steppe. The coast of Crimea did not begin to revive until the eighteenth century, when the Russian Empire reached the Black Sea, and that revival took a new variety of urban forms. Chersonesus was rebuilt as the naval base of Sevastopol, Yalta as a seaside resort, Kaffa as the grain port of Feodosia.

The zone of the body in Crimea is the inland steppe country, behind the coastal mountains. It is not flat, but a plateau landscape of greyish-green downs, trapezoid and eroded. Its skin is a dry turf woven of sharp-smelling herbs, and if you cut the skin the earth leaks out and blows away in the east wind.

Along the coast, the wind comes off the Black Sea or, very suddenly, in harrying squalls down from the mountains. But inland, behind the mountain ranges, the wind blows steadily out of Asia, across three thousand miles of what used to be level grassland separating Europe from the high Central Asian pastures where the nomad peoples began their journeys. The archaic Greeks crossed a watery ocean to reach Crimea, and their voyage from the Bosporus to southern Russia could take a month or more. But the nomads who came to this coast crossed an ocean of grass, sailing slowly onwards for months and years in their wagons, preceded by their herds of cattle and horses, until they came to rest up against the Crimean hills and the sea beyond them.

The Scythians were already here on the Crimean steppe and the inland plains when the Greeks first came ashore in the eighth century BC. In the centuries which followed, the period of Greek colonisation, the pressure of westward migration out of central Asia was weak, and five hundred more years passed before the Scythians resumed their westward journey and were replaced by the Sarmatians. Then, in the first centuries of our era, the push of one nomad nation upon another became much more urgent. After the Sarmatians came the Goths, from the north, and then the all-destroying Huns, and then the Khazars who formed their briefly stable steppe empire on the Black Sea shores in the eighth century AD. Turkic-speaking nomads (called variously Kipchak, Cuman or Polovtsy) held the steppe between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries, and were then overrun or driven further west by the oncoming Mongol-Tatars of the Golden Horde.

The Golden Horde's capital was far away from the Black Sea coast, at Saray on the middle Volga. The Horde was always a loose polity which soon began to pull apart, and in the fifteenth century a southern branch of the Horde set up its own independent kingdom on the inland plains of Crimea, settling down to intensive farming and stock-breeding and gradually abandoning the old pastoral life. This was the Crimean Tatar khanate, or 'Crim Tartary'. A few centuries of relative calm ensued in Crimea until the Ottoman Empire, after the capture of Constantinople, reached the northern shore of the Black Sea and Crimea itself. For the Crimean Tatars, who had converted to Islam in the fourteenth century, Turkish domination meant a mere change of allegiance rather than displacement, and the khanate survived until Catherine the Great conquered Crimea for the Russian Empire in 1783.