Black Swan Green (34 page)

Authors: David Mitchell

Some trailers were parked in the Danemoor Farm lay-by, despite the hill of gravel left there to ward off gypsies. They hadn’t been there this morning. But this morning belonged to a different age.

‘Come over on Saturday anyway, if yer want. Mum’ll cook yer lunch. It’ll be a right laugh.’

Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday had to be got through first. ‘Thanks.’

Ross Wilcox and his lot’d streamed off the bus first without even a glance at me. I crossed the village green thinking the worst of this turd of a day was over.

‘Where d’

you

think you’re going, Maggot?’ Ross Wilcox, under the oak tree with Gary Drake, Ant Little, Wayne Nashend and Darren Croome. They’d’ve loved me to make a run for it. I didn’t. Planet Earth’d shrunk to a bubble five paces wide.

‘Home,’ I said.

Wilcox flobbed. ‘Ain’t yer go-go-go-going to t-t-talk to us?’

‘No thanks.’

‘Well, yer ain’t

goin’

to yer poncy fuckin’ home down poncy fuckin’ Kingfisher Meadows yet, yer poncy fuckin’

maggot

.’

I let Wilcox make the next move.

He didn’t. It came from behind. Wayne Nashend pinned me in a full nelson. My Adidas bag was ripped out of my hand. No point in shouting ‘That’s my bag!’ We all knew that. The

crucial

thing was to not cry.

‘Where’s yer bumfluff, Taylor?’ Ant Little peered at my upper lip. ‘Ain’t yer got any bumfluff left?’

‘I shaved it off.’

‘“I shaved it off”’ Gary Drake mimicked me. ‘That s’posed to impress us?’

‘There’s this joke going round, Taylor,’ said Wilcox. ‘Have yer heard it? “D’yer know Jason Taylor?”’

‘“N-n-n-o,”’ replied Gary Drake. ‘“B-b-but I t-trod in s-s-some once!”’

‘Yer’re a

laughing-stock

, Taylor,’ spat Ant Little. ‘A piss-flaps toss-pot

laughing-stock

!’

‘Going to the pictures with your

mummy

!’ said Gary Drake. ‘You don’t deserve to

live

. We should

hang

you from this tree.’

‘Say somethin’, then,’ Ross Wilcox came right up close, ‘

Maggot

.’

‘Your breath smells really bad, Ross.’

‘

What?

’ Wilcox’s face arseholed up. ‘

WHAT?

’

I’d shocked myself, too. But there was no going back. ‘I’m not trying to be insulting, honest. But your breath reeks. Like a bag of ham. Nobody tells you ’cause they’re scared of you. But you should clean your teeth more often or eat mints ’cause it’s

chronic

.’

Wilcox let a moment drag by.

A sharp double-slap crushed my jaw.

‘Oh, and you’re saying yer

not

scared of me?’

Pain is a good focuser. ‘It could be halitosis. The chemist in Upton could give you something for it, if it is.’

‘I could kick your

head in

, you dickless

twat

!’

‘Yeah, you could. All five of you.’

‘

On my fuckin’ own!

’

‘I’m not doubting it. I saw you fight Grant Burch, remember.’

The school bus was still by the Black Swan. Norman Bates sometimes gives a bundle to Isaac Pye and Isaac Pye gives Norman Bates a brown envelope. Not that I was expecting any help.

‘This – oily – spacko –

maggot

’ – Ross Wilcox jabbed my chest with each word – ‘needs – a –

GRUNDY

!’ A grundy’s where a bunch of kids yank you up, hard, by your underpants. Your feet leave the ground and the crotch of your pants is forced up your bum-crack so your balls and dick get crushed.

So a grundying’s exactly what I got.

But grundies’re only fun if the victim squeals and tries to fight. I steadied myself on Ant Little’s head and sort of rode it out. Grundies humiliate rather than hurt. My attackers pretended to find it funny, but it was heavy, unrewarding work. Wilcox and Nashend trampolined me up and down. My pants just burnt my crotch rather than split me in two. I was dropped on to the soaking grass.

‘That,’ promised Ross Wilcox, panting, ‘is just for

starters

.’

‘M

aaaaaa

ggot!’ Gary Drake sang out of the mist by the Black Swan. ‘Where’s your bag?’

‘Yeah.’ Wayne Nashend booted my arse as I got up. ‘Better find it.’

I sort of hobbled towards Gary Drake, my bumbone smarting.

The school bus revved up. Its gears cranked.

Grinning this sadistic grin, Gary Drake swung my Adidas bag.

Now I saw what was coming and broke into a run.

Tracing a perfect arc, my Adidas bag landed on the roof of the bus.

The bus jerked into motion, off to the crossroads by Mr Rhydd’s.

Changing course, I sprinted through the long wet grass,

prayed

the bag’d slide off.

Laughter acker-ack-acked after me, like machine guns.

One ½ p of luck rolled my way. A combine harvester’d made a slow traffic jam from Malvern Wells. I managed to reach the school bus while it waited at the crossroads by Mr Rhydd’s shop.

‘

What

,’ snarled Norman Bates as the door opened, ‘d’you think you’re

playing

at?’

‘Some boys,’ I fought for breath, ‘chucked my bag on the roof.’

The kids still on the bus lit up with excitement.

‘

What

roof?’

‘The roof of your bus.’

Norman Bates gave me a look like I’d shat in his bap. But he swung down, nearly knocking me over, marched to the end of the bus, climbed up the back-end monkey ladder, grabbed my Adidas bag, lobbed it at me, and climbed back down to the road. ‘Yer mates’re a bunch o’ wankers, Sunbeam.’

‘They’re not my mates.’

‘Then why let ’em push you around?’

‘I don’t

let

them. There’s five of them. Ten of them. More.’

Norman Bates sniffed. ‘But only one King Turd. Right?’

‘One or two.’

‘One’ll do. What yer need is one of these little beauties.’ A

lethal

Bowie knife suddenly rotated in front of my eyes. ‘Sneak up on King Turd,’ Norman Bates’s voice softened, ‘and

slice

–

his

–

tendons

. One slit, two slit, tickle him under there. If he fucks around with you after that, just puncture the tyres on his wheelchair.’ Norman Bates’s knife disappeared into thin air. ‘Army and Navy Surplus Stores. Best tenner you’ll ever spend.’

‘But if I sliced Wilcox’s tendons, I’d get sent to borstal.’

‘Well, wakey

fucking

wakey, Sunbeam!

Life

’s a borstal!’

Autumn’s fungusy, berries’re manky, leaves’re rusting, Vs of long-distance birds’re crossing the sky, evenings’re smoky, nights’re cold. Autumn’s nearly dead. I hadn’t even noticed it was ill.

‘I’m back!’ Every afternoon I yell it, just in case Mum or Dad’d come home early from Cheltenham or Oxford or wherever.

Not that there’s ever a reply.

Our house is

bags

emptier with Julia gone. Her and Mum drove up to Edinburgh two weekends ago. (Julia passed her driving test. First time, of course.) She’d spent the second half of the summer with Ewan’s family in the Norfolk Broads, so you’d think I’d’ve had time to get used to sisterlessness. But it’s not just the person who fills a house, it’s their

I’ll be back later!

s, their toothbrushes and not-being-used-right-now hats and coats, their belongingnesses. Can’t

believe

I miss my sister this much, but I do. Mum and Julia left first thing ’cause Scotland’s a day away by car. Dad and me waved her off. Mum’s Datsun’d turned into Kingfisher Meadows, when it stopped. Julia jumped out, opened the boot, ferreted through her box of records and ran back up the drive. She thrust her

Abbey Road

LP into my hands. ‘Look after this for me, Jace. It’ll only get scratched if I take it to halls.’ She hugged me.

I still smelt Julia’s hair lacquer, even after the car’d gone.

The pressure cooker sat on the cooker, leaked stewing-steak fumes. (Mum starts it off in the morning so it cooks all day.) I made a grapefruit Quash and risked scoffing the last Penguin biscuit ’cause there was nothing else in the tin but Ginger Nuts and Lemon Puffs. I went upstairs to change out of my school uniform. Waiting in my room was the first of the three surprises.

A TV. Sitting on my desk. It hadn’t been there this morning.

FERGUSON MONOCHROME PORTABLE TELEVISION,

said its badge.

MADE IN ENGLAND.

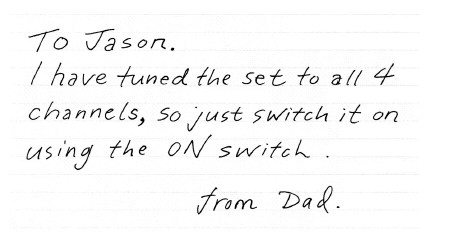

(Dad says if we don’t buy British all the jobs’ll go to Europe.) Brand-new shine, brand-new smell. An office envelope with my name on it stood propped up. (Dad’d written my name in 2H pencil so the envelope can be reused.) Inside was a file card, written in green Biro.

Why?

I was pleased, for sure. In 3KM only Clive Pike and Neal Brose’ve got TVs in their bedrooms. But why now? My birthday isn’t till January. Dad

never

gives things like this for no reason, not just out of the blue. I switched the TV on, lay on my bed and watched

Space Sentinels

and

Take Hart

. Watching TV on your bed shouldn’t be odd, but it somehow is. Like eating oxtail soup in the bath.

TV deadens worrying about school, a bit. Dean was ill today so the seat on the school bus next to me was empty. Ross Wilcox took it, acting all matey to remind me we’re not. Wilcox kept on at me to get out my pencil case. ‘G-g-go on, l-l-l-lend us yer p-p-protractor, T-t-taylor, honest, I want to do m-my m-m-m-maths homework.’ (I

don’t

stammer that badly. Mrs de Roo says we’re making real progress.) ‘Got a sh-sh-sharpener, T-t-taylor?’

‘No’, I kept saying, flat and bored. ‘No.’ The other day he got hold of Floyd Chaceley’s pencil case in the maths room and tipped its contents into the Quad.

‘What d’yer mean, n-n-no? What d’yer do when your p-p-pencils get b-b-blunt?’ Question after needling question, that’s the Wilcox Method. Answer, and he’ll twist your reply so that it seems only a total twat could’ve said what you just said. Don’t answer, and it’s like you’re admitting it’s okay for Wilcox to be ripping into you. ‘S-s-so d-d-d-do girls find your s-s-s-stutter s-s-s-sexy, T-t-taylor?’ Oswald Wyre and Ant Little do this jackal laughter like their master’s all six Monty Pythons rolled into one comedy thug. Wilcox’s power is that you think it’s not him speaking but public opinion judging you through him. ‘B-b-b-bet it m-m-m-makes ’em fizz in their p-p-p-p-per-per-pah-pah-pi-pi-poo-poo-poo-panties!’

Two rows in front, Squelch suddenly vommed back up a party-sized tube of Smarties he’d wolfed to win a go on Ant Little’s Space Invaders calculator. A tide of multi-coloured vomit advancing up the aisle was enough to distract Wilcox. I got off at Drugger’s End and went round the back of the village hall and over the Glebe, alone. It takes a while. Over by St Gabriel’s some way-too-early fireworks streaked spoon silver against the Etch-a-Sketch grey sky. Someone’s older brother must’ve bought them from Mr Rhydd’s. I was still too poisoned by Wilcox to pick the last watery blackberries of 1982.

Was it the same poison that spoilt Dad’s incredible present?

John Craven’s Newsround

was about the

Mary Rose

. The

Mary Rose

was Henry VIII’s flagship that sank in a storm four centuries ago. It was lifted out of the sea bottom recently. All England was watching. But the silty, drippy, turdy timbers lugged up by the floating cranes look nothing like the shining galleon in the paintings. People’re now saying the money should’ve been spent on hospital beds.

The doorbell rang.

‘Chilly day,’ rasped an old man in a tweed cap. ‘Nip in the air.’ The man was today’s second surprise. His suit had no obvious colour.

He

had no obvious colour, come to that. I’d put on the the door chain ’cause Dad says not even Black Swan Green’s safe from perverts and maniacs. The chain amused the old man. ‘Crown jewels you’ve got stashed away in there, then, is it, eh?’

‘Erm…no.’

‘Ain’t goin’ to huff and puff and blow yer house down, yer know. Lady of the house at home, by any chance?’

‘Mum? No. She’s working in Cheltenham.’

‘A shame that is. Year back, I grinded her knives sharp as

razors

but no doubt they’ll be blunt again by now. A blunt knife is the most dangerous knife, yer know that? Any doctor’ll tell yer as much.’ His accent skimmed and skittered. ‘Blunt blades slip fierce easy. She’ll be back soon, will she?’

‘Not till seven.’

‘Pity, pity, don’t know when I’ll be passin’ here again. How ’bout yer fetchin’ them knives now, and I’ll make ’em nice and sharp anyway, eh? To surprise her, like. Got my stones and my tools.’ He thumped a lumpy kitbag. ‘Shan’t take no more’n a second. Yer mam’ll be

that

pleased. The best son in the Three Counties, she’ll call yer.’

I doubted that very much. But I don’t know how you get rid of knife grinders. One rule says you mustn’t be rude. Just shutting the door on him’d’ve been rude. But another rule says Never Talk to Strangers, which I was breaking. Rules should get their stories straight. ‘I’ve only got my pocket money, so I couldn’t afford—’

‘Cut yer a deal, my

chavvo

. I like a lad who keeps his manners about him. “Manners do maketh the man.” A proper clever haggler, yer mam’ll call yer. Tell us how much pocket money’s in yer piggy bank, and I’ll tell yer how many knives I can do for what yer got.’

‘Sorry.’ This was getting worse. ‘I’d best ask Mum first.’

The knife grinder’s look was friendly on the surface. ‘

Never

cross the womenfolk! Still, I’ll see if I can’t call this way in a day or two after all. Unless the

squire

o’ the manor’s at home, that is, by any chance?’

‘Dad?’

‘Aye, Dad.’

‘He won’t be back till…’ You never know these days. Often he calls to say he’s stuck in a motel somewhere. ‘Late.’

‘If he isn’t fierce worried about his driveway,’ the knife grinder tilted his head and sucked air, ‘he needs to be. Tarmac’s cracked serious, like. Pack of tinkers laid it originally, that’s my guess. Rain’ll freeze inside them cracks come winter, prise the tarmac up, see, and by spring it’ll be like the moon! Needs tearin’ up and re-layin’

proper

. Me and my brother’ll get it done faster than—’ (His finger-click was as loud as the popper in

Frustration

.) ‘Tell yer dad from me, will yer do that?’

‘Okay.’

‘Promise?’

‘I promise. I could take your phone number.’

‘Telephones?

Liar

phones, I call ’em. Eye to eye’s the only way.’

Knife Grinder heaved up his kitbag and walked down the drive. ‘Tell yer dad!’ He knew I was watching. ‘A promise is a promise,

mush

!’

‘How generous of him,’ was what Mum said when I told her about the TV. But how she said it was sort of chilling. When I heard Dad’s Rover get home I went out to the garage to thank him. But instead of looking pleased he just mumbled, a bit embarrassed, no, almost like he was sorry about something, ‘Glad it meets with your approval, Jason.’ Only when Mum dished up the stew did I even remember the knife grinder’s visit.

‘Knife grinding?’ Dad forked off some gristle to one side. ‘That’s a gypsy scam, old as the hills. Surprised he didn’t get his Tarot cards out, there on the porch. Or start scavving for scrap metal. If he comes back, Jason, shut the door on him.

Never

encourage those people. Worse than Jehovah’s Witnesses.’

‘He said he might,’ now

I

felt guilty for making that promise, ‘come back to talk about the driveway.’

‘What

about

the driveway?’

‘It needs retarmacking. He said.’

Dad’s face’d turned thundery. ‘And that makes it true, does it?’

‘Michael,’ Mum said, ‘Jason’s just reporting a conversation.’

Beef gristle tastes like deep-seam phlegm. The only real live gypsy I ever met was a quiet kid at Miss Throckmorton’s. His name’s gone now. He must’ve skived off most days ’cause his empty desk became a sort of school joke. He wore a black jumper instead of green and a grey shirt instead of white, but Miss Throckmorton never once did him up for it. A Bedford truck used to drop him off at the school gates. In my memory that Bedford truck’s as large as the whole school. The gypsy kid’d jump down from the cabin. His dad looked like Giant Haystacks the wrestler, with tattoos snaking up his arms. Those tattoos and the glance he shot round the playground made sure

no one

, not Pete Redmarley, not even Pluto Noak,

thought

about picking on the gypsy kid. For his part, the gypsy kid sat under the cedar sending out

piss off

waves. He didn’t give a toss about Kick-the-Can or Stuck-in-the-Mud. One time, he was at school for a rounders match and he whacked the ball clean over the hedge and into the Glebe. He just strolled round the posts with his hands in his pockets. Miss Throckmorton had to put him in charge of scoring ’cause we ran out of rounders balls. But when we next looked at the scoreboard he’d gone.

I blobbed HP sauce into my stew. ‘Who

are

gypsies, Dad?’

‘How do you mean?’

‘Well…where did they live originally?’

‘Where do you think the word “gypsy” is from? E

gyp

tian.’

‘So gypsies’re African?’

‘Not now, no. They migrated centuries ago.’

‘Why don’t people like them?’

‘Why

should

decent-minded citizens like layabouts who pay nothing to the state and flout every planning regulation in the book?’

‘

I

think,’ Mum sprinkled pepper, ‘that’s a harsh assessment, Michael.’

‘You wouldn’t if you’d ever met one, Helena.’

‘This knife grinder chap made an

excellent

job of the scissors and knives, last year.’

‘Don’t tell me,’ Dad’s fork stopped in mid-air, ‘you

know

this man?’

‘Well,

a

knife grinder’s been coming to Black Swan Green every October for years. Couldn’t be

sure

if it’s the same one without seeing him, but I’d imagine he probably is.’

‘You’ve actually given this beggar

money

?’

‘Do

you

work for nothing, Michael?’

(Questions aren’t questions. Questions’re bullets.)

Dad’s cutlery clinked as he put it down. ‘You kept this…

transaction

hushed up for a whole year?’

‘“Hushed up”?’ Mum did a silent

huh

of strategic shock. ‘You’re accusing me of “hushing up”?’ (That made my guts quease. Dad flashed Mum this

Not in front of Jason

look. That made my guts quease and shudder.) ‘Doubtless I didn’t want to clutter your executive day with trivial housewifery.’

‘And how much,’ Dad wasn’t backing off, ‘did this vagrant rip you off for?’

‘He asked for one pound and I paid it. For sharpening

all

the knives, and a jolly good job he made of them. One pound. A penny more than one of your frozen Greenland pizzas.’

‘I can’t believe you fell for this gypsy-shire-horses-painted-wagons-jolly-old-England hokum. For God’s sakes, Helena. If you want a knife sharpener buy one from an ironmonger’s. Gypsies

are

work-shy hustlers and once you give them an

inch

, a horde of his cousins’ll be beating a path back to your door till the year 2000. Knives, crystal balls and tarmacking today, and car-stripping, raids on garden sheds, flogging stolen goods tomorrow.’

Their arguments’re speed chess these days.

I’d finished. ‘Can I get down now, please?’