Blandings Castle and Elsewhere

Read Blandings Castle and Elsewhere Online

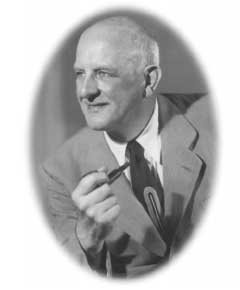

Authors: P. G. Wodehouse

The author of almost a hundred books and the creator of

Jeeves, Blandings Castle, Psmith, Ukridge, Uncle Fred and

Mr Mulliner, P.G. Wodehouse was born in 1881 and educated

at Dulwich College. After two years with the Hong

Kong and Shanghai Bank he became a full-time writer,

contributing to a variety of periodicals including

Punch

and the

Globe.

He married in 1914. As well as his novels

and short stories, he wrote lyrics for musical comedies

with Guy Bolton and Jerome Kern, and at one time had

five musicals running simultaneously on Broadway. His time in

Hollywood also provided much source material for fiction.

At the age of 93, in the New Year's Honours List of 1975,

he received a long-overdue knighthood, only to die

on St Valentine's Day some 45 days later.

Some of the P. G. Wodehouse titles to be published

by Arrow in

2008

JEEVES

The Inimitable Jeeves

Carry On, Jeeves

Very Good, Jeeves

Thank You, Jeeves

Right Ho, Jeeves

The Code of the Woosters

Joy in the Morning

The Mating Season

Ring for Jeeves

Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit

Jeeves in the Offing

Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves

Much Obliged, Jeeves

Aunts Aren't Gentlemen

UNCLE FRED

Cocktail Time

Uncle Dynamite

BLANDINGS

Something Fresh

Leave it to Psmith

Summer Lightning

Blandings Castle

Uncle Fred in the Springtime

Full Moon

Pigs Have Wings

Service with a Smile

A Pelican at Blandings

MULLINER

Meet Mr Mulliner

Mulliner Nights

Mr Mulliner Speaking

GOLF

The Clicking of Cuthbert

The Heart of a Goof

OTHERS

Piccadilly Jim

Ukridge

The Luck of the Bodkins

Laughing Gas

A Damsel in Distress

The Small Bachelor

Hot Water

Summer Moonshine

The Adventures of Sally

Money for Nothing

The Girl in Blue

Big Money

P.G.WODEHOUSE

... AND ELSEWHERE

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

ISBN 9781409063568

Version 1.0

Published by Arrow Books 2008

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Copyright by The Trustees of the Wodehouse Estate

All rights reserved

This electronic book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

First published in the United Kingdom in 1935 by Herbert Jenkins Ltd

Arrow Books

The Random House Group Limited

20 Vauxhall Bridge Road, London, SW1V 2SA

Addresses for companies within The Random House Group Limited

can be found at:

www.randomhouse.co.uk/offices.htm

The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

ISBN: 9781409063568

Version 1.0

Blandings Castle

...AND ELSEWHERE

E

XCEPT

for the tendency to write articles about the Modern

Girl and allow his side-whiskers to grow, there is nothing an

author to-day has to guard himself against more carefully than

the Saga habit. The least slackening of vigilance and the thing

has gripped him. He writes a story. Another story dealing with

the same characters occurs to him, and he writes that. He feels

that just one more won't hurt him, and he writes a third. And

before he knows where he is, he is down with a Saga, and no cure

in sight.

This is what happened to me with Bertie Wooster and Jeeves,

and it has happened again with Lord Emsworth, his son Frederick, his butler

Beach, his pig the Empress and the other residents of Blandings Castle. Beginning

with

S

OMETHING

F

RESH

,

I went on to

L

EAVE

I

T TO

P

SMITH

,

then to

S

UMMER

L

IGHTNING

,

after that to

H

EAVY

W

EATHER

,

and now to the volume which you have just borrowed. And, to show the habit-forming

nature of the drug, while it was eight years after

S

OMETHING

F

RESH

before the urge for

L

EAVE

I

T TO

P

SMITH

gripped me, only eighteen

months elapsed between

S

UMMER

L

IGHTNING

and

H

EAVY

W

EATHER

.

In a word, once a man who could take it or leave it alone, I had become an

addict.

The stories in the first part of this book represent what I may

term the short snorts in between the solid orgies. From time to

time I would feel the Blandings Castle craving creeping over me,

but I had the manhood to content myself with a small dose.

In point of time, these stories come after

L

EAVE

I

T TO

P

SMITH

and before

S

UMMER

L

IGHTNING

.

P

IG-HOO-O-O-O-EY

,

for example, shows Empress of Blandings winning her first silver medal in

the Fat Pigs class at the Shropshire Agricultural Show. In

S

UMMER

L

IGHTNING

and

H

EAVY

W

EATHER

she is seen struggling to repeat in the following year.

T

HE

C

USTODY OF THE

P

UMPKIN

shows Lord Emsworth passing through the brief

pumpkin phase which preceded the more lasting pig seizure.

And so on.

Bobbie Wickham, of

M

R

P

OTTER

T

AKES A

R

EST

C

URE

,

appeared in three of the stories in a book called

M

R

M

ULLINER

S

PEAKING

.

The final section of the volume deals with the secret history

of Hollywood, revealing in print some of those stories which are

whispered over the frosted malted milk when the boys get

together in the commissary.

P. G. WODEHOUSE

T

HE

morning sunshine descended like an amber shower-bath

on Blandings Castle, lighting up with a heartening glow its

ivied walls, its rolling parks, its gardens, outhouses, and messuages,

and such of its inhabitants as chanced at the moment

to be taking the air. It fell on green lawns and wide terraces, on

noble trees and bright flower-beds. It fell on the baggy trousers-seat

of Angus McAllister, head-gardener to the ninth

Earl of Emsworth, as he bent with dour Scottish determination

to pluck a slug from its reverie beneath the leaf of a lettuce. It

fell on the white flannels of the Hon. Freddie Threepwood,

Lord Emsworth's second son, hurrying across the water-meadows.

It also fell on Lord Emsworth himself and on

Beach, his faithful butler. They were standing on the turret

above the west wing, the former with his eye to a powerful

telescope, the latter holding the hat which he had been sent to

fetch.

'Beach,' said Lord Emsworth.

'M'lord?'

'I've been swindled. This dashed thing doesn't work.'

'Your lordship cannot see clearly?'

'I can't see at all, dash it. It's all black.'

The butler was an observant man.

'Perhaps if I were to remove the cap at the extremity of the

instrument, m'lord, more satisfactory results might be obtained.'

'Eh? Cap? Is there a cap? So there is. Take it off, Beach.'

'Very good, m'lord.'

'Ah!' There was satisfaction in Lord Emsworth's voice. He

twiddled and adjusted, and the satisfaction deepened. 'Yes, that's

better. That's capital. Beach, I can see a cow.'

'Indeed, m'lord?'

'Down in the water-meadows. Remarkable. Might be two

yards away. All right, Beach. Shan't want you any longer.'

'Your hat, m'lord?'

'Put it on my head.'

'Very good, m'lord.'

The butler, this kindly act performed, withdrew. Lord Emsworth

continued gazing at the cow.

The ninth Earl of Emsworth was a fluffy-minded and amiable

old gentleman with a fondness for new toys. Although the

main interest of his life was his garden, he was always ready to try

a side line, and the latest of these side lines was this telescope of

his. Ordered from London in a burst of enthusiasm consequent

upon the reading of an article on astronomy in a monthly

magazine, it had been placed in position on the previous evening.

What was now in progress was its trial trip.

Presently, the cow's audience-appeal began to wane. It was a

fine cow, as cows go, but, like so many cows, it lacked sustained

dramatic interest. Surfeited after awhile by the spectacle of it

chewing the cud and staring glassily at nothing, Lord Emsworth

decided to swivel the apparatus round in the hope of picking up

something a trifle more sensational. And he was just about to do

so, when into the range of his vision there came the Hon.

Freddie. White and shining, he tripped along over the turf like

a Theocritan shepherd hastening to keep an appointment with a

nymph, and a sudden frown marred the serenity of Lord Emsworth's

brow. He generally frowned when he saw Freddie, for

with the passage of the years that youth had become more and

more of a problem to an anxious father.

Unlike the male codfish, which, suddenly finding itself the

parent of three million five hundred thousand little codfish, cheerfully resolves

to love them all, the British aristocracy is apt to look with a somewhat jaundiced

eye on its younger sons. And Freddie Threepwood was one of those younger sons

who rather invite the jaundiced eye. It seemed to the head of the family that

there was no way of coping with the boy. If he was allowed to live in London,

he piled up debts and got into mischief; and when you jerked him back into

the purer surroundings of Blandings Castle, he just mooned about the place,

moping broodingly. Hamlet's society at Elsinore must have had much the same

effect on his stepfather as did that of Freddie Threepwood at Blandings on

Lord Emsworth. And it is probable that what induced the latter to keep a telescopic

eye on him at this moment was the fact that his demeanour was so mysteriously

jaunty, his bearing so intriguingly free from its customary crushed misery.

Some inner voice whispered to Lord Emsworth that this smiling, prancing youth

was up to no good and would bear watching.

The inner voice was absolutely correct. Within thirty seconds

its case had been proved up to the hilt. Scarcely had his lordship

had time to wish, as he invariably wished on seeing his offspring,

that Freddie had been something entirely different in manners,

morals, and appearance, and had been the son of somebody else

living a considerable distance away, when out of a small spinney

near the end of the meadow there bounded a girl. And Freddie,

after a cautious glance over his shoulder, immediately proceeded

to fold this female in a warm embrace.

Lord Emsworth had seen enough. He tottered away from the

telescope, a shattered man. One of his favourite dreams was of some nice,

eligible girl, belonging to a good family, and possessing a bit of money of

her own, coming along some day and taking Freddie off his hands; but that

inner voice, more confident now than ever, told him that this was not she.

Freddie would not sneak off in this furtive fashion to meet eligible girls,

nor could he imagine any eligible girl, in her right senses, rushing into

Freddie's arms in that enthusiastic way. No, there was only one explanation.

In the cloistral seclusion of Blandings, far from the Metropolis with all

its conveniences for that sort of thing, Freddie had managed to get himself

entangled. Seething with anguish and fury, Lord Emsworth hurried down the

stairs and out on to the terrace. Here he prowled like an elderly leopard

waiting for feeding-time, until in due season there was a flicker of white

among the trees that flanked the drive and a cheerful whistling announced

the culprit's approach.

It was with a sour and hostile eye that Lord Emsworth

watched his son draw near. He adjusted his pince-nez, and

with their assistance was able to perceive that a fatuous smile

of self-satisfaction illumined the young man's face, giving him

the appearance of a beaming sheep. In the young man's buttonhole

there shone a nosegay of simple meadow flowers, which, as

he walked, he patted from time to time with a loving hand.

'Frederick!' bellowed his lordship.

The villain of the piece halted abruptly. Sunk in a roseate

trance, he had not observed his father. But such was the sunniness

of his mood that even this encounter could not damp him.

He gambolled happily up.

'Hullo, guv'nor!' he carolled. He searched in his mind for a

pleasant topic of conversation – always a matter of some little

difficulty on these occasions. 'Lovely day, what?'

His lordship was not to be diverted into a discussion of the

weather. He drew a step nearer, looking like the man who

smothered the young princes in the Tower.

'Frederick,' he demanded, 'who was that girl?'

The Hon. Freddie started convulsively. He appeared to be

swallowing with difficulty something large and jagged.

'Girl?' he quavered. 'Girl? Girl, guv'nor?'

'That girl I saw you kissing ten minutes ago down in the

water-meadows.'

'Oh!' said the Hon. Freddie. He paused. 'Oh, ah!' He paused

again. 'Oh, ah, yes! I've been meaning to tell you about that,

guv'nor.'

'You have, have you?'

'All perfectly correct, you know. Oh, yes, indeed! All most

absolutely correct-o! Nothing fishy, I mean to say, or anything

like that. She's my

fiancée'

A sharp howl escaped Lord Emsworth, as if one of the bees

humming in the lavender-beds had taken time off to sting him

in the neck.

'Who is she?' he boomed. 'Who is this woman?'

'Her name's Donaldson.'

'Who is she?'

Aggie Donaldson. Aggie's short for Niagara. Her people

spent their honeymoon at the Falls, she tells me. She's American

and all that. Rummy names they give kids in America,' proceeded

Freddie, with hollow chattiness. 'I mean to say! Niagara!

I ask you!'

'Who is she?'

'She's most awfully bright, you know. Full of beans. You'll

love her.'

'Who is she?'

'And can play the saxophone.'

'Who,' demanded Lord Emsworth for the sixth time, 'is she?

And where did you meet her?'

Freddie coughed. The information, he perceived, could no

longer be withheld, and he was keenly alive to the fact that it

scarcely fell into the class of tidings of great joy.

'Well, as a matter of fact, guv'nor, she's a sort of cousin of

Angus McAllister's. She's come over to England for a visit, don't

you know, and is staying with the old boy. That's how I happened

to run across her.'

Lord Emsworth's eyes bulged and he gargled faintly. He had

had many unpleasant visions of his son's future, but they had

never included one of him walking down the aisle with a sort of

cousin of his head-gardener.

'Oh!' he said. 'Oh, indeed?'

'That's the strength of it, guv'nor.'

Lord Emsworth threw his arms up, as if calling on Heaven to

witness a good man's persecution, and shot off along the terrace

at a rapid trot. Having ranged the grounds for some minutes, he

ran his quarry to earth at the entrance to the yew alley.

The head-gardener turned at the sound of his footsteps.

He was a sturdy man of medium height, with eyebrows that

would have fitted a bigger forehead. These, added to a red

and wiry beard, gave him a formidable and uncompromising

expression. Honesty Angus McAllister's face had in full measure,

and also intelligence; but it was a bit short on sweetness and

light.

'McAllister,' said his lordship, plunging without preamble

into the matter of his discourse. 'That girl. You must send

her away.'

A look of bewilderment clouded such of Mr McAllister's

features as were not concealed behind his beard and eyebrows.

'Gurrul?'

'That girl who is staying with you. She must go!'

'Gae where?'

Lord Emsworth was not in the mood to be finicky about

details.

Anywhere,' he said. 'I won't have her here a day longer.'

'Why?' inquired Mr McAllister, who liked to thresh these

things out.

'Never mind why. You must send her away immediately.'

Mr McAllister mentioned an insuperable objection.

'She's payin' me twa poon' a week,' he said simply.

Lord Emsworth did not grind his teeth, for he was not given

to that form of displaying emotion; but he leaped some ten

inches into the air and dropped his pince-nez. And, though

normally a fair-minded and reasonable man, well aware that

modern earls must think twice before pulling the feudal stuff on

their

employés,

he took on the forthright truculence of a large

landowner of the early Norman period ticking off a serf.

'Listen, McAllister! Listen to me! Either you send that girl

away to-day or you can go yourself. I mean it!'

A curious expression came into Angus McAllister's face – always

excepting the occupied territories. It was the look of a

man who has not forgotten Bannockburn, a man conscious of

belonging to the country of William Wallace and Robert the

Bruce. He made Scotch noises at the back of his throat.

'Y'r lorrudsheep will accept ma notis,' he said, with formal

dignity.

'I'll pay you a month's wages in lieu of notice and you will

leave this afternoon,' retorted Lord Emsworth with spirit.

'Mphm!' said Mr McAllister.

Lord Emsworth left the battle-field with a feeling of pure

exhilaration, still in the grip of the animal fury of conflict. No

twinge of remorse did he feel at the thought that Angus McAllister

had served him faithfully for ten years. Nor did it cross his

mind that he might miss McAllister.

But that night, as he sat smoking his after-dinner cigarette,

Reason, so violently expelled, came stealing timidly back to her

throne, and a cold hand seemed suddenly placed upon his heart.

With Angus McAllister gone, how would the pumpkin fare?

The importance of this pumpkin in the Earl of Emsworth's

life requires, perhaps, a word of explanation. Every ancient

family in England has some little gap in its scroll of honour,

and that of Lord Emsworth was no exception. For generations

back his ancestors had been doing notable deeds; they had sent

out from Blandings Castle statesmen and warriors, governors

and leaders of the people: but they had not – in the opinion of

the present holder of the title – achieved a full hand. However

splendid the family record might appear at first sight, the fact

remained that no Earl of Emsworth had ever won a first prize for

pumpkins at the Shrewsbury Show. For roses, yes. For tulips,

true. For spring onions, granted. But not for pumpkins; and

Lord Emsworth felt it deeply.

For many a summer past he had been striving indefatigably to

remove this blot on the family escutcheon, only to see his hopes

go tumbling down. But this year at last victory had seemed in

sight, for there had been vouchsafed to Blandings a competitor

of such amazing parts that his lordship, who had watched it

grow practically from a pip, could not envisage failure. Surely, he

told himself as he gazed on its golden roundness, even Sir

Gregory Parsloe-Parsloe, of Matchingham Hall, winner for

three successive years, would never be able to produce anything

to challenge this superb vegetable.

And it was this supreme pumpkin whose welfare he feared he

had jeopardized by dismissing Angus McAllister. For Angus

was its official trainer. He understood the pumpkin. Indeed, in

his reserved Scottish way, he even seemed to love it. With Angus

gone, what would the harvest be?

Such were the meditations of Lord Emsworth as he reviewed

the position of affairs. And though, as the days went by, he tried

to tell himself that Angus McAllister was not the only man in

the world who understood pumpkins, and that he had every

confidence, the most complete and unswerving confidence, in

Robert Barker, recently Angus's second-in-command, now promoted

to the post of head-gardener and custodian of the Blandings

Hope, he knew that this was but shallow bravado. When

you are a pumpkin-owner with a big winner in your stable, you

judge men by hard standards, and every day it became plainer

that Robert Barker was only a makeshift. Within a week Lord

Emsworth was pining for Angus McAllister.