Blood and Guts (30 page)

Authors: Richard Hollingham

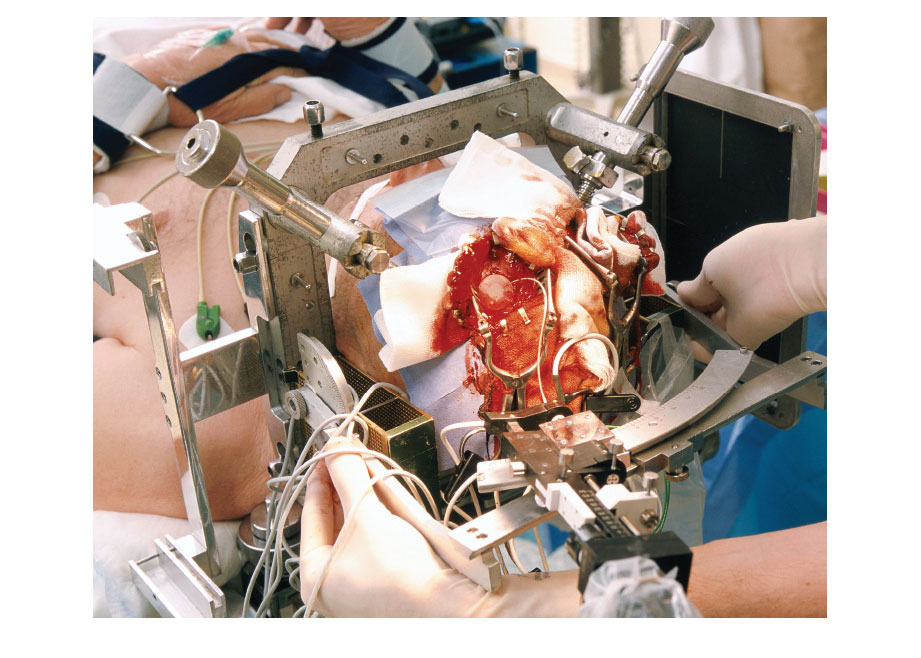

A modern operation for the treatment of Parkinson's

disease. The fearsome looking clamp is to hold the patient's

head in place so that surgeons can place implants precisely

in the affected area of the brain.

SURGERY

OF THE SOUL

THE MAN WHO SHOULD HAVE DIED

Vermont, 13 September 1848

The navvies said that Phineas Gage was the best foreman they'd ever

had. The twenty-five-year-old was fair and honest, a good worker and

a fine leader. He was employed on the Rutland & Burlington

Railroad. The promoters of the railroad hoped it would soon make

them rich: winding through the wooded hills of New England, it

would link Vermont to the cities of the east coast, bringing trade

and creating new markets for the state's agricultural and mineral

wealth. It was a fine enterprise indeed, and one well suited to an

industrious and practical worker such as Gage.

Gage's work gang had been toiling since early morning near the

town of Cavendish. They were building the roadbed – clearing and

levelling the land in preparation for the rails. The plans called for a

deep cutting, which had to be blasted through the granite hillside.

When it was finished, rock would dwarf the trains as they rounded

the sharp bend in the track. It would be a proud moment, thought

Gage, when the first steam engine – wheels pounding, head lamp

blazing – rolled along the track into town. For that to happen there

was still much work to do. Gage would make sure it was done, on

time and to the highest standards.

As foreman, Gage was highly skilled in the use of explosives, but

it was a tricky and dangerous job. First his men would drill a hole in

the rock – using a manual drill on solid granite was not an easy task.

Gage made sure that the hole was carefully positioned so that the

natural fractures in the rock could be used to maximize the effects

of the explosion. Next he lowered a measured amount of gunpowder

into the shaft and inserted a fuse. He tamped the powder gently

with his tamping iron before adding a layer of sand. The sand

helped confine the explosion to a small space, focusing the charge

into the rock rather than back up through the hole, which was

simply a waste of good gunpowder. Finally, Gage tamped the sand

good and hard, lit the fuse and stood well back. It was a job he did

every day.

Gage was so practised with explosives that he even had his own

custom-made tamping iron. The three foot seven inch-long iron bar

was an inch and a quarter in diameter. The bar was round, flat at

one end – the end he used to pack the explosives and sand – and

tapered to a point at the other. It was more than a crowbar; it was

styled almost like a javelin. A fine iron bar for an iron-willed man.

An unfortunate description given what was about to occur.

It was half past four. They were nearing the end of another hard

day and Gage could not wait to get back to the inn where he was

staying. Most of his men were looking forward to an evening drink,

but Gage rarely touched alcohol himself. They were loading lumps

of rock on to a flat car as Gage prepared to blast another section

from the hillside.

He lowers the string of the fuse into the hole and pours in the

gunpowder. He begins to tap the powder gently with his iron.

Distracted by the work going on behind him, he leans forward over

the hole. Perhaps he forgets that the sand hasn't yet been poured,

or perhaps he slips. But when he tamps the iron again, it goes in too

hard and catches on the granite. It ignites a spark.

The gunpowder explodes.

The iron rod shoots out of the hole like a bullet from a gun. It

goes straight through Gage's cheek, passes through the floor of his

left eye into the front of his brain and tears out of the top of his

head. His skull is splayed apart as the iron continues its journey

upwards, eventually returning to earth some eighty feet away,

smeared with blood and bits of brain. Some of Gage's brain is later

found splattered across the rocks where the rod landed.

*

*

The men who found the iron reported that it was 'covered with blood and brains'. They

washed it in a nearby brook, but it still had a 'greasy' appearance and was 'greasy to the touch'.

Gage was knocked on to his back by the force of the explosion.

His men ran across to find him twitching on the ground. A few

moments later he spoke. Then, to everyone's astonishment, he got

up and started to walk towards the road. He was helped on to an

ox cart and driven the three-quarters of a mile into the centre of

town. When he arrived at the tavern of Joseph Adams, where he

was lodging, he walked with only a little assistance and sat in a chair

on the veranda. He chatted with some of the men who gathered

around and answered questions about his injury. Gage had rarely

missed a day's work in his life and said he was keen to get back to

the railroad.

When Dr Edward Williams arrived at around five o'clock he

could not believe what he seeing. It made no sense – how could this

man possibly be alive? Gage remained perfectly lucid, insisting that

the bar did indeed pass right through his head. One of the labourers

corroborated the story: 'Sure it was so, sir, for the bar is lying in

the road below, all blood and brains.'

Despite the burn marks on Gage's cheek, the copious amounts

of blood dribbling down the poor man's face and the fragments of

bone sticking from his head, Williams was still unable to accept what

had happened. It wasn't until Gage started vomiting a large quantity

of blood and, as Williams noted, 'about half a teacupful of the brain,

which fell upon the floor' that the doctor finally came round to the

idea that Gage had survived the firing of an inch and a quarter-wide

tamping iron through his head.

Williams was completely flummoxed by the case, and seemed

reluctant to administer any treatment. So an hour later, when Dr

John Harlow arrived, Gage was still sitting on the veranda answering

questions and recounting his dramatic tale; also occasionally vomiting

blood, bone and lumps of brain that had dropped through the

hole from the top of his head into his mouth. Harlow was impressed

with how Gage 'bore his sufferings with the most heroic firmness'.

Despite becoming increasingly exhausted from the massive loss of

blood, Gage recognized the doctor at once and needed little assistance

to make his way up the stairs to his room.

Harlow was much more practical although, unsurprisingly,

somewhat taken aback by the mess. 'His person and the bed on

which he was laid were literally one gore of blood,' he recalled.

However, this didn't stop the doctor passing his fingers completely

through the hole. 'I passed in the index finger its whole length, without

the least resistance, in the direction of the wound in the cheek,

which received the other finger in like manner,' he later reported.

Together the doctors cleaned and dressed Gage's wounds. They

shaved his scalp and removed a few bits of bone and a stray piece of

brain that was 'hung by a pedicle', as well as bandaging the burns on

his hands and arms. Harlow pressed the jigsaw of bones on the top

of Gage's skull back into position as best he could and left the man

propped up in bed, where his bandages gradually became saturated

with blood. A couple of the men volunteered to watch over him.

When Harlow returned at seven the next morning, Gage was

still conscious. He had even managed to snatch some sleep during

the night. Harlow didn't expect him to live for much longer, and the

undertaker was called so that Gage could be measured for his coffin.

It seemed the prudent thing to do. As the undertaker took his measurements,

Gage's mother arrived to say her last goodbyes.

By 15 September Gage's condition had indeed deteriorated. He

was passing in and out of consciousness, he was delirious and incoherent.

On the 16th Harlow replaced the dressings but described 'a

fetid sero-purulent discharge, with particles of brain intermingled'.

That couldn't be good.

Harlow continued to visit his patient every day, and by the 22nd

it seemed that the stubborn (and iron-willed) Gage was finally ready

to die. He was hardly sleeping at all; he threw his arms and legs

about as if he was trying to get out of bed. His body was hot, his

wounds fetid. He even told the doctor, 'I shall not live long so.'

One month later Gage was walking up and down the stairs, even

into the street. His wounds were healing rapidly and he was eating

well. His bowels were described as 'regular' and he had even

stopped vomiting globules of brain. By the end of November all the

pain had subsided and Gage told the doctor that he was 'feeling

better in every respect'. He could walk, talk and eat. There was only

one problem: Gage was no longer Gage.

He described it as a 'queer feeling'. Others said the man had

completely changed. The accident had radically transformed his

personality. The railroad foreman who had once been described

as sober, patient and industrious was now vulgar, impatient and

impulsive. Gage was rude, they said, and could suddenly break forth

into vile profanity. When he reapplied for his position as foreman

his employers said the change in his mind was so marked that they

refused to take him on. He was described as childlike in his attitude,

but 'with the animal passions of a strong man'.

Gage's accident went beyond mere medical curiosity. When the

iron bar tore away part of his brain it revealed the inner workings of

the mind. It demonstrated that the brain is not some homogeneous

grey pudding, but is made up of different parts doing different

things. This is a concept known as localization, and would become

vitally important for our understanding of the brain and for the first

tentative advances in brain surgery.

Most of our personality, our sense of 'self', is contained behind

the forehead, in the frontal lobes of the brain. These were the parts

that were blasted away by Gage's tamping iron – the parts sprayed

on to the rock or those that he later vomited across the floor. The

frontal lobes are where we think and plan things. When the rod

ripped through Gage's brain it tore away his personality and made

him more impulsive. A century later surgeons would employ smaller

rods to do much the same thing.

Gage never did return to the railroad. With his tamping iron as

his constant companion, he travelled across New England. He eventually

ended up in New York, where for a while it is said he became

a sideshow in the famous Barnum's American Museum. For a few

cents, punters could see a living man with a hole in his head.

Although anyone expecting to see something truly gruesome would

have been sorely disappointed. They could see (and perhaps if they

were lucky, touch) the tamping iron, but the hole was now healed

and there was little to show for Gage's trauma. Instead visitors could

listen to Gage as he used another skull to regale his dramatic story.

In December 1848 Harlow's account of the case was printed in

the

Boston Medical and Surgical Journal

. It was greeted with scepticism

by the medical establishment, most of whom believed Gage's survival

to be completely impossible. Surely Harlow must be mistaken? What

would a rural doctor like Harlow know about the anatomy of the

brain anyway? However, by 1849 Gage's case had attracted the attention

of the new professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School,

Henry Jacob Bigelow, who compiled a detailed account of the accident

and paraded Gage (and his tamping iron) in front of surgical

colleagues, suggesting that this was 'the most remarkable history of

injury to the brain which has been recorded'. Thanks to Bigelow,

Gage's accident would become a medical sensation and one of the

most curious incidents in the whole history of surgery.

In the first days after the explosion it had been reported in the

local paper as merely a 'Horrible Accident'. Workers died all the

time on the railroad; it was hardly big news. But now, as more and

more newspapers heard about the case, Gage's fame spread. He

could have made a comfortable living on the medical freak show

circuit – travelling around the USA from circus to surgical symposium

(they often amounted to the same thing). He would be the

nineteenth-century equivalent of a daytime chat show guest.

However, Gage's new impulsive nature took him in a different

direction. The new Gage discovered that he enjoyed working with

animals and went to work at a livery stable. For a while he cared for

horses and drove a stagecoach in Chile. But with his health failing,

he returned to the United States in 1859, finding employment on a

farm in California. Then, in 1860, the accident that should have

killed him finally did.

In February 1860, while ploughing a field, he suffered an

epileptic fit. During these final few months of his life he started to

suffer more and more fits and convulsions. Doctors did the only

thing they knew how – which was to bleed him – but the treatment

seemed to have little effect. Phineas Gage finally died in May 1860,

twelve years after a three foot seven inch-long iron rod passed

through his brain.

Although Harlow's treatment of Gage was exemplary, it is one

thing to piece back together a fractured skull or even care for major

head injuries such as those sustained by Gage, but it is quite another

to open up the head and poke around in the brain – to have a crack

at brain surgery. As far as most surgeons were concerned, any

attempt to go further than repairing a head injury was to be avoided

at all costs. Anaesthetics, advances in anatomy and, later, Joseph

Lister's antiseptic operating techniques (see Chapter 1) might have

transformed nineteenth-century medicine, but the brain was still a

mystery, locked away in the sealed casket of the skull. Few surgeons

were prepared to open this casket, and those who did usually came

quickly to regret it. The only exception to the unwritten 'no operating

on the brain' rule was the ancient practice of trepanning.

Trepanning is arguably the world's oldest surgical practice –

although amputation is likely to run it a close second. It involves

drilling a hole, from half an inch to two inches across, into the skull.

The patient would have had their hair and skin scraped away before

the prehistoric equivalent of a surgeon started to bore into their

head with a sharpened stone or, later, a crude metal drill.