Authors: Alexandra J Churchill

Blood and Thunder (32 page)

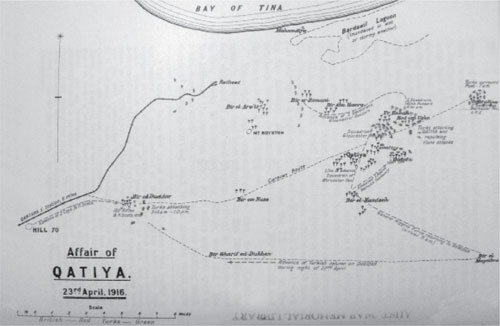

The Australians and New Zealanders who had been marked to take over the area arrived a few days later to find the wounded still strewn through the desert. All about the camp men and horses lay still dying whilst others half burrowed into the sand looking for shade. Heaps of spent cartridges lay next to the bodies; some of them garrotted and others bayonetted or tortured by the Bedouin. One trooper had been lying next to a wounded officer,;shot through the neck, he kept trying to speak, despite his injuries. Men were crawling through the sand, delirious and looking for water. The nights were so cold that they lay shivering and unable to sleep.

Scorgie lay in the sand for three days. All he could talk about when the Australian Light Horse found him was whisky and Ego. He kept telling them to look for Lord Elcho, that he might be alive and wounded elsewhere in the sand. âSearch, oh search everywhere. Please go and search until you find him.'

It was decided that Micky Quenington ought to be taken to lay beside his recently deceased wife. Men of the regiment acted as his pall-bearers and he was given a funeral in Cairo. Michael Lloyd-Baker was amongst the fallen; shot through the stomach he was much maligned for not withdrawing his force but, as Tom Strickland bore witness, his fellow OE had been expressly told to stay put and that help was on the way.

Tom had remained unscathed until the last five minutes when he got âa slight touch' on the elbow and a wound to the shoulder. The Turks were in a hurry to leave with their prisoners, edgy about a counter-attack. They refused to let Tom or his men get their overcoats from their tents, forcing them to line up in fours, including the walking wounded. A German colonel then appeared speaking English and removed their papers. He even commiserated with Tom when he saw a letter amongst his things saying that he was a couple of weeks away from a month's leave to England. Hungry, tired and scared about what would happen to them next they moved off.

The German officer was a âdecent sort of man'. He praised the Gloucesters for their courage and when he found out just how few of them that there had been âhe thumped his fist into his hand and said, âYou

have

put up a good fight!' Tom watched his colleagues hobbling pitifully along towards Beersheba. Unknowing British airmen dropped bombs on them to compound their misery, inflicting further damage on the wounded . They were marched along, day and night for hours at a time. The Mecca Camel Corps passed them, taunting them with fierce songs. Even their German leader admitted that he was afraid of being pushed aside with his Turks and that his bag of prisoners would be murdered.

The Countess of Wemyss, still mourning the very recent loss of Yvo at Loos, was of a spiritual nature. On the night before the Turkish attack, she recalled, she had had an odd nightmare at Stanway: âI felt the stress and the strain and saw, as if thrown on a magic lantern sheet, a confused mass of black smoke splashed with crimson flame; it was like a child's picture of the battle or explosion and in the middle of it I saw Ego standing.'

A few days later, before the Anzac troops had found the survivors at Qatiya, the family read that there had been a scrap east of the canal where the Gloucesters were known to be. News of Viscount Quenington's death arrived immediately but for the rest, there was a strange silence. Letty telegraphed from Egypt to say that Ego and Tom were both prisoners and that Ego had been slightly wounded, but that was all she knew, which was agonising for his wife who couldn't bear the thought that Ego was most likely being marched further and further away from her.

An officer from one of the other Gloucester squadrons went out to Qatiya to interrogate the Australian troops who had taken over the camp. He returned supremely confident that none of the bodies found could have been Ego. Letty was now ecstatic, for he would at least be safe until the end of the war. Mary too, frantic for news of her new husband Tom and of her brother, sought and was given permission to interview the wounded Gloucesters now lying in Egyptian hospitals. They also had the US Consul in Cairo wire the American embassy in Constantinople before she and Letty packed up and returned to England to be with the family. A few days after the officer returned from interviewing the Anzac men, a note arrived from Tom, merely telling her that he was alive. To Letty's utter despair it said nothing of his brother-in-law; his captors had forbidden it.

On 10 June the telephone rang when the countess was sitting in her husband's sitting room to say that the Red Cross had found Ego; that he was a prisoner of war and had ended up in Damascus. âWe were wild with joy.' Then, silence. No further information was forthcoming âand hope began to fade again'. Lord Wemyss repeatedly called at the American embassy, desperate for news, but then a telegram arrived from the Red Cross. It nullified their previous statement and confirmed that Ego was killed in the dying moments of the fight at Qatiya. Letty assumed a position of complete denial. Ego's eldest sister, Cynthia, rushed to her and together they survived âthat first dreadful night'. A padre with the Australian Light Horse came to tea and claimed to have found Ego with two volumes of Herodotus beside him and to have buried him himself. The Turks and the Arabs had stripped him of his clothes and he covered him with sand until they could go back and conduct a proper burial. It would be weeks before Tom could get a proper letter off. It was soon corroborated by the testimony of one of the troopers who wrote: âLord Elcho wounded twice then shell blew out his chest,

acted magnificently

.' âHe was killed instantaneously,' Tom was finally able to reveal. âMichael Baker was killed quite early on and Ego took command ⦠The men put up a splendid fight until an hour after he was killed, when ⦠[we] were surrounded and had to surrender.' Tom had watched as, when the Turks had approached to within 150 yards, a shell came careening towards the machine-gun post and burst exactly where he had seen Ego lying. When the smoke cleared, neither Ego nor the man that had been with him was anywhere to be seen. As the Turks had rounded up their prisoners Tom had gone to the spot, but Ego and all traces of his equipment had vanished. The Countess of Wemyss had now lost two sons in the space of six months. Ego's once reluctant servant, the gruff Scorgie, recovered from his wounds and answered her invitation to visit Stanway. When he arrived on her doorstep in Gloucestershire to talk to her about her eldest son's last hours he was in floods of tears.

Ego's grave was lost and he was commemorated on the Jerusalem Memorial along with 3,298 other men, including five more Etonians, all of whom were lost in the campaign in Sinai and Palestine before the end of the war. Patrick Shaw-Stewart never told Letty what he thought of Ego because he found it hard to articulate his feelings. âShe might perhaps not think it flattering.' But he thought that he was much like Charles Lister. âFools to the world and philosophers before God', neither had yet achieved great things in the conventional sense of the word. But perhaps they had the last laugh and knew what life was really all about. âThey formed, for me,' he wrote, âa little sect apart from the hustling, intriguing, lusting, coveting, money-loving herd of us.'

Notes

Â

1

Michael Hugh Hicks-Beach, Viscount Quenington.

Â

2

Captain George Robert Wiggin and Lieutenant Sir John Henry Jaffray. Neither man was recovered and both are commemorated on the Jerusalem Memorial.

12

At the onset of 1916 the BEF was some ten times bigger than the initial contingent that had been dispatched in August 1914. Regulars and territorials had been joined by a multitude of personnel, from New Army men to troops from all over the empire. At the end of 1915 a crucial change occurred. The failure at Loos was devastating and did not come without consequences. On 19 December 1915 Sir John French was removed from command and replaced by one of his subordinates, Douglas Haig.

Despite the large numbers of troops now at his disposal, like his predecessor, Haig was still expected to conform with the French command, which was of the opinion that the British should be shouldering more of the burden on the Western Front. Shortly before Haig assumed control a conference was held at which it was established that a joint AngloâFrench offensive would commence in summer 1916. Haig himself favoured a push in Flanders, where if it was successful they could eradicate the German presence from the Belgian coast, but General Joffre was insistent on another path. Planning began for an attack in Picardy at a point where the British and French lines met by the River Somme. For all the organisation now underway on the part of the Allies, the German Army was not idle. It had been making its own offensive preparations.

On 21 February 1916 the German Army launched a colossal assault on the fortress at Verdun which dragged France to the brink. Joffre's men suffered hundreds of thousands of casualties. By the time the Germans were finished, there was no way that the French were able to launch a full-on assault alongside the British on the Somme. In fact, it became more realistic to describe the assault as a British offensive to ease the pressure on the French further south.

The Germans had been digging themselves in on the Somme since 1914. The front line incorporated several fortified villages with names that would become synonymous with British hardship during the battle. The front line itself was actually a whole system of trenches and strongpoints that had been massively fortified with elaborate dugouts installed to protect their occupants. Behind this was another system and beyond that yet another had been begun so a formidable task lay before the Allied troops. To take up the task, Haig picked two subordinates, both OEs, to plan the offensive: 53-year-old Hubert Gough was the elder brother of âJohnnie', the Victoria Cross-winning Etonian general who had been so adamant that the Germans would not break through at Ypres in October 1914. Hubert had left Eton in 1888 and embarked on a cavalry career. It was curtailed by his threat of resignation during the Curragh incident of 1914 but he had been steadily climbing the ranks since the outbreak of war. In July 1916, in command of a reserve army, Gough would be waiting with his men to capitalise on the anticipated success. But the man charged with smashing through the German trench systems in the first place was his fellow Etonian, General Henry Seymour Rawlinson.

Rawlinson was born in 1864, the eldest son of a famous Assyriologist whose deciphering of ancient texts was only outdone by the translation of the Rosetta Stone. âRawley', as he was known to certain friends, arrived at Eton in 1878, high-spirited and good at games. He had a passion for horses inherited from his father and a corresponding one for art and sketching that came from his mother, whose family was descended from that of Jane Seymour, third wife of Henry VIII.

Rawlinson was placed in command of the Fourth Army, which was in fact a unit aimed at breaking up the administration of the now huge BEF rather than an independent organisation. By the time the summer offensive commenced he would have at his disposal some half-a-million men. Rawlinson was to lead the planning himself. He opted for caution. What he came up with was a series of stages to be executed with pauses to reposition the artillery for maximum effectiveness. All of this was based not only on his own tours of the area but on experience honed throughout the war so far.

Unfortunately Haig threw it out straight away as a soppy effort to kill a few Germans and gain a bit of ground. He wanted much, much more; namely the first and second German trench systems taken in one swoop with a diversion further north chucked in. He wanted to smash the enemy and overrun them. Haig was relentless, but Rawlinson did not challenge him sufficiently and so Haig got his way. Rawlinson's huge force would be responsible for a main assault whilst men of another army attacked at Gommecourt, further north. Rawlinson's half a million men, along with over a thousand guns, would try to decisively break the Germans north of the River Somme. The preparations were elaborate and the Germans watched huge numbers of troops and masses of equipment arriving on the front in the weeks running up to the opening day of the attack, knowing that all of it was about to be thrown at them.

Hugh, Guy and Harry Cholmeley were the three surviving sons of a solicitor from St John's Wood. Following the loss of two baby boys both named Robert, Hugh was born in 1888, Guy followed in 1889 and Harry, the youngest, was born in 1893. All three boys passed through Mr Somerville's house at Eton. Hugh arrived in 1901 but suffered from rather severe asthma. Forbidden from taking part in games he indulged his passion for music instead. Instead of university, their parents sent him off travelling to try to improve his constitution. He returned to London to be articled to the family firm where he was due to be made a partner when war was declared.

His brother followed a different path. On leaving Eton in 1908 Guy followed the century-old Cholmeley tradition of going up to Magdalen College, Oxford, where their father had been a contemporary of Oscar Wilde. Whilst studying architecture he joined a number of young men at the college who had joined up as territorials in the London Rifle Brigade. His despatch to the front, therefore, was swift and Guy arrived in Flanders in November 1914.