Blood Land (27 page)

LIVING WHERE you can see to what feels like the ends of the earth always filled Pruett with peace. He never could have survived in a jungle made of concrete—no easier, anyway, than he tolerated the jungles of Vietnam, where a man sometimes couldn’t see past the end of his rifle. But in Wyoming, where the prairies still stretched out infinitely before a man, save for a small group of pronghorns he could feel as the Crow and the Blackfoot and the Sioux must have felt—as if men really did own the entirety of the Earth.

And Pruett knew, as the Native Americans knew—as his friend, Malcolm Whitefeather, who saved them all knew—when you owned something, you also owed it something. You owed it many things, actually, but respect perhaps more than anything. And Pruett respected the land. The land wasn’t a vault for the greedy but a place for a person to build and live and grow, in harmony, with respect.

“I love you, Dad,” Wendy Steele said as they sat side-by-side, leaning against the rails of the small Pruett cemetery where mother and wife Bethy rested—maybe in peace at last; now that the wrongs had been righted some.

His daughter’s words—hearing them after all these years—almost made everything all right for Sheriff Pruett, too. In fact the words

did

make everything all right, at least for the moment, and Pruett was content to live there, in the now, and not to worry too hard on what might be coming next.

The mess the BLM and the McIntyre family laid out across the town of Wind River and the county of Sublette itself was grime that wouldn’t be cleaned from the walls for some time, if ever. There was a poetic irony to the ending of the legalities, however: though patriarch Will McIntyre never considered a woman—namely his granddaughter, Bethy—worthy of part or parcel when it came to family land and fortune, the probate court ruled that Cort’s criminal conspiracy to obtain more than his share put him not only in prison but also in forfeiture of his part of the fortune. The court ruled to split the mineral royalties due on all McIntyre lands between the only two honest heirs, Bethy and Ty.

Bethy’s share then went accordingly to her next living heir, Wendy.

Ty would be challenged not to drink away his small fortune, though he now had an entire ranch to run with no family and but a few rough hands to work for him.

Pruett never knew before but would now never forget that a true hangman’s knot contains no fewer than thirteen coils, with the executioner placing the knot directly behind the left ear of the condemned. The design was meant to break the victim’s neck, not strangulate him, which would be cruel and unusual. The young agent who manufactured

Ty’s

noose made a simple slipknot, which would have still been more than effective at choking the life from the man.

When Pruett saw Ty step from the table at the Townsley cabin and the rope go stiff, he looked down to the ground and saw his revolver lying at his feet, where Warren had dropped it after murdering Honey McIntyre. The sheriff dropped to one knee, scooped up his sidearm, aimed at the highest point on the rope above Ty’s head, let out half a breath to steady himself, and carefully squeezed off one round.

The bullet did not sever the rope but

did

split it in half—Ty’s one hundred and seventy pounds was then enough to finish the job and the half-unconscious cowpoke dropped to the ground, breaking both ankles in the process.

Wendy and her father then hurried to where he lay, removed the rope, and verified the man’s pulse and ragged but steady breathing.

“How’s your uncle, Wendy?”

“You still haven’t visited him?” she said.

Pruett shook his head and gazed off into the heavens. “Too hard. Too many mixed emotions still,” he said. “Once a heart gives in fully to grieving, it’s a process I guess. I’ll be up to it one of these days.”

“He’s doing all right,” Wendy said. “He’s still drinking. But I think he’s beginning to take to the idea that the McIntyre ranch and name are his to carry on.”

“Like I said before, he ain’t half bad.”

Wendy pushed in closer to her father’s side. “We’re heading back to Laramie in the morning.”

“You and the professor.”

“Mm-hmm.”

“No wedding bells yet? You wouldn’t elope and rob me of a chance to walk you down the aisle now would you, girl?”

“Not yet. And no. When I walk down the aisle it’ll be with the man I love most in the world by my side.”

And in

that

moment Pruett just knew he could never feel happier again.

http://bit.ly/rsguthrie

First, you don’t write a novel about Wyoming and not acknowledge the genuine, unique, hard-working, tough-loving people of the land itself. I have many friends there still, both American and Native American. The latter know how I feel about history, but every one of you has a pride that no one will ever be able to take away. I depict the ranchers in a way I had to for the story. I admire what you all do. There is one quote I repeat here, because it’s the truest thing in rural Wyoming:

They might tolerate you, even befriend you—but it was a closed society.

I say that with the deepest respect. You are the toughest, hardest-working men and women I’ve ever had the pleasure of knowing.

The Bull Rider’s Prayer is not mine, and I dedicate it to Eb Richie, who may not read this book but whom I

did

see one evening in the town drugstore years after high school and his face looked just as I described it. That night, the bull had won.

To my editor, Russell Rowland, an acclaimed, published writer in his own right: you did me a solid and, as always, you made my words better with each and every suggestion. You are also the best I know at also providing the positive “nice” where earned.

To my proofreader, Becky Illson-Skinner, you are as talented as you are lovely and no book should ever go out without coming under an eye as studious as your own.

To my main beta reader, friend, and confidant Gail Gentry—whose forthcoming novel will undoubtedly show the world yet another crazy talent from the Indie world—words don’t express my gratitude for everything you’ve done.

To my wife, Amy, who has read Dark Prairies more times in full and in part than any other living human being, thank you for believing in me but most for believing in this book as much as I do. I love you.

To bestselling author and friend, Russell Blake. Wild man. Scary man. Great writer. Without your help, I know I would not be on the road I am now. I’m not sure how I will ever thank you. Indebted forever, mi amigo.

And to the readers. Without you, we authors are without audience. Please remember, the most profound, life-altering gift you can offer the writer you love is to tell as many avid readers as you are able. We exist and succeed only as long you bring others into the fold.

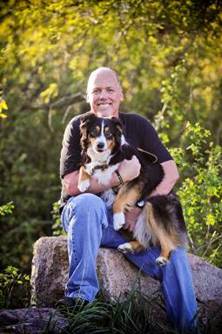

R.S. Guthrie lives in Colorado with his beautiful wife, three Australian Shepherds, and a Chihuahua who believes she’s a forty-pound Aussie. The Guthrie dogs are their children and there is no disputing the fact that the canines rule the household.

The second in the

James Pruett Mystery

series,

Money Land

is available now. The third,

Honor Land

, is currently in the works.

The author’s next planned book is the third in the

Detective Bobby Mac Thriller

series, entitled

Reckoning

. Somewhere in the near future, however, there is a dog book digging to get out, and it will pay homage to the kindest, most loyal animals on the planet.

Pictured with the author is three year-old Elsa. She is as intelligent and as beautiful as she appears (and knows it all too well.)

You can learn more about R.S. Guthrie and his books on his website

http://www.rsguthrie.com

or on his blog “Rob on Writing” at

http://robonwriting.com

AVAILABLE NOW