Blood on the Tracks: A History of Railway Crime in Britain (28 page)

Read Blood on the Tracks: A History of Railway Crime in Britain Online

Authors: David Brandon,Alan Brooke

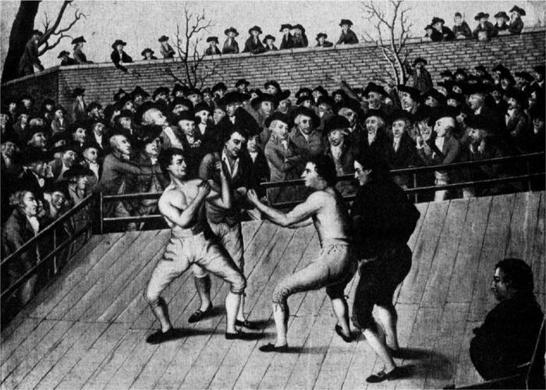

A bare-knuckle boxing bout in the eighteenth century. Pugilism still attracted large crowds in the nineteenth, and when it was banned some railway companies put on clandestine specials. The fights were staged deep in the country and the arrangements kept secret until the last possible minute.

T

he British took a long time to be won to the idea of a professional police force. This was because of concerns that such a force would intrude not only into criminal activities but also into the private and political aspects of people’s lives as it was widely believed occurred with such forces in France, for example. However, the development of large-scale industrialisation in Britain was accompanied by interrelated processes involving a rapid expansion in the size of the economy, significant population growth and urbanisation.

One result was an increase in the opportunities for criminal activity, especially among the volatile population of the rapidly growing towns. Much of the growing population consisted of people who had migrated from elsewhere on the mainland or from Ireland and they frequently lacked the social and familial ties of the long-established communities from which they had come. They also tended to lack deference to such traditional sources of authority as the big local landowner or the established Church.

For several generations society in the developing towns and cities was in a state of considerable turmoil as a response to the immense tensions created by the twin processes of industrialisation and urbanisation. Although statistics relating to the eighteenth century are very incomplete, it is clear that there was a considerable increase in all sorts of crime and that the existing, largely amateur, methods of maintaining law and order were incapable of keeping this increase under control.

Nowhere was this more true than London and it was in the metropolis that the progenitors of modern professional policing can be found. The famous Bow Street Runners had been set up in 1750 and they were largely paid only

when their activity led to the successful prosecution of wrong-doers. In this sense they were bounty-hunters or thief-takers. Such men had a long history in Britain. Various mounted and foot patrols were established over the next decades, also under the control of the Bow Street magistrates.

The Pool of London, with its vast amounts of shipping and enormous diversity of valuable cargoes in the holds of ships or on neighbouring quaysides and in warehouses, attracted thieves like moths to a flame, and the result was that tens of millions of pounds worth of goods went missing annually. In an attempt to stem this flow the Thames River Police were formed by an Act of Parliament in 1800. This was a regular professional police force. Similar but far better known were the Metropolitan Police who were established by law in 1829 as a result of the continuing efforts of the then Home Secretary, Sir Robert Peel. The success of the ‘Bobbies’ or ‘Peelers’ led to the creation of similar forces elsewhere over the next decades, and it was not long before the establishment of such constabularies became mandatory in England and Wales.

The first railway company to employ men in a police role was the Stockton & Darlington which opened in 1825. Their brief was to guard the railway and its associated activities against theft and other crime, to patrol as a visible deterrent to potential criminal activity and to contribute to the safe working of the line. They were full-time paid employees and were dressed distinctively in a uniform of a non-military style.

The more significant Liverpool & Manchester Railway opened in 1830 and had a police force with similar duties, except that additionally they acted as the predecessors of signalmen – or signallers as they are now called. It was this role, in combination with their uniforms which were modelled on those of the Metropolitan Police, that led to railway workers using the word ‘Bobby’ to refer to signalmen. The early railway policemen only had powers of arrest on railway property itself and were frequently left impotently cursing their ill luck when a suspect was sufficiently fleet of foot to evade their clutches and escape onto adjoining land.

In 1838 railway companies were required by law to provide their own police forces instead of drawing on local constabularies. This had been something which ratepayers strongly resented because they did not see why they should subsidise the security needs of private companies. The boisterous and sometimes illegal activities of the railway navvies have been discussed elsewhere, but they required a lot of policing and local forces had often been called upon to keep order, the numbers of railway company police often being insufficient to cope with outbreaks of trouble.

A number of towns, of which Crewe, Swindon and Wolverton are examples, were virtually created by the railways and were company towns in that sense. There the railway police in the early days carried out the functions of

the county constabulary where such a force existed. One by one the railway companies established their own police forces and the men concerned were faced with an intimidating set of duties. Let us take the regulations of the Great Western Railway as an example.

Apart from the overall requirement that the police officers be vigilant and watch over and preserve law and order on railway property, they had to receive and despatch signals, operate points and crossings, ensure there were no obstructions on the line, assist in the event of accidents, remove trespassers, patrol lines and installations to ensure that all the company workers were carrying out their duties satisfactorily, announce arrivals and departures, provide help and information for people requiring assistance, watch for such possibilities as land slips or bridge failures, make safety checks on the rails and sleepers and ensure that their superior officers were kept fully up-to-date with all developments and incidents.

When required they were expected to carry passengers’ luggage and check tickets. In return for this they received a wage, in most cases unlikely to exceed one pound for a six-day week. Fortunately this range of duties gradually became curtailed as they tended to be taken over by specialist workers and the officers were able to concentrate on what Gilbert and Sullivan described as constabulary duties. Oh yes, they were also expected to salute passing trains!

Another aspect of railway policing was detective work and, of course, you’ve guessed it, as if the poor old railway bobby was not busy enough already he was expected to do a spot of detecting as well. However, it was not long before specialist detectives began to be used. They worked in plain clothes and were often disguised as porters or similar staff and they worked inconspicuously on stations and in goods depots where thefts were regularly taking place.

Perhaps a more interesting job was following and watching people who had made large claims for compensation from a railway company for personal injuries supposedly sustained on or around railway property. It was by no means unknown for such people to obtain the necessary medical certification and yet to be seen striding purposefully – and with a look of eager greedy anticipation – towards the courtroom where their case was about to be considered. They did not always have the sense to slow down and start limping when they came in sight of the court!

One example of such a fraudster was a passenger aboard a train of the London & North Western Railway which received a slight bump during a shunting operation at Euston station. It really was only the slightest jolt and no one else bothered except this particular gentleman, who claimed that he had not only had an awful shock but he had also injured his back so severely that he was unable to carry on his lucrative private business. He demanded compensation. It was quickly discovered that the man had no business at all but was in serious debt and had chanced on the incident at Euston as a way of raising much-needed cash.

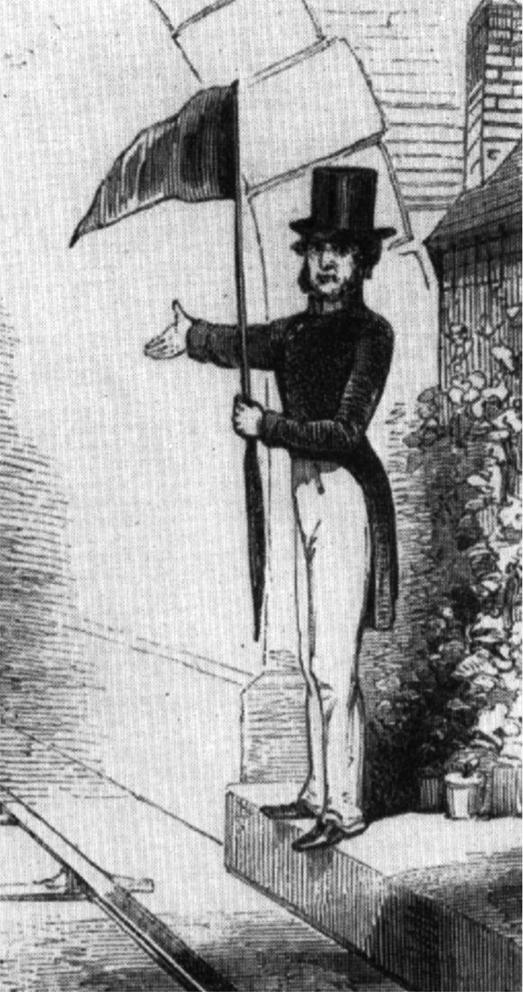

A railway policeman indicating the ‘All Clear’. His general appearance is like the Metropolitan Police established around 1829 by Sir Robert Peel.

He was trailed for several weeks by railway detectives who watched him as he heaved great pieces of furniture and heavy trunks and boxes around when helping a lady friend to move home. He was also seen romping energetically on the floor with the lady’s infant son. His case against the company was summarily dismissed by the court and the London & North Western Railway then took out a warrant for perjury. Our friend had managed to scrape together sufficient money for a ticket to the USA but he was arrested shortly before he was due to embark. His reward was nine months’ hard labour.

Perhaps typical of the thousand and one seemingly mundane cases dealt with by the railway detectives was one which came to court at Birmingham in 1917. In the dock was James Hardwick, a shunter in the employment of the Great Western Railway and he was accused of having stolen half a pint of essence of lemonade to the value of one shilling from a box van at Hockley Goods Depot in the city. Two Great Western Railway detectives were on the

night shift at the depot and heard someone moving around in the van. They squatted down and awaited developments.

It was Hardwick in the van and he was apprehended carrying a drinking can containing lemonade, which he said he had been using to put under a leaking container of the drink. There was indeed a large stone jar containing essence of lemonade in the van but it was not leaking. There were also containers of whisky and the court took the somewhat uncharitable view that Hardwick, and perhaps others, were helping themselves to the odd whisky and lemonade to make the night shift a little more tolerable.

Hardwick was fined but managed to avoid a custodial sentence. It is likely that he also lost his job. A very different incident occurred in the 1900s at what was then Cardiff general station. There a Great Western Railway detective intervened in the nick of time to prevent a dastardly Frenchman eloping with an eighteen-year-old Welsh girl described as being ‘of exceedingly attractive appearance’.

Sometimes the activities of the railway police provided a bit of knockabout farce. Early in the 1980s plain-clothes officers were investigating a series of ingenious thefts of mail bags from railway property at Basingstoke. They kept watch on the platform and, to their surprise, saw what looked like a clerical gentleman making off with a number of mail bags. They gave chase and apprehended the man only to be set upon in turn by two robust elderly ladies who belaboured the officers with their umbrellas, convinced that the clergyman was being assaulted by cowardly thugs. The ‘clerical gentleman’ turned out to be a professional actor between jobs whose brief criminal career around Basingstoke station had garnered him about

£

100,000 of stolen mail.

In the 1980s the police, including British Transport Police, were aware that a very dangerous vagrant was at large, with a string of convictions for drink-related offences and who had previously been tried and acquitted on a murder and attempted murder charge. He had confessed to an officer that he had killed at least nine people and attacked innumerable others, his victims always fellow vagrants for whom he had enormous contempt.