Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin (32 page)

Read Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin Online

Authors: Timothy Snyder

Tags: #History, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #European History, #Europe; Eastern - History - 1918-1945, #Political, #Holocaust; Jewish (1939-1945), #World War; 1939-1945 - Atrocities, #Europe, #Eastern, #Soviet Union - History - 1917-1936, #Germany, #Soviet Union, #Genocide - Europe; Eastern - History - 20th century, #Russia & the Former Soviet Union, #Holocaust, #Massacres, #Genocide, #Military, #Europe; Eastern, #World War II, #Hitler; Adolf, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Massacres - Europe; Eastern - History - 20th century, #World War; 1939-1945, #20th Century, #Germany - History - 1933-1945, #Stalin; Joseph

Hermann Göring, at this time Hitler’s most important associate, held overall responsibility for economic planning. His Four-Year-Plan Authority had been charged with preparing the German economy for war between 1936 and 1940. Now his Four-Year-Plan Authority, entrusted with the Hunger Plan, was to meet and reverse Stalin’s Five-Year Plan. The Stalinist Five-Year Plan would be imitated in its ambition (to complete a revolution), exploited in its attainment (the collective farm), but reversed in its goals (the defense and industrialization of the Soviet Union). The Hunger Plan foresaw the restoration of a preindustrial Soviet Union, with far fewer people, little industry, and no large cities. The forward motion of the Wehrmacht would be a journey backward in time. National Socialism was to dam the advance of Stalinism, and then reverse the course of its great historical river.

Starvation and colonization were German policy: discussed, agreed, formulated, distributed, and understood. The framework of the Hunger Plan was established by March 1941. An appropriate set of “Economic Policy Guidelines” was issued in May. A somewhat sanitized version, known as the “Green Folder,” was circulated in one thousand copies to German officials that June. Just before the invasion, both Himmler and Göring were overseeing important aspects of the postwar planning: Himmler the long-term racial colony of Generalplan Ost, Göring the short-term starvation and destruction of the Hunger Plan. German intentions were to fight a war of destruction that would transform eastern Europe into an exterminatory agrarian colony. Hitler meant to undo all the work of Stalin. Socialism in one country would be supplanted by socialism for the German race. Such were the plans.

16

Germany did have an alternative, at least in the opinion of its Japanese ally. Thirteen months after the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact had alienated Tokyo from Berlin, German-Japanese relations were reestablished on the basis of a military alliance. On 27 September 1940, Tokyo, Berlin, and Rome signed a Tripartite Pact. At this point in time, when the central conflict in the European war was the air battle between the Royal Air Force and the Luftwaffe, Japan hoped that this alliance might be directed at Great Britain. Tokyo urged upon the Germans an entirely different revolution in world political economy than the one German planners envisioned. Rather than colonizing the Soviet Union, thought the Japanese, Nazi Germany should join with Japan and defeat the British Empire.

The Japanese, building their empire outward from islands, understood the sea as the method of expansion. It was in the interest of Japan to persuade the Germans that the British were the main common enemy, since such agreement would aid the Japanese to conquer British (and Dutch) colonies in the Pacific. Yet the Japanese did have a vision on offer to the Germans, one that was broader than their own immediate need for the mineral resources from British and Dutch possessions. There was a grand strategy. Rather than engage the Soviet Union, the Germans should move south, drive the British from the Near East, and meet the Japanese somewhere in South Asia, perhaps India. If the Germans and the Japanese controlled the Suez Canal and the Indian Ocean, went Tokyo’s case, British naval power would cease to be a factor. Germany and Japan would then become the two world powers.

17

Hitler showed no interest in this alternative. The Germans told the Soviets about the Tripartite Pact, but Hitler never had any intention of allowing the Soviets to join. Japan would have liked to see a German-Japanese-Soviet coalition against Great Britain, but this was never a possibility. Hitler had already made up his mind to invade the Soviet Union. Though Japan and Italy were now Germany’s allies, Hitler did not include them in his major martial ambition. He assumed that the Germans could and should defeat the Soviets themselves. The German alliance with Japan would remain limited by underlying disagreements about goals and enemies. The Japanese needed to defeat the British, and eventually the Americans, to become a dominant naval empire in the Pacific. The Germans needed to destroy the Soviet Union to become a massive land empire in Europe, and thus to rival the British and the Americans at some later stage.

18

Japan had been seeking a neutrality pact with the Soviet Union since summer 1940; one was signed in April 1941. Chiune Sugihara, the Soviet specialist among Japanese spies, spent that spring in Königsberg, the German city in East Prussia on the Baltic Sea, trying to guess the date of the German invasion of the Soviet Union. Accompanied by Polish assistants, he made journeys through eastern Germany, including the lands that Germany had seized from Poland. His estimation, based upon observations of German troop movements, was mid-June 1941. His reports to Tokyo were just one of thousands of indications, sent by intelligence staffs in Europe and around the world, that the Germans would break the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and invade their ally in late spring or early summer.

19

Stalin himself received more than a hundred such indications, but chose to ignore them. His own strategy was always to encourage the Germans to fight wars in the west, in the hope that the capitalist powers would thus exhaust themselves, leaving the Soviets to collect the fallen fruit of a prone Europe. Hitler had won his battles in western Europe (against Norway, Denmark, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and France) too quickly and too easily for Stalin’s taste. Yet he seemed unable to believe that Hitler would abandon the offensive against Great Britain, the enemy of both Nazi and Soviet ambitions, the one world power on the planet. He expected war with Germany, but not in 1941. He told himself and others that the warnings of an imminent German attack were British propaganda, designed to divide Berlin and Moscow despite their manifest common interests.

Apart from anything else, Stalin could not believe that the Germans would attack without winter gear, which none of the espionage reports seemed to mention.

20

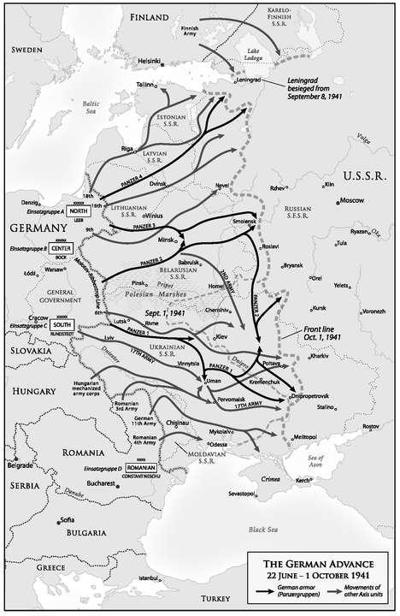

That was the greatest miscalculation of Stalin’s career. The German surprise attack on the Soviet Union of 22 June 1941 looked at first like a striking success. Three million German troops, in three Army Groups, crossed over the Molotov-Ribbentrop line and moved into the Baltics, Belarus, and Ukraine, aiming to take Leningrad, Moscow, and the Caucasus. The Germans were joined in the invasion by their allies Finland, Romania, Hungary, Italy, and Slovakia, and by a division of Spanish and a regiment of Croatian volunteers. This was the largest offensive in the history of warfare; nevertheless, unlike the invasion of Poland, it came only from one side, and would lead to war on one (very long) front. Hitler had not arranged with his Japanese ally a joint attack on the Soviet Union. Japan’s leaders might have decided to attack the USSR on their own initiative, but instead decided not to break the neutrality pact. A few Japanese leaders, including Foreign Minister Yōsuke Matsuoka, had urged an invasion of Soviet Siberia. But they had been overruled. On 24 June 1941, two days after German troops had entered the Soviet Union, the Japanese army and navy chiefs had adopted a resolution “not to intervene in the German-Soviet war for the time being.” In August, Japan and the Soviet Union reaffirmed their neutrality pact.

21

German officers had every confidence that they could defeat the Red Army quickly. Success in Poland, and above all in France, had made many of them believers in Hitler’s military genius. The invasion of the Soviet Union, led by armor, was to bring a “lightning victory” within nine to twelve weeks. With the military triumph would come the collapse of the Soviet political order and access to Soviet foodstuffs and oil. German commanders spoke of the Soviet Union as a “house of cards” or as a “giant with feet of clay.” Hitler expected that the campaign would last no more than three months, probably less. It would be “child’s play.” That was the greatest miscalculation of Hitler’s career.

22

Ruthlessness is not the same thing as efficiency, and German planning was too bloodthirsty to be really practical. The Wehrmacht could not implement the Hunger Plan. The problem was not one of ethics or law. The troops had been relieved by Hitler from any duty to obey the laws of war toward civilians, and German soldiers did not hesitate to kill unarmed people. They behaved in the first days of the attack much as they had in Poland. By the second day of the invasion, German troops were using civilians as human shields. As in Poland, German soldiers often treated Soviet soldiers as partisans to be shot upon capture, and killed Soviet soldiers who were trying to surrender. Women in uniform, no rarity in the Red Army, were initially killed just because they were female. The problem for the Germans was rather that the systematic starvation of a large civilian population is an inherently difficult undertaking. It is much easier to conquer territory than to redistribute calories.

23

Eight years before, it had taken a strong Soviet state to starve Soviet Ukraine. Stalin had put to use logistical and social resources that no invading army could hope to muster: an experienced and knowledgeable state police, a party with roots in the countryside, and throngs of ideologically motivated volunteers. Under his rule, people in Soviet Ukraine (and elsewhere) stooped over their own bulging bellies to harvest a few sheaves of wheat that they were not allowed to eat. Perhaps more terrifying still is that they did so under the watchful eye of numerous state and party officials, often people from the very same regions. The authors of the Hunger Plan assumed that the collective farm could be exploited to control grain supplies and starve a far larger number of people, even as Soviet state power was destroyed. The idea that any form of economic management would work better under Soviet than German control was perhaps unthinkable to the Nazis. If so, German efficiency was an ideological assumption rather than a reality.

24