Read Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin Online

Authors: Timothy Snyder

Tags: #History, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #European History, #Europe; Eastern - History - 1918-1945, #Political, #Holocaust; Jewish (1939-1945), #World War; 1939-1945 - Atrocities, #Europe, #Eastern, #Soviet Union - History - 1917-1936, #Germany, #Soviet Union, #Genocide - Europe; Eastern - History - 20th century, #Russia & the Former Soviet Union, #Holocaust, #Massacres, #Genocide, #Military, #Europe; Eastern, #World War II, #Hitler; Adolf, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Massacres - Europe; Eastern - History - 20th century, #World War; 1939-1945, #20th Century, #Germany - History - 1933-1945, #Stalin; Joseph

Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin (40 page)

The city of Łódź fell within the domain of Arthur Greiser, who headed the Wartheland, the largest district of Polish territory added to the Reich. Łódź had been the second-most populous Jewish city in Poland, and was now the most populous Jewish city in the Reich. Its ghetto was overcrowded before the arrival of the German Jews. It could be that the need to remove Jews from Łódź inspired Greiser, or the SS and Security Police commanders of the Wartheland, to seek a more efficient method of murder. The Wartheland had always been at the center of the policy of “strengthening Germandom.” Hundreds of thousands of Poles had been deported beginning in 1939, to be replaced by hundreds of thousands of Germans who arrived from the Soviet Union (before the German invasion of the USSR made shipping Germans westward utterly pointless). But the removal of the Jews, always a central element of the plan to make this new German zone racially German, had proven the hardest to implement. Greiser confronted a problem on the scale of his district that Hitler confronted on the scale of his empire: the Final Solution was officially deportation, but there was nowhere to send the Jews. By early December 1941 a gas van was parked at Chełmno.

46

Hitler’s deportation of German Jews in October 1941 smacked of improvisation at the top and uncertainty below. German Jews sent to Minsk and Łódź were not themselves killed but, rather, placed in the ghettos. The German Jews sent to Kaunas were however killed upon arrival, as were those of the first transport sent to Riga. Whatever Hitler’s intentions, German Jews were now being shot. Perhaps Hitler had decided by this point to murder all of the Jews of Europe, including German Jews; if so, even Himmler had not yet grasped his intention. It was Jeckeln who killed the German Jews arriving in Riga, whom Himmler had

not

wished to murder.

Himmler did set in motion, also in October 1941, a search for a new and more effective way of killing Jews. He made contact with his client Odilo Globocnik, the SS and Police Leader for the Lublin district of the General Government, who immediately set to work on a new type of facility for the killing of Jews at a site known as Bełżec. By November 1941 the concept was not entirely clear and machinery was not yet in place, but certain outlines of Hitler’s final version of the Final Solution were visible. In the occupied Soviet Union, Jews were being killed by bullets on an industrial scale. In annexed and occupied Poland (in the Wartheland and in the General Government), gassing facilities were under construction (at Chełmno and Bełżec). In Germany, Jews were being sent to the east, where some of them had already been killed.

47

The Final Solution as mass murder, initiated east of the Molotov-Ribbentrop line, was spreading to the west.

In November 1941 Army Group Center was pushing toward Moscow, to win the delayed, but no less glorious, final victory: the end of the Soviet system, the beginning of the apocalyptic transformation of blighted Soviet lands into a proud German frontier empire. In fact, German soldiers were heading into a much more conventional apocalypse. Their trucks and tanks were slowed by the autumn mud, their bodies by the lack of proper clothing and warm food. At one point German officers could see the spires of the Kremlin through their binoculars, but they would never reach the Soviet capital. Their men were at the very limits of their supplies and their endurance. The resistance of the Red Army was ever firmer, its tactics ever more intelligent.

48

On 24 November 1941 Stalin ordered his strategic reserves from the Soviet East into battle against Army Group Center of the Wehrmacht. He was confident that he could take this risk. From a highly placed informer in Tokyo, and no doubt from other sources, Stalin had reports that there would be no Japanese attack on Soviet Siberia. He had refused to believe in a German attack in summer 1941 and was wrong; now he refused to believe in a Japanese attack in autumn 1941 and was right. He had kept his nerve. On 5 December the Red Army went on the offensive at Moscow. German soldiers tasted defeat. Their exhausted horses could not move their equipment back quickly enough. The troops would spend the winter outside, huddling in the cold, short on everything.

49

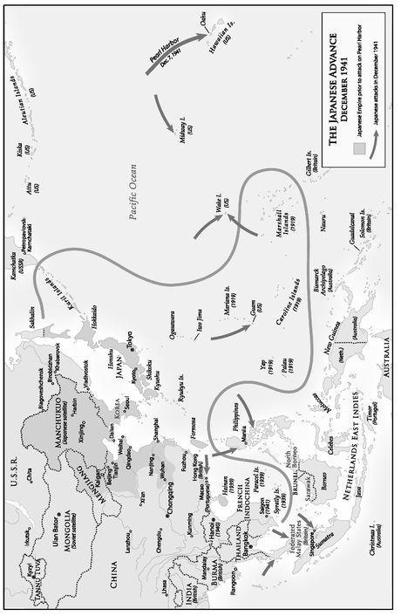

Stalin’s intelligence was correct. Japan was about to commit decisively to a war in the Pacific, which would all but exclude any Japanese offensive in Siberia. The southern course of Japanese imperialism had been set by 1937. It had been clear to all when Japan invaded French Indochina in September 1940. Hitler had discouraged his Japanese ally from joining in the invasion of the Soviet Union; now, as that invasion had failed, Japanese forces were moving further in the other direction.

Even as the Red Army marched west on 6 December 1941, a Japanese task force of aircraft carriers was sailing toward Pearl Harbor, the base of the United States Pacific Fleet. On 7 December, a German general, in a letter home, described the battles around Moscow. He and his men were “fighting for our own naked lives, daily and hourly, against an enemy who in all respects is superior.” That same day, two waves of Japanese aircraft attacked the American fleet, destroying several battleships and killing two thousand servicemen. The following day the United States declared war on Japan. Three days later, on 11 December, Nazi Germany declared war on the United States. This made it very easy for President Franklin D. Roosevelt to declare war on Germany.

50

Stalin’s position in east Asia was now rather good. If the Japanese meant to fight the United States for control of the Pacific, it was all but inconceivable that they would confront the Soviets in Siberia. Stalin no longer had to fear a two-front war. What was more, the Japanese attack was bound to bring the United States into the war—as an ally of the Soviet Union. By early 1942 the Americans had already engaged the Japanese in the Pacific. Soon American supply ships would reach Soviet Pacific ports, unhindered by Japanese submarines—since the Japanese were neutral in the Soviet-German war. A Red Army taking American supplies from the east was an entirely different foe than a Red Army concerned about a Japanese attack from the east. Stalin just had to exploit American aid, and encourage the Americans to open a second front in Europe. Then the Germans would be encircled, and the Soviet victory certain.

Since 1933, Japan had been the great multiplier in the gambles that Hitler and Stalin took with and against each other. Both men, each for his own reasons, wished for Japan to fight its wars in the south, against China on land and the European empires and the United States at sea. Hitler welcomed the bombing of Pearl Harbor, believing that the United States would be slow to arm and would fight in the Pacific rather than in Europe. Even

after

the failure of Operations Barbarossa and Typhoon, Hitler wished for the Japanese to engage the United States rather than the Soviet Union. Hitler seemed to believe that he could conquer the USSR in early 1942 and then engage an America weakened by the Pacific War. Stalin, too, wished for the Japanese to move south, and had very carefully crafted foreign and military policy that had precisely this effect. His thought was in essence the same as Hitler’s: the Japanese are to stay away, because the lands of the Soviet Union are mine. Berlin and Moscow both wanted to keep Japan in east Asia and in the Pacific, and Tokyo obliged them both. Whom this would serve depended upon the outcome of the German attack on the Soviet Union.

51

Had the German invasion proceeded as envisioned, as a lightning victory that leveled the great Soviet cities and yielded Ukrainian food and Caucasian oil, the Japanese strike on Pearl Harbor might indeed have been good news for Berlin. In such a scenario, the attack on Pearl Harbor would have meant that the Japanese were diverting the United States as Germany consolidated a victorious position in its new colony. The Germans would have initiated Generalplan Ost or some variant, seeking to become a great land empire self-sufficient in food and oil and capable of defending themselves against a naval blockade by the United Kingdom and an amphibious assault by the United States. This had always been a fantasy scenario, but it had some light purchase upon reality so long as German troops were making for Moscow.

Since the Germans were turned back at Moscow at the very moment that the Japanese advanced, Pearl Harbor had exactly the opposite meaning. It meant that Germany was in the worst of all possible configurations: not a giant land empire intimidating Great Britain and preparing itself for a confrontation with the United States but rather a single European country at war against the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States with allies either weak (Italy, Hungary, Romania, Slovakia) or uninvolved in the crucial east European theater (Japan, Bulgaria). The Japanese seemed to understand this better than the Germans. They wanted Hitler to make a separate peace with Stalin, and then fight the British and the Americans for control of Asia and North Africa. The Japanese wished to break Britain’s naval power; the Germans tried to work within its bounds. This left Hitler with one world strategy, and he kept to it: the destruction of the Soviet Union and the creation of a land empire on its ruins.

52

In December 1941, Hitler found a strange resolution to his drastic strategic predicament. He himself had told his generals that “all continental problems” had to be resolved by the end of 1941 so that Germany could prepare for a global conflict with the United Kingdom and the United States. Instead Germany found itself facing the timeless strategic nightmare, the two-front war, to be fought against three great powers. With characteristic audacity and political agility, Hitler recast the situation in terms that were consistent with Nazi anti-Semitism, if not with the original planning for the war. What besides utopian planning, inept calculation, racist arrogance, and foolish brinksmanship could have brought Germany into a war with the United Kingdom, the United States, and the Soviet Union? Hitler had the answer: a worldwide Jewish conspiracy.

53

In January 1939, Hitler had made a speech threatening the Jews with extinction if they succeeded in fomenting another world war. Since summer 1941, German propaganda had played unceasingly on the theme of a tentacular Jewish plot, uniting the British, the Soviets, and ever more the Americans. On 12 December 1941, a week after the Soviet counterattack at Moscow, four days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and one day after the United States reciprocated the German declaration of war, Hitler returned to that speech. He referred to it as a prophecy that would have to be fulfilled. “The world war is here,” he told some fifty trusted comrades on 12 December 1941; “the annihilation of Jewry must be the necessary consequence.” From that point forward his most important subordinates understood their task: to kill all Jews wherever possible. Hans Frank, the head of the General Government, conveyed the policy in Warsaw a few days later: “Gentlemen, I must ask you to rid yourselves of all feeling of pity. We must annihilate the Jews wherever we find them, in order to maintain the structure of the Reich as a whole.”

54