Bloody Mary (32 page)

Authors: Carolly Erickson

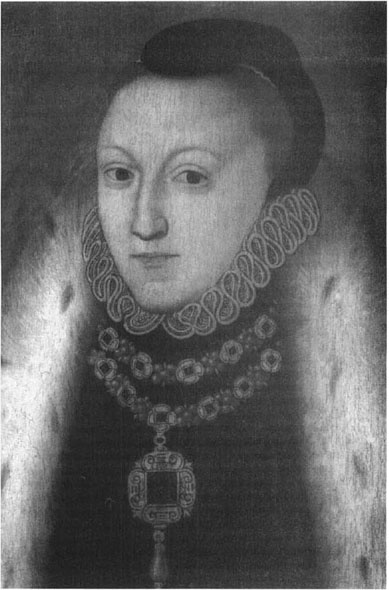

7. Elizabeth Tudor, ca. 1560. Artist unknown.

NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY, LONDON.

8a. Elizabeth I, coronation portrait. Artist unknown.

NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY, LONDON.

8b. Elizabeth I by Nicholas Hilliard, 1572.

NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY, LONDON.

9. Mary, Queen of Scots, ca. 1578. Artist unknown.

NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY, LONDON.

10a. Jane Seymour.

REPRODUCED BY GRACIOUS PERMISSION OF HER MAJEST

10b. Henry VIII, portrait attributed to Joos van Cleeve, conventionally dated 1536.

NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY, LONDON.

It had been difficult enough for Henry to hold the country together in the face of these forces of disunity. He had done it by retaining an image of serene mastery, by finding temporary ways around each successive wave of the continuing crisis, and when all else failed, by prompt and terrifying displays of force. Through it all he had remained awesome. No rebellion succeeded in robbing him of his power. But it was evident from 1547 on that neither Edward nor his uncle had the prestige to remain aloof from the unrest that was closing in around them. Popular loyalty-was eroding under intolerable economic and social pressures. “What weapons can pacify or keep quiet the hungry multitude?” the author of an anonymous treatise asked the Protector. “What faith and allegiance will those men observe towards their prince and governor which have their children famished at home for want of meat?”

3

In this atmosphere of fear and insecurity suspicion fell heavily on Mary. Writing to William Cecil about the risings Sir Thomas Smith, secretary of state, referred to “the Marian faction” in the population as if it posed an even greater threat than the rebels of the west and north. “As for the Marians, the matter torments me greatly, or rather, it nearly terrifies me to death,” he wrote. “Pray God of his mercy averts this evil from us.”

4

He had good reason to be afraid, for though she remained aloof from the political struggles in the Council Mary was taking on an increasingly important public role.

To English Catholics Mary was becoming a popular symbol of resistance to religious innovation. As the religious policies of the Council were transforming the official faith she made her adherence to the old faith as obvious as possible. Where before she had heard the customary one daily mass she now heard two or even three or four, and had prayers in her chapel every night.

5

When she went north to see the estates that had been assigned to her in Norfolk in the summer of 1548 the predominantly Catholic population gave her an enthusiastic welcome, and she made a display of her devout practices everywhere she went. “Whenever she had power to do it she had mass celebrated and the services of the church performed according to the ancient institution,” Van der Delft reported to the emperor.

6

It was almost certainly this public defiance of the religion of the king and Council that led members of the government to meet with Mary on her return. What they said to one another we don’t know, but Mary’s

popularity in the north was very much on the minds of the Council members when the men and women of Norfolk rose in revolt the following summer. The rebellion was in no sense a religious protest; Ket’s camp on Mousehold Heath followed the new English communion service and the rebels’ grievances were focused on their economic survival. Mary was back in the north when the revolt broke out, and she saw clearly that it had no confessional flavor. “All the rising about the parts where she was,” she said, “was touching no part of religion.”

7

If proof were needed that Mary had nothing to do with promoting the rebellion, it could easily have been supplied. The rebels did protest on her behalf that she was “kept too poor for one of her rank,” but they treated her fences as roughly as those of any other landlord, pulling down the enclosure of her park and tramping through her lands.

8

What no one in the government could have seen clearly as yet was that Mary was undergoing profound inner changes to accommodate the public role she felt herself called upon to play. She had always been predisposed to see life in monumental terms; now Catholicism and Protestantism became the huge polarities that overshadowed and drew to themselves every act and event in her experience. Her Catholic faith became much more to Mary than the dear belief of her childhood, the faith of the emperor and the regent, the church that had sustained her mother and for which so many of those she cherished had died. It was becoming the cause to which she devoted her being—as absolute and unyielding a commitment as that she had felt toward her mother’s cause long before.

Mary had always been a faithful Catholic. But what took shape within her now was so fundamental a merging of her self with her faith that it transcended religious devotion. It was a virtually complete identification of her personality and her destiny with the cause of Catholicism. Many years before Chapuys had urged Mary to save her life by giving in to her father and signing the Submission. He argued that in doing so she would be preserving herself to fulfill a higher destiny. Now that destiny was beginning to become clear. It would somehow be linked to her unswerving allegiance to the old faith, and to her emerging role as representative of all English Catholics.

The process was a slow one. It began when the remaining vestiges of Catholicism in England came under attack in 1547; it would not be complete until Mary herself took power. But signs of the transition were apparent from the first months of Edward’s reign, and by the spring of 1549 she saw clearly that she would soon come under pressure to abandon her faith and conform to the usages in Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer—the form of service whose introduction in June of that year led to the western rebellion. When Van der Delft saw Mary on March 30 she

confided to him how apprehensive she was about the consequences of her defiance. Her public manner was dignified, confident and determined; in private she felt vulnerable, anxious, increasingly concerned about the welfare of the country. To the ambassador she “complained bitterly of the changes brought about in the kingdom, and of her private distress, saying she would rather give up her life than her religion.”

Open conflict with the Council could not be avoided for long. When it came, she said, the emperor would be her only defender. This was true enough, though it is hard to believe Mary was entirely sincere when she told Van der Delft that “her life and her salvation” were in Charles’ keeping. She knew well enough that an attitude of helpless entreaty was what her imperial cousin expected of her, just as her father had, and exaggerated her desperation accordingly. But though Mary was no longer the terrified girl who had looked to the emperor almost as a savior in the 1530s, she still clung to the memory of what he and his sister had meant to her in those traumatic years. She showed the ambassador faded letters they had written to her at the time of her submission more than twelve years earlier. The letters were among her most cherished possessions, she said, and she took constant pleasure in them.

9

Charles was unmoved by Mary’s sentimental gesture in keeping his letters, but he was concerned about her situation all the same. Her status as heir apparent gave her more political importance than ever, and the possibility that, through Mary, he might bring England within the Haps-burg fold was never far from the emperor’s mind. He had been hearing conflicting rumors about her safety. It was said in Flanders that Thomas Seymour’s rash invasion of the king’s bedchamber had been meant as only the first step in a much vaster plot to kill Edward and Mary both.

10

In France it was being said that Mary herself uncovered the plot.

11

And in England, Paget was alleging that “it was plain in every respect” that the admiral intended to assassinate Edward and his sisters, and that he had long since recommended putting Mary in the Tower.

That such a conspiracy could be divised and attempted from within the government Charles found distressing, especially as he had other grounds for complaint against the regime as well. Corruption in the policing of the seas, in the collection of customs duties and in the treatment of foreign merchants had been straining relations between England and the empire for some time. When Thomas Seymour’s goods were searched after his arrest it was found he had amassed a huge treasure in the purloined property of Flemish merchants—his share in the plunder of the pirates who were his confederates. Seymour’s successor as admiral, Lord Clinton, continued to ally himself with the privateers and to heap up riches from Flemish ships; when accused by the aggrieved foreigners he

pretended ignorance. No justice was available to Flemish seamen in the Admiralty Court, and the fees charged by customs officials were twice what the law prescribed.