Blue Angel (11 page)

Authors: Donald Spoto

As an American millionairess, with Hans Albers in

Zwei Krawatten

: Berlin, 1929.

With director Josef von Sternberg, on the set of

The Blue Angel

: Berlin, December 1929.

As Lola Lola in

The Blue Angel

.

Departing from Berlin for Hollywood: April 1930.

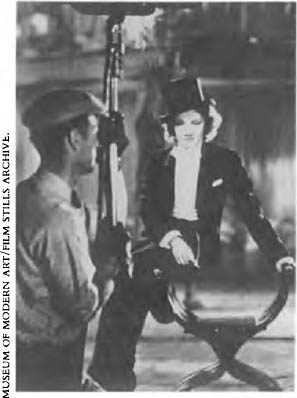

On the set of

Morocco

, 1930.

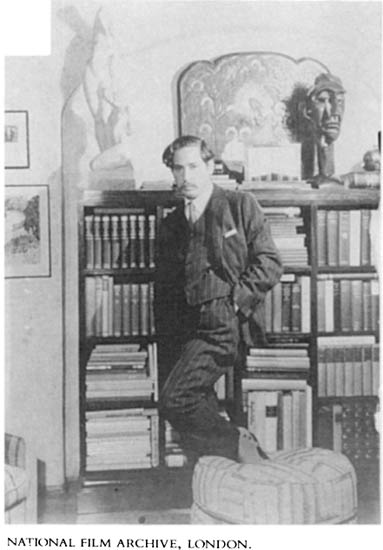

Von Sternberg at home in California, about 1930.

The critics, however, were not entertained. Alfred Kerr, Ludwig Sternaux and Franz Leppmann complained that she did too little, that she was simply showing off her lovely legs instead of any real dramatic ability—an objection again levelled at her in her next job, another Robert Land comedy—

Ich Küsse ihre Hand, Madame

(

I Kiss Your Hand, Madame

)—filmed in late 1928. In this romantic comedy she played a rich Parisian divorcée named Laurence Gérard, in love with a headwaiter who turns out to be a Russian count down on his luck. When Laurence’s overly attentive and obese lawyer (played by an actor aptly named Karl Huszar-Puffy) offers to do “anything in the world” for her, she replies, “All right, you can take my dogs for a walk.” The moment—as Dietrich scarcely glances at the hapless fellow through half-closed eyes—is both cruel and comic.

The beginning of 1929 found her still in film studios, this time in

Die Frau, nach der man sich sehnt

(

The Woman One Longs For

, released in America as

Three Loves

), cast as a sophisticate who is the mistress of her husband’s murderer and then falls in love with a third man, eventually getting herself killed in the bargain. Director Kurt Bernhardt (later successful in America as Curtis Bernhardt) had seen her in

Misalliance

and fought, against the producers, to have her play the leading role. This he later regretted, finding her difficult on two counts. First, “Marlene waged intrigues—one man against another” in life as in the story, he recalled. Exploiting the infatuation of her co-star, Fritz Kortner, she fueled petty disagreements between him and Bernhardt, the better to advance her own favor in the eyes of both. “She is an

intrigante

,” according to the director, who added in plain language that Dietrich “was a real bitch.”

This angry assessment was due to the second difficulty she caused Bernhardt:

She was so aware of her face that she would not let herself be photographed in profile because her nose turned up somewhat. She drove Kortner crazy (although he would have loved to go to bed with her). She never moved her head from the spotlight over the camera, facing forward and refusing to move her head to speak with other actors—she simply looked at them out of the corner of her eye. I wanted her to turn to Kortner, to be natural with him, but she wouldn’t do it. She was completely aware of the lighting and how it hit her nose. Marlene looked fantastic, but as an actress she was the punishment of God.

*

Her insistence had an odd payoff, for with her austere languor and apparently affectless gaze there were more comparisons than ever to Greta Garbo. “Directors have to get her out of this Garbo mimicking!” the critic of the

Berliner Tageblatt

had cried on January 20, 1929 (after the first screening of her preceding film); now, the

Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung

(on May 4) said of her latest performance that she was merely “a Garbo double in her somnambulist attitude and heavy-lidded gazes—as if she were exhausted in her playful laziness.” On May 22,

Variety

’s Berlin correspondent concurred in virtually identical words, and at once the Berlin representatives of at least two Hollywood studios—Paramount and Universal—cabled home to report a new international star. MGM had the real Garbo; would a reasonable facsimile be acceptable? To find and engage such a copy these men were paid handsome salaries. (When the picture was finally released in America that autumn, the

New York Times

hailed her “rare Garboesque beauty.”)

Two more films followed in rapid succession that spring and summer. In

Das Schiff der verlorenen Menschen

(

The Ship of Lost Men

), she was an American aviatrix who is rescued by a shipful of lusty thugs when her plane goes down in the Atlantic. Guided by the French director Maurice Tourneur, Dietrich (plumply attractive even though made up to be windblown and grimy in unflattering male garb) had little to do but rouse fever among the beasts. After

this—perhaps because she was still occasionally spending an evening with her old flame Willi Forst—she joined him in

Gefahren der Brautzeit

(

Dangers of the Engagement Period

), playing a sweet girl seduced by a friend of her fiancé.

In the sixteen silent films she had made in six years, Marlene Dietrich’s leading roles had been few, and these were in films that caused no great sensation. The same was true of her eleven Berlin stage appearances (and two in Vienna), so that if her name was dropped in acting circles in mid-1929, no great echo resounded.

On the other hand, despite her appearances as a calmly detached supporting player, she had a reputation among actors who knew her as a woman of untamed energies who led a tempestuous love life unfettered by her married state. Friends could not quite keep up with her romantic escapades, for she quite openly had serial (and sometimes simultaneous) liaisons with colleagues like Willi Forst and Claire Waldoff.

F

ROM HER NEXT ROLE, HOWEVER, WOULD COME AN

association that would forever change her life and destiny as well as the history of twentieth-century film.

On September 5, 1929, a nine-scene music and dance revue called

Zwei Krawatten

(

Two Neckties

) opened at the Berliner Theater, with text by Georg Kaiser and music by Mischa Spoliansky. In this comic satire about a waiter (Hans Albers) who changes his black tie for white tie and tails (and becomes a gentleman) Dietrich was cast in the minor role of an American millionairess named Mabel who had but one line of dialogue: “May I invite you all to dine with me this evening?” Otherwise she stood with a composed but sensual allure (“plump but agile, with a smoky voice and droopy eyelids,” reported one critic).

During the first week of performances that September, there was an especially observant spectator in the audience. He was scouring Berlin’s theaters looking for a singing actress for a film he was preparing.

Zwei Krawatten

was a logical stop, for it featured two players he had already signed for smaller roles. On hearing Dietrich’s one line and watching her lean against the scenery “with a cold disdain

for the buffoonery,” he stood up and left the auditorium—but not until he had found her name on the program. “Here was the face I had sought,” he later wrote, “and, so far as I could tell, a figure that did justice to it. Moreover, there was something else I had not sought, something that told me that my search was over.”

The director was Josef von Sternberg. Marlene Dietrich never worked again as a stage actress.

*

During all this, Dietrich was rumored to be romantically linked with Igo Sym and with the actor-playwright Hans Jaray. Although there is no evidence to support the talk of these affairs, her complicated (and well-documented) love life at the height of her international fame suggests that the delicate management of simultaneous liaisons was well within her competence.

*

One young flame, the architect Max Perl, later recalled that during the summer of 1929 she finally decided to correct the shape of her nose and submitted to the discomfort of cosmetic surgery; in this she was something of a hardy trailblazer, for such procedures were not the commonplace they later became.

5: 1929–1930

“I

FEEL AS IF

I

DIED IN

H

OLLYWOOD AND HAVE

now awakened in heaven,” said director Josef von Sternberg without obvious irony. It was August 16, 1929, and he had just arrived in Berlin to work on the preparations for his new motion picture, a German-American co-production and one of Europe’s first sound films. Greeting the assembled press amid the opulence of the Hotel Esplanade’s grand foyer, von Sternberg—then a thirty-five-year-old of lively intelligence and multiple talents—was looking forward to working in Germany for the first time. He was surrounded that afternoon by producer Erich Pommer; the star of the film, Emil Jannings; writer Carl Zuckmayer; cameramen Günther Rittau and Hans Schneeberger; and composer Friedrich Holländer.

Born in Vienna as Josef Sternberg, he had had a gruellingly destitute life, even after arriving in America in 1901 at the age of seven. Years of severe malnutrition had stunted his growth (his full

adult height was only five feet four inches) but not his agile mind. Denied formal education by the need to work, he read widely and in adolescence began to amass an impressive library of books on anthropology, comparative culture studies, psychology, art history, mythology and erotica. By the age of twenty-five he had held a variety of factory jobs and had served in the United States Signal Corps during the World War. He then decided to go to Los Angeles, where an earlier experience in an East Coast film laboratory prepared him for work as an editor, writer and assistant director. Among the pictures he worked on in 1923 was a trifle called

By Divine Right

, whose producers—impressed by the names of other Europeans in Hollywood (Erich von Stroheim, for example)—added an aristocratic-sounding

von

to his name—“without my knowledge and without consulting me,” as he later insisted in his autobiography. Unlike von Stroheim, however, he spoke English without any trace of a foreigner’s accent.